Sunday, March 29, 2020

Recent Acquisitions to My Library

If I am able to find some silver lining to this COVID-19 pandemic black cloud, it is that it is affording numerous opportunities to get in additional reading. Spending more time indoors, with no sports distractions, and not being a big television or movie viewer anyway, I am trying to use my God-given time to continue to learn . . . and share a few of my "Random Thoughts."

Most of my recent readings have come courtesy of my two full "to be read" shelves. I've pulled books off of it that have been there for years. I figure there is no real need to add new books when I have so many waiting to be read, therefore the lack of "Recent Acquisitions to My Library" posts.

However, several different circumstances added three new books to my library over the last month or so. My latest purchase is Civil War Places: Seeing the Conflict through the Eyes of Its Leading Historians, edited by Gary Gallagher and J. Matthew Galman. I almost bought this book last June at the Gettysburg College Civil War Institute where I heard a panel discussion by several of the book's guest authors. I've always enjoyed reading historians connections to subjects and places. Our book club at work chose this selection for our next read before the extent of the corona virus was fully known. And, we may not get to discuss it when we had planned, but I'll have it read and ready in case. Fingers crossed!

I know writing book reviews is something that a lot of people dread, but I rather enjoy it, especially if it is for publication. Every so often I have the opportunity to write book reviews for Civil War News and other publications. Last week I claimed Men is Cheap: Exposing the Frauds of Free Labor in Civil War America by Brian P. Luskey for an upcoming issue. Historian Amy Murrell Taylor calls Men is Cheap "A masterful work of historical research. Centering his story on a wide-ranging cast of brokers, speculators, merchants, soldiers, and formerly enslaved people, Brian Luskey examines deep flaws in the system of free labor at the very moment when it was supposed to deliver the nation from the oppression of chattel bondage. Luskey leaves no doubt that the Civil War marked a critical shift in the history of American labor and capitalism. Men is Cheap is an eye-opening and absorbing read." Sounds like a good one!

The good thing about maintaining an online "wishlist" of books is that from time to time one can monitor prices, and when a good deal comes along, snatch it up. Well, a few weeks ago I found an excellent buy on a hard copy edition of Through the Heart of Dixie: Sherman's March and American Memory by Anne Sarah Rubin. Memory studies are one of my favorite history genres, and I can't think of a much better memory study subject than Sherman's march to the sea.

Happy reading! Happy learning! Happy living!

Thursday, March 26, 2020

Deserters or Prisoners, or Both?

A prisoner of war category, which occurred quite often during the Petersburg Campaign, are those soldiers who willingly went over to the enemy. I think these men fall into somewhat of a nebulous zone. Are they deserters or prisoners, or both? I personally tend to associate the "deserter" label with those that left their armies, not going to the enemy, but away from the fighting, usually toward home. In effect, they are officially prisoners of war, and often were sent to camps for incarceration, but not being captured in battle or without resistance seemingly makes them different.

During the Petersburg Campaign, where the distance between opposing picket lines were sometimes measured by feet or a few yards, the opportunities abounded for worn out or frustrated soldiers to end their service by going over to the other side. Dusk, night time, and early mornings cloaked movements and enhanced chances of success. The Union army even posted messages that they would pay Confederates to bring in their rifles and equipment to encourage them to make the effort.

While recently reading Col. Elisha Hunt Rhodes' (pictured above) diary, published as All for the Union, I came across an entry in late February 1865 where he encountered a group of Southerners running the picket gauntlet. After serving as Officer of the Day on the picket line just southwest of Petersburg, Hunt returned to his winter quarters hut to catch a little sleep. Before nodding off, he "told the sergeant in charge of the guard at the hut not to allow any deserters to enter until he had called me. After sleeping a short time I heard some one say 'Colonel,' and looking up saw four Rebels standing in the hut."

Being so near the picket line, Hunt was understandably startled. He wrote, "My first thought was that I was captured, and reaching down into my boot leg (My boots were on.) I pulled out my revolver and drew the hammer back. The sergeant said 'Hold on, Colonel,' and recognizing his voice I woke up fully and realized the situation. The four Rebels were deserters and belonged to the 37th North Carolina Regiment. I examined them and took down their answers to certain questions on paper and then after taking the cartridges from their boxes, sent them with the memoranda to the Provost Marshal at [VI] Corps. The object of sending questions and answers in writing to Corps Headquarters is to see they tell the same story twice alike."

