Saturday, March 31, 2018

Recent Acquisitions to My Library

Since reading Forts Henry and Donelson: The Key to the Confederate Heartland by Benjamin Franklin Cooling a number years ago, I've been a fan of Cooling's research and writing. To the Battles of Frankin and Nashville and Beyond: Stabilization and Reconstruction in Tennessee and Kentucky, 1864-1865, is his follow-up work to Fort Donelson's Legacy: War and Society in Tennessee and Kentucky, 1862-1863. The tragic fighting at Franklin is one of those battles that continues to draw significant attention due to its controversial high number of Confederate casualties. I'm interested in reading Cooling's take on the engagement, as well as his interpretation on Reconstruction as it was experienced in these two important Civil War states.

With 2018 being Frederick Douglass' bicentennial birthday, it is not surprising that some new scholarship would appear. This work caught my attention because of its focus on the role of religion in Douglass' life. From what I've read about and from Douglass, I had never thought of him as being particularly religious. However, due to his life experiences, I could see where he might see the influence of divine Providence. In addition to this work, I believe that Yale's David Blight is also releasing a Douglass biography this year.

I saw The Aftermath of Battle: The Burial of the Civil War Dead by Meg Groeling in the Petersburg National Battlefield's book store recently, and then located a used copy on Amazon for a steal, so I bought it. I just finished reading it this past week and found it quite informative as it covers a number of diverse topics related to burying the dead from the Civil War' battlefields.

While I lived in Kentucky I became acquainted with the life of Richard Mentor Johnson. Johnson, Martin Van Buren's vice president, supposed slayer of Tecumseh, and the common-law husband of an enslaved woman of color, who sent his mixed race daughters to be educated intrigued me. I was just as much fascinated as to why no one had attempted a modern study about this seemingly fascinating man's life and times. Johnson is also known for founding an academy for American Indian young men on his Kentucky lands. I am especially interested in learning if the Johnson family benefited financially through their work as Indian agents to tribes in the South. I have high hopes.

Thursday, March 29, 2018

Petersburg's Railroads - U.S. Military Railroad

The final rail line we will cover is the United States Military Railroad (USMRR). This important line started at City Point (present-day Hopewell) and used the majority of that prewar rail line before branching off and turning south, and then eventually southwest. It began construction in June of 1864, and as the Union army extended its line of earthworks attempting to cut Confederate railroads and roadways, the USMRR extended along with it.

Established along the rail lines were depots where supplies brought by ship to City Point were then loaded on to the trains and transported out to the front line troops in their earthen fortifications. The depots often took on the names of Union officers such as Meade's Station, Birney's Station, Parke's Station, and Patrick's Station.

The importance of the deep-water supply base at City Point has received too little attention in regard to the Union success in the Petersburg Campaign. Here ships and barges from Boston, Philadelphia, New York, Baltimore, and Washington D.C., brought war materiel such as train engines and cars, heavy artillery, wagons, pontoons, uniforms, small arms, and draft animals for the army's use. Also the ships brought a steady and welcome supply of rations to the Union troops in the field.

Some soldiers mentioned receiving fruit, vegetables, various meats, and coffee, due to the efficiency of the USMRR. Some soldiers even praised the ability of the railroad to bring soft bread, still warm when they received it on the front lines, from the busy bakeries at City Point. In addition, a series of field hospitals along the rail line ministered to the sick and wounded of the Union army. The worst medical cases received transportation by rail from the front lines to the massive hospital complex at City Point, or water transport back to Washington D.C.

Constructed as quickly as possible, the USMRR often went ungraded. Lt. Col. Horace Porter of Gen. Grant's staff mentioned that, "It ran up hill and down dale, and its undulations were so marked that a train moving along it looked in the distance like a fly crawling over a corrugated washboard." When the campaign concluded in April 1865, the USMRR had laid 21 miles of track. One source explained that the line incorporated 25 locomotives pulling 275 cars, which logged approximately 2,300,000 miles during the 292 day campaign.

