Monday, May 30, 2011

Thursday, May 26, 2011

Kentuckian Richard T. Jacob at Cooper Union

Most students of the Civil War are aware of Lincoln's emergence as a viable Republican candidate for the presidential nomination after his appearance and speech at New York City's Cooper Union Institute in February 1860. But, I am sure fewer people are cognizant of the irony in that a fervid call was made for a change in administrations in the same building just four years later.

Most students of the Civil War are aware of Lincoln's emergence as a viable Republican candidate for the presidential nomination after his appearance and speech at New York City's Cooper Union Institute in February 1860. But, I am sure fewer people are cognizant of the irony in that a fervid call was made for a change in administrations in the same building just four years later.Sunday, May 22, 2011

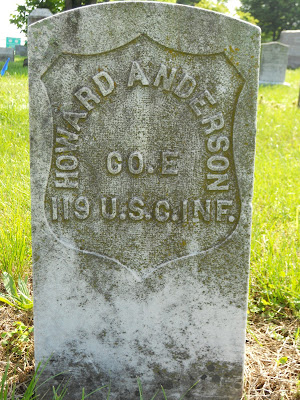

A Sunday Stroll in Frankfort's Greenhill Cemetery

Saturday, May 21, 2011

Shouldn't an Editor Catch These?

Reading as much as I do I often come across references in books that I know are incorrect. It is a pet peeve of mine to see errors, especially when they are in books published by some of the most reputable printers of scholarly works.

Reading as much as I do I often come across references in books that I know are incorrect. It is a pet peeve of mine to see errors, especially when they are in books published by some of the most reputable printers of scholarly works.Monday, May 16, 2011

A Kentucky Union Soldier in January 1863

Writing to his sister Jennie on January 15, 1863, while aboard the steamboat War Eagle, on the Mississippi River, Kentucky Union soldier John T. Harrington provided some interesting opinions on the Confederates that were his supposed enemies and his service in Mr. Lincoln's army.

Writing to his sister Jennie on January 15, 1863, while aboard the steamboat War Eagle, on the Mississippi River, Kentucky Union soldier John T. Harrington provided some interesting opinions on the Confederates that were his supposed enemies and his service in Mr. Lincoln's army.Saturday, May 14, 2011

One Woman's Take

Dear Sir

The negros have taken up the notion, or rather it has been taught them by beggers and Gipsies, that as soon as you were elected they would all be free. They have commence their work of poisining and Incendiaryism. Now all I want to know is make them know it, so that they may go to work and wait until the next presidential Election to cut up again. I wish you would ask your Estimable Lady how she would like, "just as she gets a good cook for some stragling begger, peddler or fortune teller to come along and pursuade her that some one would give her higher wages on the other side of town. For God sake Dear Sir give us women some assurance that you will protect us, for we are the greatest Slaves in the South.

Respectfully

Sue H Burbridge

It is not known if Abraham Lincoln responded to this woman's fears or even if he read her letter. Knowing Lincoln I would not be surprised if he did both. Letters like this might be one of several reasons he treated the border slave states with kid gloves early in the war.

Her mention of gypsies and peddlers as the cause of trouble with slaves was a common concern among citizens of the slave states. Whether these traveling salesmen and wandering performers were responsible or not, they often drew the wrath of community members concerned with personal safety and maintaining their slaves as property. Peddlers were particularly targeted for vigilante harassment. Treatments of tar and feathers or a ride out of town on a rail were not rare. For the citizens of the slave states the law of self preservation remained primary to any rights bestowed by government and written laws.

Friday, May 13, 2011

A Threat?

I found the above short note at the Library of Congress. It was sent to President Abraham Lincoln's friend, Kentuckian Joshua Speed, by Kentuckians Joshua F. Bullitt, Charles Ripley and W. E. Hughes and apparently was intended for both Speed and Lincoln, as it says "Care The Prest.," and appears in the Lincoln papers. It goes against my previous thinking that Kentuckians were not contemplating the possibility of emancipation in 1861. It reads:

I found the above short note at the Library of Congress. It was sent to President Abraham Lincoln's friend, Kentuckian Joshua Speed, by Kentuckians Joshua F. Bullitt, Charles Ripley and W. E. Hughes and apparently was intended for both Speed and Lincoln, as it says "Care The Prest.," and appears in the Lincoln papers. It goes against my previous thinking that Kentuckians were not contemplating the possibility of emancipation in 1861. It reads:Tuesday, May 10, 2011

CW 150 at History.com

The more I see the less I like the programming on History (formerly the History Channel). With shows like Ice Road Truckers and Swamp People, which have almost nothing to do with History per say, I have little reason to spend time on channel 46 of my basic expanded cable.

The more I see the less I like the programming on History (formerly the History Channel). With shows like Ice Road Truckers and Swamp People, which have almost nothing to do with History per say, I have little reason to spend time on channel 46 of my basic expanded cable.Wednesday, May 4, 2011

The Union War

It seems that Dr. Gary Gallagher's new book, The Union War is causing quite a stir among Civil War scholars. In the book Gallagher calls into question several historians' recent interpretations of the main motivation for the North fighting the war.

It seems that Dr. Gary Gallagher's new book, The Union War is causing quite a stir among Civil War scholars. In the book Gallagher calls into question several historians' recent interpretations of the main motivation for the North fighting the war.Tuesday, May 3, 2011

"Let Justice Be Done!"

To say the least 1864 was a difficult year for white Kentuckians. Their physical world was being torn apart by raiding guerrillas and their social world was being turned upside down as African Americans flocked to the Union army to enlist.

To say the least 1864 was a difficult year for white Kentuckians. Their physical world was being torn apart by raiding guerrillas and their social world was being turned upside down as African Americans flocked to the Union army to enlist.