While taking down the information, one of the Tarheels told Rhodes that one of his comrades also wanted to come over and a gave Rhodes the friend's name. Sure enough, some firing was heard and another North Carolinian came bounding into the Union picket line. Rhodes took a chance and addressed the soldier by the name provided by his friend earlier. The new prisoner was astonished that Rhodes knew his name and regiment. As he was being taken away the deserter/prisoner said to Rhodes, "I know you Yankees are smart, but I cannot see how you found out so much about me." Rhodes replied "Oh, that is all right, we have ways of getting the news that you people know nothing about."

Wednesday, March 25, 2020

Refusing Capture: Capt. Theodore Gregg, Co. F, 45th Pennsylvania

It is perhaps not surprising that many of the accounts that I am finding involving soldiers captured during the Petersburg Campaign have an association with the Battle of the Crater. That particular fight is probably the most well known of the engagements during the 292-day campaign. The battle's unconventional approach and its dramatic nature of Union attack and Confederate counterattack in a relatively confined space helped ensure that an abundance of prisoners would result and that its participants would record their experiences.

Included in the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Series 1, Vol. 40, Part 1, page 553) is the report provided by Capt. Theodore Gregg of Company F, 45th Pennsylvania Infantry, made 10 days after the Battle of the Crater. The 45th Pennsylvania was in the 1st Brigade, 2nd Division, IX Corps and were among the regiments who made it into the virtual earthen deathtrap.

During the fight, Capt. Gregg reported:

"We heard the cheering of the men as they dashed forward; in a few minutes the works were filled with negroes. A major of one of the negro regiments placed his colors on the crest of the crater, and the negro troops opened a heavy fire on the rebels, who were at that time charging on the ruined fort. In a few moments the rebel force, headed by several desperate officers, dashed into the pits among us, where a desperate hand-to-hand conflict ensued, both parties using their bayonets and clubbing their muskets."

As mayhem and madness swirled around Capt. Gregg and his men the opportunities were ripe to become a prisoner of war. In fact, Gregg was too close for much comfort. He relayed that, "A large rebel officer, who appeared to be in command of the force, rushed upon me, and catching me by the throat, ordered me to surrender, at the same time bringing his revolver to my head. I succeeded in taking his revolver from him, and after a sharp struggle left him dead on the spot. A rebel soldier who had come to the rescue of his officer attempted to run me through with his bayonet, but was killed by Sergeant [David] Bacon of Company G. His sword was taken from him, but after a sharp contest he succeeded in recovering it and killing his antagonists."

Gregg's account, while vivid, pales into comparison in some details to that provided by Gregg's comrade, Lt. Samuel Haynes. Included in History of the Forty-fifth Regiment Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteer Infantry are some of the letters Haynes wrote during the war. Haynes' letter five days after the fight kicked up the intensity of the situation a bit. "Captain Gregg came down with me day before yesterday and took supper with me. He did some big fighting in the Rebel pits on Saturday. He killed a Rebel officer who led the charge. The Rebel caught Gregg by the throat and placing his pistol at his head demanded him to surrender. Gregg said: 'You impudent scoundrel, how dare you to ask me to surrender?' and wrenched the pistol from out of his hand, knocked him down with it, drew his sword and ran him through the body and left the sword in him. Then Gregg said 'You _________, I guess you are my prisoner now.'"

Capt. Gregg also mentioned that Capt. Rees G. Richards of Company G gallantly rallied his men, but "was fired at by a rebel and was seen to fall." Richards, however, was not killed or wounded. He literally dodged a bullet, but became a prisoner. Eventually incarcerated in South Carolina, he escaped in February 1865 and made his way to Union lines in Chattanooga the following month.

While Capt. Gregg escaped capture at the Battle of the Crater, his good luck ran out during the Battle of Peebles Farm on September 30, 1864. Captured in that fight he was exchanged and returned to the 45th in February 1865. After the war Gregg returned to Center County, Pennsylvania, married and started a family. He died in 1878 at age 58.

Sunday, March 22, 2020

Lewis R. Morgan, 4th Ohio Infantry - Medal of Honor

While I was at Poplar Grove Cemetery recently, I found the above marker for Sgt. Lewis R. Morgan, Company I, 4th Ohio Infantry. Morgan was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor on December 1, 1864, "for capture of flag from enemy's works" at Spotsylvania on May 12, 1864.

The 4th Ohio Infantry served in the Army of the Potomac's II Corps. During their effort to cut the Boydton Plank Road at the Battle of Burgess Mill, on October 27, 1864, Morgan was killed. He was only 28 years old.

Tuesday, March 17, 2020

Identification Badge of 5th USCI Soldier

The Battle of New Market Heights

occurred early on the morning of September 29, 1864, just southeast of

Richmond. This fight included two dramatic attacks by brigades in Brig. Gen. Charles

Paine’s division of United States Colored Troops against the earthen

fortifications of the famous Texas Brigade. Extreme examples of courage

resulted in fourteen African American soldiers earning the Medal of Honor for

their heroism at New Market Heights.

The first brigade to attempt an assault

of the works was commanded by Col. Samuel Duncan and consisted of the 4th

and 6th United States Colored Infantry. These units attacked in

battle line formations with the 6th following in echelon to the left

and just behind the 4th.

Encountering obstructions placed in

front of the earthworks by the Confederates, the two black regiments took

severe casualties as they attempted to reach the works. Three African American

soldiers from the 4th and two from the 6th received their

medals for rescuing their regimental or U.S. flags or rallying their comrades

when their white officers were either killed or wounded.

The small brigade eventually fell back

due to the severe number of casualties they received; over 55% of the men were

killed, wounded, or captured. Sgt. Maj. Christian Fleetwood, a man of few

words, but one of the Medal of Honor recipients for his heroism this day, noted

in his diary for September 29, “Charged with the 6th at daylight and

got used up, Saved colors.”

Next to attack was Col. Alonzo Draper’s

Brigade, which included the 5th, 36th and 38th regiments.

This brigade attacked in column, and although they took severe casualties, too,

they were able to break through the Confederate earthwork line. Nine black men

from these units received the Medal of Honor.

Although he did not receive the Medal of

Honor, Peter Turner of the 5th United States Colored Infantry was

“wounded severely” in the New Market Heights fight. Turner was apparently a

free man of color before the war, from Elizabeth City, North Carolina, and enlisted

in Company I, there on December 10, 1863. Turner carried this identification

tag with him during the war until he mustered out of service on September 20,

1865. Today, the tag is among the many significant artifacts in the care of

Pamplin Historical Park and the National Museum of the Civil War Soldier.

Saturday, March 14, 2020

Dying Close to Home: Cpl. Anderson Carrington, Co. C, 117th USCI

I apologize for the lack of recent posts, but I'm sure that I'm not the only one who feels that the last week and a half has been a true time of trial. However, in an effort to regain some sense of normalcy, I thought I'd share another soldier's story from Poplar Grove National Cemetery. These posts are usually titled "Dying Far From Home," but this particular story has somewhat of a different twist.

Having lived in Kentucky for six years, and thus studied some of the United States Colored Troops regiments raised there, I was fairly familiar with the 117th USCI (Infantry). The 117th was raised at Covington, just across the Ohio River from Cincinnati. Like other black Kentucky troops, their recruitment was delayed until 1864. Once organized, equipped, and trained they were transferred to Baltimore, and then to the Petersburg front, where Gen. Grant was grappling with Gen. Lee.

The spring of 1865 found the 117th (officially part of XXV Corps) serving on detached duty with the XXIV Corps near Hatcher's Run, southwest of Petersburg. They joined as part of that corps in the capture of Petersburg on April 3, and then pursued the Army of Northern Virginia to the surrender at Appomattox on April 9, playing an important role as part of the force that cut off any possible chance of further retreat to the west. After the surrender, the 117th returned to Petersburg and City Point as occupation troops for a few months before being sent to the Texas and Mexico border, where they remained for over two years before being mustered out of service.

It was while on post-surrender occupation duty in Petersburg that Anderson Carrington enlisted in the 117th. Carrington's complied service records show his enlistment date as April 28, 1865. Unlike the majority of his comrades who hailed from the Bluegrass State, Carrington appears to have been enslaved in Petersburg before and during the Civil War. The 20-year-old recruit is listed as being 5 feet 4 inches tall, with a "brown" complexion, and having previously worked as a "tobacconist." Laboring in Petersburg's many tobacco factories was a common occupation for both enslaved and free people of color during the antebellum years. Carrington eventually received a $300 bounty for his service commitment.

Although Pvt. Carrington enlisted after the Appomattox surrender, it appears that he took his soldier responsibilities seriously, as he appears as "present" on each muster card up to his final muster out. As additional evidence of this commitment, he received a promotion to corporal on November 1, 1866, in Brownsville, Texas.

But, obviously, Carrington's life story doesn't end there. We do not know Cpl. Carrington's line of thinking nor direction of immediate travel when he left the service in the fall of 1867. However, it appears that he returned to Virginia by 1869, as I found a marriage record for Carrington to Neila Ann Bruce on December 29, 1869 in Halifax County, Virginia. Another marriage record shows for Carrington four years later. This one wed Martha Smith on November 26, 1874, in Petersburg. Yet another marriage record appears for Carrington tying the knot with Bolena (Paulina?) Pryor in Petersburg on May 28, 1879. I was unable to find Carrington in the 1870 census.

Anderson Carrington does appear in the 1880 census in Petersburg. He is listed working in a tobacco factory and living with Paulina, his wife, who worked as a laundress. Also in the household was two-month-old daughter Martha, and brother-in-law Samuel Pryor, who worked as a carpenter. Several other Pryors were neighbors. Carrington also appears in an 1890 veterans census, living in Petersburg. I wonder if he participated in any G.A.R. activities?

In 1910, Petersburg remained Carrington's hometown. That census shows he was still married to Paulina and they had a 16-year-old son named Peter. Carrington's age is noted as 62 and he is shown as a "laborer" working "odd jobs." He could apparently read, but not write, and owned his own home mortgage free.

Records show that Anderson Carrington died before the next census. His death certificate indicates he died on October 9, 1916, from cerebral apolexy, a stroke. Although Carrington's military enlistment record shows his place of birth as Petersburg, his death certificate (according to information provided by Paulina) states that he was born in Charlottesville. It also lists his father as Richard Carrington and his mother was Millie.

The last bit of information on Carrington's death certificate is that he was buried in Poplar Grove National Cemetery two days after he died. He rests in peace there today in burial plot #5592.

Tuesday, March 3, 2020

11 Years . . . and Counting

Today, March 3, 2020, marks the eleventh anniversary of the birth of "Random Thoughts on History." Eleven years has resulted in 1349 posts. That is about 122 posts per year on average, or about ten posts per month.

Some years have resulted in prolific production. During the blog's first year, I churned out 178 posts. In 2012, I must have been in a zone, breaking the 200 posts barrier for the first and only time. I came close again the following year when I fell only seven posts short. Other years seemed like a drought, like 2011 (74), 2016 (75), and 2017 (78). With so many posts, more than once, I've had to use the blog's search feature to check and see if I had already posted on a specific subject, as I've made an effort to not duplicate.

Over the years, I've developed a number of themed series posts. Some of the most common are:

"Recent Acquisitions to My Library," posts make up over 35 additions.

"Just Finished Reading" book reviews are over 230 of the 1349 posts.

"Zooming In" photo manipulations are about 20 posts.

Hundreds of other singular posts relating to the blog's subtitle of "American, African American, Southern, Civil War, Reconstruction, Public History books and topics" fill "Random Thoughts on History's" pages.

It is my hope to continue posting as long as I enjoy doing so. Sharing my "Random Thoughts" has brought me friends, knowledge, and an ever growing appreciation for sharing the benefits of learning history.

Thank you for reading!

Monday, March 2, 2020

Freedom through Fighting - William Griffin, 7th USCI

Service in the United States army during

the American Civil War was one way enslaved men broke their chains of bondage.

Finally allowed to officially enlist in the Federal army when President Abraham

Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation took effect, thousands of enslaved African

American men made their way to recruiting stations in areas occupied by the

Union army.

In slaveholding yet loyal Border States,

like Kentucky, Maryland, Delaware, and Missouri, owners could sometimes file

claims and receive compensation for the emancipation of their enslaved property

who enlisted in the Union army. Such a deed of manumission exists in the

collections of Pamplin Historical Park and the National Museum of the Civil War

Soldier.

On September 28, 1864, William Griffin

of Worcester County, Maryland, filed a “deed of manumission and release of

service” in Baltimore for his former slave, Charles E. Griffin, who enlisted on

November 1, 1863, in Company K of the 7th United States Colored

Infantry (USCI).

Charles E. Griffin’s service records

indicate that he was 23 years old when he enlisted in Berlin, Maryland.

Described as 5’ 5 3/4” tall, with a mulatto complexion, Griffin officially

mustered into service at Camp Stanton in Charles City, Maryland, on November

12, 1863, enlisting for three years. Upon his muster into service Griffin received

a promotion to sergeant.

The 7th USCI was initially

detailed to Florida, in the Department of the South, as part of the X Corps.

Afterwards transferred to South Carolina, and finally Virginia, the 7th served

on the Bermuda Hundred, then in the earthworks just outside of Richmond, as

Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s Union forces tried to capture Petersburg and Richmond.

The 7th USCI battled bravely during the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm on

September 29, 1864, showing tremendous fortitude in attacks on well defended Fort

Gilmer. Amazingly, Charles E. Griffin survived the desperate fighting at Fort

Gilmer. During October 1864, the 7th helped man earthen Fort Burnham

(formerly Fort Harrison), which the Federals had captured from the Confederates

on September 29.

It was during an exchange of artillery

on October 10, 1864, that Sgt. Griffin received a mortal wound in the abdomen

by a piece of exploding shell. Taken to a nearby field hospital, he died the

following day. Described in his service records as “a brave man, cool in

action, and a good soldier,” Griffin rests today in Section D, Grave 237 at the

Fort Harrison National Cemetery.

Although sadly Charles E. Griffin did

not live to see it, his surviving African American comrades of the XXV Corps

were among the first troops to enter Richmond on April 3, 1865, effectively

putting yet another nail in the coffin of slavery.

Sunday, March 1, 2020

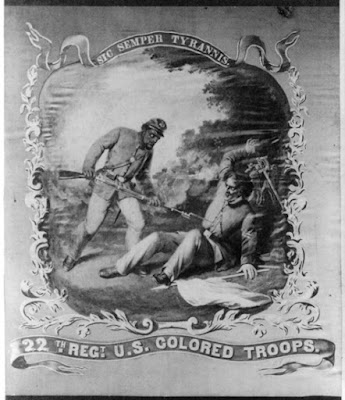

Dying Far From Home: Pvt. Charles Alexander, Co. K, 22nd USCI

Whenever I can, or just when I need take a moment away from the busyness of life, I take a short drive over to Poplar Grove National Cemetery and stroll through the thousands of graves there. Doing so restores a sense of humility and gratefulness that few other places can. Included among those buried in Poplar Grove are a number of men who served in various United States Colored Troops regiments. Since moving back to the Petersburg area in 2015, I've made an effort to show my appreciation to them by doing some research on their time in service and posting the information here for others to read and also offer their gratitude.

Resting in grave number 4417, just a few steps inside the cemetery's entrance gate, is Pvt. Charles Alexander, who fought with Company K of the 22nd United States Colored Infantry (USCI). The 22nd was one of the many regiments that was raised primarily of men from Pennsylvania and who mustered and trained at Camp William Penn, which was just outside of Philadelphia.

Pvt. Alexander's compiled service records tell us that he enlisted in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, on December 30, 1863. Since his service records state that he was born in Centre County, Pennsylvania, I wondered if I could locate him in the 1860 census. Doing so, would tell me more about him. I was fortunate! I found him!

Alexander was on Eden Township's enumeration in Lancaster County. He is shown as a 30-year-old head of household with the occupation of "farm hand." Living with him was his 27-year-old wife Emaline Alexander, 6-year-old daughter Savila A. Alexander, 4-year-old son William E. Alexander, and 1-year-old son Judge Burnsides Alexander. One has to wonder why Charles named his youngest Judge Burnsides. Did a Judge Burnsides do Charles a favor somewhere along his life path for which he was thankful? Hmmmmmm. Also living with the Alexanders was 17-year-old "Domestic" Hannah E. Johnson (perhaps Emaline's younger sister?), and 8-month-old Margaret J. Sharp (perhaps Hannah's daughter?). Charles is not shown owning any value of real estate or personal property. Apparently, Charles was literate.

Charles Alexander's service records also tell us he was 34-years-old when he enlisted. He was only 5 feet 3.5 inches tall, and was described having a "brown" complexion. A note on one of his cards says that Alexander had a "varix" or varicose vein on his left leg. In February 1864, while stationed in Yorktown, Virginia, he spent time in a hospital.

The 22nd USCI participated in the June 15, 1864 attacks on Petersburg as part of Hincks' Division of the XVIII Corps. They fought at both Baylor's Farm and along the Dimmock Line of Confederate defenses ringing the Cockade City. It appears that he made it unscathed through those fights. However, in the weeks before their brigade was sent to Deep Bottom to prepare for the fight at New Market Heights they served in the earthworks near Petersburg. It was during this time, when on September 17, 1864, