In the Border States of Maryland, Delaware, Kentucky, and Missouri the process of emancipation and enlisting formerly enslaved men played out under unique circumstances. Unlike the seceded slaveholding states, those who remained loyal to the Union and claimed ownership of the enslaved eligible for United States service believed they deserved compensation for their loss in human property. Some received payment if they could prove their allegiance. It appears that enslaved man John Grinnell fell under Maryland’s enrollment act and thus left bondage under his enslaver, William J. Edelen, Sr. of St. Mary’s County. Due to his military service, Grinnell experienced the sweet taste of liberty, if only for a brief time.

John Grinnell enlisted at Leonardtown, St. Mary’s County, on March 1, 1864. Less than a week later he officially mustered into United States service at Norfolk, Virginia. St. Mary’s County sent hundreds of men into the ranks of the United States Colored Troops. Two St. Mary’s County men, William H. Barnes and James H. Harris, both 38th USCI comrades of Grinnell, received the Medal of Honor for their valor at the Battle of New Market Heights. In addition, another 38th soldier, Edward Ratcliff, a Virginian, also received the honor.

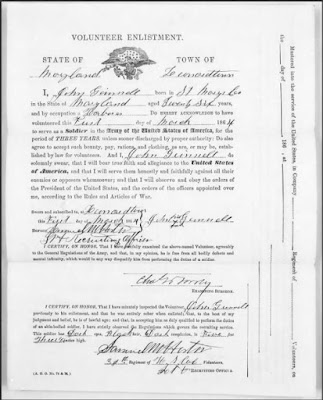

|

| John Grinnell's enlistment form |

Records indicate that John Grinnell was a native of St. Mary’s County, 26 years old, five feet three inches tall, and possessed a “dark” complexion. In less than two months after signing up, Grinnell received promotion to sergeant. By the time of Grinnell’s enlistment, he was a family man. John married Jane Lee on Christmas Eve, 1862. The couple’s union produced a daughter named Emily (Emma), who arrived on November 1, 1863.

It is unknown if William Edelen, Sr. also enslaved Jane Lee, or if she and John Grinnell endured an abroad marriage, which was not uncommon. William Edelen, Sr. appears in the 1860 census for District 3 of St. Mary’s County, as a physician and farmer of considerable wealth. Edelen’s family consisted of his wife Ellen and their seven children ranging in age from 22 to three. Much of Edelen’s $49,000 in personal property was due to his claiming 57 human laborers, who lived in five slave dwellings. Two of Edelen’s sons, Philip F. (1st Battery, Maryland Artillery), and William, Jr. (2nd Maryland Infantry Battalion) served in the Confederate army. Ironically, both soldier sons lost their freedom for time while confined at Point Lookout prison in their native St. Mary’s County.

The 38th USCI initially trained and served in the Norfolk, Portsmouth, and northeastern North Carolina area. However, as operations heated up around Petersburg and Richmond in the summer of 1864, the regiment transferred and eventually became part of the 3rd Division of the XVIII Corps. Despite being an eight-company regiment, the 38th soon proved they were more than worthy of joining Col. Alonzo Draper’s brigade, which also included the 5th USCI, recruited primarily in Ohio, and the 36th USCI, recruited in northeastern North Carolina and southeastern Virginia.

Located at Deep Bottom landing on the James River by the night of September 28, the 38th USCI and their brigade comrades moved out before daylight to a staging area where they formed and then awaited orders. After receiving a word of encouragement from Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler, who encouraged the men to “Remember Fort Pillow!,” Draper’s Brigade went to ground while Col. Samuel Duncan’s small brigade, consisting of the 4th USCI and 6th USCIs, attacked the Confederate earthworks along New Market Road. Duncan’s Brigade received devastating fire from along the Confederate front held in large part by the famous Texas Brigade. Unable to completely break the defensive line, and reeling after taking over 50 percent casualties, Duncan’s Brigade, or what was left of it, fell back to reorganize.

Col. Alonzo Draper’s Brigade received orders to attack next. Division commander, Brig. Gen. Charles J. Paine, ordered that Draper’s Brigade attack in column with the 5th USCI leading, followed by the 36th USCI, and finally the 38th USCI. Like Duncan’s Brigade, the 5th USCI met extremely heavy fire from the Confederates. During the time between the assaults, the Southerners had come out in front of their earthworks and collected the rifles of the killed and wounded in Duncan’s Brigade for Confederate use. While assaulting, the 5th and the rest of Draper’s Brigade halted at a line of abatis. After a pause, a cheer by the surviving officers and non-commissioned officers rallied the momentum of the brigade who surged through the abatis, up to and then over the earthworks, driving out the defenders.

Although Sgt. Grinnell’s regiment was last to attack, they sustained significant casualties. The horrific tally was 21 killed in action, 12 fatally wounded, and 75 surviving wounded. Those who fell killed in the fight included John Grinnell. In Gen. Butler’s October 11, 1864 report, the commander of the Army of the James commended Grinnell’s 38th USCI comrades Ratcliff, Barnes, and Harris, as well as white Sgt. Maj. Martin Weiss, and commissioned officers Lt. Samuel Bancroft, and Capt. Peter Schlick. Sgt. Grinnell went unmentioned, and thus, unfortunately, largely forgotten to the history of the Battle of New Market Heights.

|

| Three of Sgt. Grinnell's 38th USCI comrades received the Medal of Honor for valor at New Market Heights. Courtesy of the Smithsonian Institute. |

Jane Grinnell appears in the historical record immediately following the Civil War. It is unknown if she relocated to Norfolk, Virginia, during the war or afterward, but pension and Freedman’s Bureau records show her and Emily living there at Taylor’s Farm and having an account with the Freeman’s Bank. However, mother and daughter were not located in the 1870 census or records thereafter.

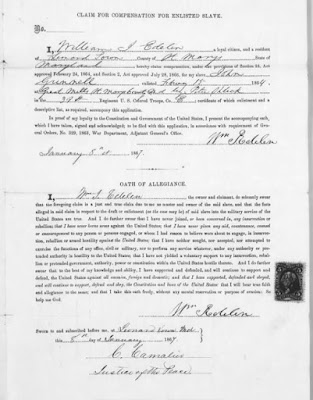

William Edelen, Sr. filed a compensation claim in 1867 for the loss of John Grinnell to the United States army three years earlier. In it Edelen swore he maintained loyalty throughout the war and that he never gave “any aid, countenance, counsel or encouragement to any person or persons engaged . . . in insurrection, rebellion or armed hostility against the United States,” despite having two sons in the Confederate army. Edelen also had two fellow citizens vouch for his war-time allegiance. Nothing in Sgt. Grinnell’s service records positively indicates that Edelen received compensation, but chances are good that he did. Had Sgt. Grinnell lived he probably would not have cared one way or the other. Ultimately, he broke his bonds of slavery by enlisting, and his service helped abolish slavery for others forever.

William Edelen's compensation claim for John Grinnell

The location of Sgt. Grinnell’s grave is unknown. His remains may be among those unknown soldiers reinterred at Fort Harrison National Cemetery or at City Point National Cemetery. Regardless of Grinnell’s ultimate resting place, we honor his courage in making the attack at New Market Heights, and we remember his sacrifice in service to the United States and for the causes of citizenship, liberty, justice, and Union.