The last major Confederate offensive in the Petersburg Campaign, the attack on Fort Stedman on March 25, 1865, east of Petersburg, was intended in part to threaten the USMRR, which only sat about a mile behind Fort Stedman. Confederate Gen. John Brown Gordon believed that if he could pierce the Union earthwork line at Fort Stedman, as well as the Federally-reversed line of the old Dimmock line, the Yankees would be forced to contract their lines back in order to protect their railroad supply line and its terminus at City Point. If this happened it would provide Lee with the opportunity to detach troops, or leave himself, to help Gen. Joseph Johnston against Gen. Sherman in North Carolina. Although the attack was initially successful, a Union counterattack and artillery fire from neighboring forts quickly ended the brief Confederate success.

The USMRR was the key toward the backdoor of Petersburg, and Grant used it well.

Wednesday, March 28, 2018

Petersburg's Railroads - Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad

Petersburg's last antebellum rail line was the Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad, which traversed that route's 85 miles. It received its charter in 1851, started construction two years later, and began operating in 1858. Like the Southside Railroad, the Norfolk line med a number of natural obstacles that required conquering, primarily bridging the Elizabeth River and crossing part of the Great Dismal Swamp. Virginia Military Institute graduate, railroad engineer, line president, and future Confederate general, William Mahone, designed ingenious ways to circumvent these problems. He developed drawbridges to cross the river and a log railroad bed to help traverse the swamp.

As with Petersburg's other antebellum railroads, primarily enslaved individuals provided the majority of the labor required to do such large projects. The advertisement above that ran in the Petersburg Daily Express in 1855, called for leased slaves to work on the Norfolk and Petersburg and offered "liberal prices and good treatment."

The station depot for the Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad ran just a couple of city blocks behind the Bollingbrook Hotel (shown above) on Bollingbrook Street. Travelers on this line, as well as the nearby Southside Railroad, preferred the accommodations of the Bollingbrook due to its convenient location. Those who traveled the Petersburg Railroad most often stayed at Jarrett's Hotel on Washington Street, just across that thoroughfare from that line's depot. These hotels offered guests all types of services in addition to lodging. Travelers could have their laundry cleaned and pressed by hotel laundresses, and they could have their hair cut or beards shaved by hotel barbers. Lodgers could dine at the hotel's restaurants where enslaved and free people of color cooked and waited on their guests. With such services bringing in an additional steady revenue, it is easy to see the hotel's interest in not connecting the various rail lines.

Early in the war the Norfolk and Petersburg line was extremely important. Since Norfolk and its ship industry was an early target of the Union navy and army, the railroad was used to remove heavy coastal artillery to safer in-land locations. When federal forces captured Norfolk in the spring of 1862, the Norfolk and Petersburg line was forced to reduce its travel distance to about 35 miles to the depot at Ivor. Interestingly, this rail line ran directly through much of the June and July 1864 fighting of the Petersburg Campaign. In fact, the line ran just a stone's throw away from the entrance to the mine shaft dug under the Confederate fortifications that resulted in the Battle of the Crater. One has to wonder if when making his famous counterattack on the afternoon on July 30, 1864, Gen. Mahone pondered about the unusual turn of events occurring near his railroad line.

Tuesday, March 27, 2018

Petersburg's Railroads - Southside Railroad

Petersburg's commercial community had long desired a western route, one that could bring primarily tobacco, but other crops such as wheat, from that region of the state. Before a viable rail line Petersburg had primarily relied on the Appomattox River and its canal which circumvented the fall line to get the tobacco from more inland towns such as Farmville. Petersburg's desired were met when the Southside Railroad was chartered in 1846. The 123 mile route from Petersburg to Lynchburg reached completion in 1854.

This route also provided travelers with a way to get to western locales. From Petersburg, train-bound passengers could ride the cars to Lynchburg and from there continue west to Knoxville, Chattanooga, Memphis, or Atlanta on the Tennessee and Virginia and Tennessee and Georgia parts of the connector lines.

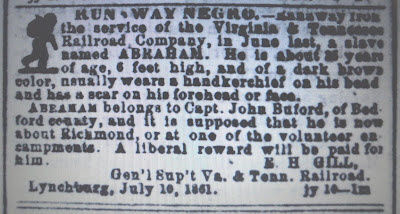

Of course, a majority of the labor required to build Petersburg's railroads came from enslaved workers. Major railroad contractors placed advertisements seeking to both purchase and lease surplus slaves from area owners and brokers to do the grueling work of grading railroad beds, sawing and placing timber ties, and laying iron track. The General Superintendent of the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad, which was a connector line to the Southside Railroad in Lynchburg, posted the above advertisement seeking to locate a runaway slave named Abraham, who was rented from his owner to work on the railroad. It is interesting that the superintendent suspected that Abraham may be attempting to gain some anonymity at one of the Confederate encampments around Richmond.

The Southside Railroad was Gen. Grant's final objective, as it was the last supply artery of Lee's army at Petersburg. Grant's Eighth Offensive (March 29-April 1), which included actions at Lewis Farm, White Oak Road, Dinwiddie Courthouse, and Five Forks, snapped the Boydton Plank Road and put Federal forces within striking distance of the Southside Railroad. The Federals finally severed the line on April 2, 1865, when the VI Corps broke through Lee's thinly defended line at what is now Pamplin Historical Park. Some of the troops who broke through made their way to the Southside Railroad and tore up track. In fighting later in the day at Sutherland Station, more track was captured and secured. The Southside Railroad Depot in Petesburg (shown above) came under Union control on the morning of April 3.

During the Appomattox Campaign the Southside Railroad was re-gauged by Union soldiers in the IX Corps to fit their Military Railroad rolling stock. Doing so allowed them to use old Confederate infrastructure such as the bridge over Rohoic Creek shown above without having to build new structures. These efforts helped supply elements of the Union army as it pursued Lee westward. The Southside Railroad ran through Appomattox Station, near Appomattox Courthouse, where Grant forced Lee's surrender on April 9.

Monday, March 26, 2018

Petersburg's Railroads - Richmond and Petersburg Railroad

The Richmond and Petersburg Railroad was also being built at the same time construction proceeded on the City Point Railroad. This line connected the two industrial cities. However, many of Petersburg's influential citizens did not favor the line as they thought it would potentially take commerce to the larger state capital city rather than keep it in Petersburg. Some of those concerns were alleviated when it was determined that the southern terminus of the line would be on the north side of the Appomattox River. Therefore, any cargo moving north at least had the inconvenience of having to be ported across the river from Petersburg to Chesterfield County to get to Richmond. The Richmond and Petersburg line also provided travelers with a route to the state capital and north beyond. Other rail lines connected northern Virginia locales to Washington D.C., Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York City, and Boston. It was not until 1861 that a railroad bridge across the Appomattox River was constructed in effort to increase railroad efficiency.

Like its fellow Petersburg lines, the Richmond and Petersburg Railroad published schedules in the city's newspapers. These instructed the various members of the community when different types of trains were departing and were expected to arrive. The mail train had a specific departure time, the freight trains had a specific departure time, and passenger trains had a specific departure time. In the same advertisements were information on fares. The fares, as one might imagine, varied depending on the distance traveled. As the above ad shows it cost $1.35 for an adult white traveler to ride between Petersburg and RIchmond. Children between five and twelve cost $.85; as did slaves who rode in the "Servant's Car." The ad also stipulated that "Servants will not be permitted in the first class cars, except when in attendance on infants or sick persons; in which cases the same fare as for white persons will be charged."

During the Civil War, the Richmond and Petersburg Railroad proved important to the Confederate army in its many attempts to shuttle troops between the front lines of the cities' defenses under attack by Grant's forces. The line was a particular target during the Bermuda Hundred Campaign in the spring of 1864. However, it received protection from a series of earthworks known as the Howlett Line that stretched across this strip of land between the James and Appomattox Rivers.

The Richmond and Petersburg line also suffered due to it being a single track, with few switch or pull off points for cars to pass going in different directions. Finally, its close proximity to the Union army's eastern front at Petersburg made the trains that ran on its tracks a target for that force's artillery fire. Despite the great effort to cut it, the Richmond and Petersburg Railroad remained active until Gen. Lee's men evacuated the two cities on the night of April 2, 1865.

Friday, March 23, 2018

Peterburg's Railroads - The City Point Railroad

The City Point Railroad, a short nine-mile line from Petersburg to the town and docks of City Point (present-day Hopewell), at the confluence of the Appomattox and James River was chartered in 1836 and completed in 1838. At the time, some Petersburg citizens viewed this line as unnecessary, as many ships could pick up commerce and crops as easily in Petersburg's eastern wharves as at City Point's. But to do so the Appomattox River near the Cockade City constantly needed dredged, an inconvenience, both in cost and effort.

In 1847, the town of Petersburg purchased the City Point Railroad and renamed it the Appomattox Railroad. In 1854, the Southside Railroad purchased the diminutive line from the city and made it the eastern section of that line. Due to its relatively short distance, this line carried far more commercial and freight business than passenger service.

During the Civil War, what was the old City Point Railroad was virtually useless as the Union army and navy took control of the lower James River early in the contest, thus Confederate friendly ships were not able to carry the goods delivered to the the City Point wharves by the railroad cars. However, it did serve for a time as a somewhat alternate route to the capital city of Richmond up the James River, until the Federal Army of the James under Gen. Benjamin Butler took control of the Bermuda Hundred peninsula. Once in Union army secured City Point in the spring of 1864, it used part of its short route for the United States Military Railroad.

It was on this part of the line that ran behind the former Confederate earthworks of the Dimmock Line, east of Petersburg, which were captured in the fighting that occurred on June 15-18. It was here that the Union forces brought up by rail the famous though short-lived 13-inch mortar known as the "Dictator."

Thursday, March 22, 2018

Petersburg's Railroads - The Petersburg (Weldon) Railroad

Last Monday evening I was honored to speak to a local group of history enthusiast about Petersburg's railroads. I covered the antebellum as well as their Civil War history. It was after all the railroads which placed Petersburgs in the crosshairs of Gen. Grant's sights.

I've not shared much on Petersburg's railroads on this forum, so I thought I'd take some of the material that I covered in the history talk by making a handful of posts. The first one will cover the Petersburg Railroad.

The Cockade City's oldest railroad was the Petersburg Railroad, also sometimes known as the Petersburg and Weldon Railroad. It ran from its depot on Washington Street (shown on the right side of the image above) to Garysburg, North Carolina, on the north side of the Roanoke River and then to the adjacent town of Weldon, on the south side of the Roanoke River. From Weldon, other connector lines ran to the coastal city of Wilmington, North Carolina.

The Petersurg Railroad received its charter from the Virginia legislature in 1830, and opened in 1833, making it one of the early railroads in the United States. Although the line served both commercial as well as passenger use, it figured more prominently int the former than the later. However, a travler remarked that "a journey which formerly required two days, is now performed between breakfast and dinner, and may be retraced by tea time." The sixty mile trip now only took four hours!

The Petersburg Railroad evolved partly out of a rivalry with Norfolk for the tobacco business of northern North Carolina. After its opening in 1833, its effect on Petersburg was almost immediate. The railroad brought in new businesses and spurred the creation of more rail lines that will be discussed in future posts.

During the Civil War, and due to the Petersburg Railroad's Deep-South connections, it became a primary focus for the Union army. Grant and Meade made two separate efforts to attain the line. The first, what has become known as Grant's Second Offensive (June 22-23) ended in a failed attempt to cut the line when troops of the II and VI Corps moved west from their lodgement on the Jerusalem Plank Road. The II Corps ran into a furious counterattack by Gen. William Mahone's Division, which resulted in over 2000 captured Union soldiers and which left the VI Corps unsupported and vulnerable, causing both corps to retreat after briefly reaching the rail line near where Richard Bland College is today.

The other significant military actions along the line occurred during Grant's Fourth Offensive (August 1864). The first of that fighting occurred where the June actions happened and became known by a couple of names: The Battle of Weldon Railroad, or the Battle of Globe Tavern. Fighting broke out on August 18 as Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren V Corps secured a section of the track and held on tenaciously as the Confederates counterattacked for three days trying to recapture the vital rail line. With reinforcements from the IX Corps, the federals held on and extended their earthworks west of the railroad.

A few days later on August 25, Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock's II Corps, just returned to the Petersburg front after a tour of duty fighting north of the James River at Deep Bottom, was attacked by Confederates just about five miles south of Globe Tavern on the rail line at Ream's Station. In the savage combat that resulted, Hancock was forced to relinquish the field and the railroad to the Southerners. However, since the federals had control of the rail line south of Petersburg at Globe Tavern, the Union defeat did not significantly alter the situation.

By capturing the Petersburg Railroad south of the city, the federals forced the Confederates to seek an alternate route to get their supplies to their troops at Petersburg and Richmond. What the Southerners devised worked, but proved to be and inefficient alternative. They unloaded their entrained north-bound supplies at Stoney Creek Station, about 18 miles south of Petersburg, onto horse and mule-drawn wagons that then went cross-country to the west to Dinwiddie Courthouse and then finally up the Boydton Plank Road into Petersburg.

With the Petersburg Railroad under control in August 1864, Grant set his sights on capturing the Boydton Plank Road and the Southside Railroad farther to the west. Those two goals would prove to be a hard road to travel, as they would not be attained until late March and early April 1865.

Friday, March 16, 2018

Tonsorial Artists!

In my seemingly never-ending search for information on antebellum black barbers in the mid-South, I felt that I had exhausted my search on platforms that allow for key-word searches. However, recently a friend sent me an article from the early twentieth-century newspaper that used the term "tonsorial artist" in reference to a barber. I had come across that particular phrase in other advertisements and articles a few times, but until today, for some reason, I never thought to use it as search term.

As I've mentioned in other posts on this subject, during the antebellum period, it was common for barbers to spend as much or more time shaving customers than cutting their patrons' hair. Although they might have charged less for shaving services than hair cuts, shaves came much more frequently. I thought there might be a connection to tonsorial and tonsils, being that that area prominently receives shaving. There might be something there, but it appears that tonsorial is taken more as an archaic synonym for barbering or shaving.

Well, it didn't take me long to try. I searched 1850s Virginia newspapers this afternoon in the Chronicling America newspaper feature on the Library of Congress website. I turned up three references in the Richmond Daily Dispatch.

The first one that I found was in the February 7, 1857 edition and came in the form of a traditional advertisement. The McNaughton brothers in Richmond sought to remind citizens of that city that they maintained their shop on 12th Street below Duval's Drug Store. There they offered the normal barbering services, including dying hair.

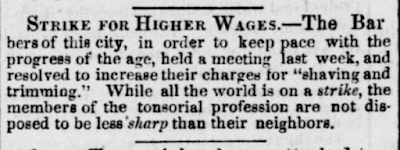

The next notice I located appeared in the March 7, 1854, issue. The editor stated that Richmond's barbers, almost all of whom were African American, showed solidarity by meeting and resolving to increase their prices for shaves and haircuts. The brief article ends with a pun and insinuated that black barbers took notice of other workers whose labor was in demand and that fact proved that "members of the tonsorial profession" were as "sharp" or perceptive as others who demanded higher wages for their work.

I wonder if a newspaper posting such as this last one, which did not take on the traditional appearance of a classified advertisement as shown at top, was paid for by Cook, or if it was run as a type of public service announcement. Regardless, all of these newspaper appearances show that black barbers were visible businessmen who contributed valuable services to their local communities.

Monday, March 5, 2018

1860 Black Barbers in Farmville, Virginia

In my continuing search for Virginia's antebellum black barbers, I recently searched the Farmville, (Prince Edward County) Virginia, 1860 census. The town's population was just about 925 people that year. According to my previous research I figured that a town of Farmville's size probably had the size to support a barber or two or three, and such was the case.

The first black barber that I came across was Thomas Harvey. This twenty-three year old mulatto man apparently lived in a hotel in town as all of the individuals (about thirty-five) in this household are under Norvell Cobb's name, who is listed as a hotel keeper. In addition many of the people living there have various occupations such as lawyer, druggist, merchant, student, jeweler, etc., that one would expect to find in town environment.

Barber Thomas Harvey is the only man of color listed as living in the hotel. Perhaps he cut hair and shaved beards in the hotel working for the building's owner and manager. Interestingly, there were two "negro traders," also residing at the hotel at this time.

J.W. Brightwell, a thirty-eight year old slave trader (above) had real estate valued at $10,000 (about $280,000 in present dollars) and personal property valued at $7880 (about $230,000 present dollars).

John Jenkins apparently was not as successful as Brightwell, as he is not shown as having any wealth.

Farmville's other two barbers apparently worked at the Randolph House hotel. Andrew Lilley, a twenty-two year old black man who had $400 in personal property, and Crawley Mitchel , a forty year old mulatto man, who had no personal wealth are both shown residing in the same household and likely worked together.

I did not find any black barbers in the 1850 Prince Edward County census. I am curious if the 1860 barbers continued to stay in Farmville after the Civil War. I'll try to remember to let you know what I find out.

1867 Farmville map courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Saturday, March 3, 2018

George Washington Ruffin, Richmond Free Black Barber

At present the museum has some fantastic photographic images of Richmond's African American community from the antebellum years to the Civil Rights era. One fascinating image showed George Washington Ruffin, one of Richmond's many free black barbers. The photograph is owned by the Amistad Research Center at Tulane University, who also owns a collection of the family's correspondence. George Washington and Nancy Ruffin's impressive images can be viewed on the Amistad Research Center's website here.

Curious to learn more about Ruffin, I searched the 1850 census (shown above). It listed him as a fifty year old (born 1800) mulatto barber with $2000 in real estate. Also listed were Nancy, and their sons and daughters, all also listed as mulatto.

The Amistad Research Center's website explained that the Ruffins valued education as the way toward socioeconomic advancement and therefore Nancy and the children moved to Boston where a better education could be attained than in Virginia. Meanwhile, George Washington Ruffin remained in Virginia as financial provider for the family, presumably due to his established barbering business.

This appears to be corroborated by the 1860 census, which shows Ruffin as 60 years old and with $2000 in real estate and $1900 in personal property. With Ruffin is Joseph M. Thurston, a nineteen year old barber, who was likely Ruffin's apprentice. This official record seems to confirm that Ruffin had indeed developed a thriving barbering business which allowed him to save an impressive amount of wealth for a free man of color in 1860.

One of the Ruffin children took the opportunity for a Boston education and ran with it. George Lewis Ruffin, who is listed as fifteen (born 1834) in the 1850 census with his parents in Richmond, like his father, worked as a barber, but in Boston. George Lewis Ruffin read and studied law while cutting hair and shaving beards and ended up being the first African American graduate from the Harvard Law School in 1869. He was also the first black municipal judge in Massachusetts in 1883.

Hopefully, I can get my hands on the George Washington Ruffin papers someday to see if there are any insights into his life as a Richmond barber. Fascinating, just fascinating!

Friday, March 2, 2018

Personality Spotlight - Bradley T. Johnson

At work we have a significant archive of unprocessed antebellum letters relating to Gen. Bradley T. Johnson. I've not delved too deeply into them as yet. One quick glace showed that they are not the most legible, and some are written in one direction and then perpendicular back across the first lines. These should be fun to transcribe - (sarcasm!)

I had certainly come across Johnson's name in my Civil War reading a number of times, yet I realized that I did not know much anything about him. As so often happens, this got my historian's curiosity stirred, so I thought I do a little research to see what I could learn. I was not able to find a full biography published about Johnson. One reason for that may be that his papers are scattered in various repositories, and there may be others out there unprocessed such as ours with the primary source material necessary to form a good life story.

Johnson was born in 1829 in Frederick, Maryland. He had the benefit of an excellent education at Princeton and entered public life after graduation serving in a number of political positions in his native state before the Civil War. A strong Democrat, Johnson stumped for John C. Breckinridge in the 1860 presidential election. When the war came he was found helping organize Marylanders sympathetic to the Confederate cause.

In the summer of 1861, Johnson was on the staff of the 1st Maryland (CSA) serving as the regiment's major. The unit fought gallantly at First Manassas where promotions above elevated Johnson as well. As the 1st Maryland's Lieutenant Colonel, the regiment experienced a lull in active campaigning. However, Johnson benefited again from others' promotions and was made colonel of the 1st in the summer of 1862.

Bradley and the 1st Maryland served in Stonewall Jackson's Shenandoah Valley Campaign that spring and summer, fighting memorably against fellow Marylanders at the Battle of Front Royal. They followed up their Valley fighting by transferring to Richmond and opposing McClellan's forces in the Seven Days' battles.

When the 1st Maryland was disbanded in August 1862, Johnson was left without a command. He had caught the eye of Jackson though, who placed him in temporary command of a brigade whose commander was ill. In this position Johnson led troops successfully at Second Manassas. When the brigade commander returned Johnson was out again. However, Jackson soon tabbed Johnson for promotion to brigadier general, but he was denied.

Johnson remained in limbo for about six months in Richmond assigned to various duties about the city. He assisted the Army of Northern Virginia in the Gettysburg Campaign during the summer of 1863, and following that, he organized diverse Maryland units to form a force called the Maryland Line, In the spring of 1864 he helped defend Richmond against a Union cavalry raid seeking to burn the city and capture president Jefferson Davis, in so doing earning praise from his superiors for his leadership performance.

Working along with cavalrymen J.E.B. Stuart and Wade Hampton, Johnson finally earned his brigadier commission during the Overland Campaign. His cavalry assisted Jubal Early's move through the Shenandoah Valley the summer and fall of 1864. During the campaign Johsnon was tasked with attempting the liberation of Confederate soldiers held at Point Lookout prison. Unable to do so he returned to Early's command and assisted in the burning of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania with John McCausland's troopers. A consolidation of cavalry caused Johnson to lose his command and he was assigned to oversee the Confederate prison camp at Salisbury, North Carolina, where he served until the end of the war.

Johnson lived in both Virginia and Maryland after the war practicing law. He died near Amelia, Virginia, in 1903, and was buried in Baltimore.

I had certainly come across Johnson's name in my Civil War reading a number of times, yet I realized that I did not know much anything about him. As so often happens, this got my historian's curiosity stirred, so I thought I do a little research to see what I could learn. I was not able to find a full biography published about Johnson. One reason for that may be that his papers are scattered in various repositories, and there may be others out there unprocessed such as ours with the primary source material necessary to form a good life story.

Johnson was born in 1829 in Frederick, Maryland. He had the benefit of an excellent education at Princeton and entered public life after graduation serving in a number of political positions in his native state before the Civil War. A strong Democrat, Johnson stumped for John C. Breckinridge in the 1860 presidential election. When the war came he was found helping organize Marylanders sympathetic to the Confederate cause.

In the summer of 1861, Johnson was on the staff of the 1st Maryland (CSA) serving as the regiment's major. The unit fought gallantly at First Manassas where promotions above elevated Johnson as well. As the 1st Maryland's Lieutenant Colonel, the regiment experienced a lull in active campaigning. However, Johnson benefited again from others' promotions and was made colonel of the 1st in the summer of 1862.

Bradley and the 1st Maryland served in Stonewall Jackson's Shenandoah Valley Campaign that spring and summer, fighting memorably against fellow Marylanders at the Battle of Front Royal. They followed up their Valley fighting by transferring to Richmond and opposing McClellan's forces in the Seven Days' battles.

When the 1st Maryland was disbanded in August 1862, Johnson was left without a command. He had caught the eye of Jackson though, who placed him in temporary command of a brigade whose commander was ill. In this position Johnson led troops successfully at Second Manassas. When the brigade commander returned Johnson was out again. However, Jackson soon tabbed Johnson for promotion to brigadier general, but he was denied.

Johnson remained in limbo for about six months in Richmond assigned to various duties about the city. He assisted the Army of Northern Virginia in the Gettysburg Campaign during the summer of 1863, and following that, he organized diverse Maryland units to form a force called the Maryland Line, In the spring of 1864 he helped defend Richmond against a Union cavalry raid seeking to burn the city and capture president Jefferson Davis, in so doing earning praise from his superiors for his leadership performance.

Working along with cavalrymen J.E.B. Stuart and Wade Hampton, Johnson finally earned his brigadier commission during the Overland Campaign. His cavalry assisted Jubal Early's move through the Shenandoah Valley the summer and fall of 1864. During the campaign Johsnon was tasked with attempting the liberation of Confederate soldiers held at Point Lookout prison. Unable to do so he returned to Early's command and assisted in the burning of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania with John McCausland's troopers. A consolidation of cavalry caused Johnson to lose his command and he was assigned to oversee the Confederate prison camp at Salisbury, North Carolina, where he served until the end of the war.

Johnson lived in both Virginia and Maryland after the war practicing law. He died near Amelia, Virginia, in 1903, and was buried in Baltimore.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)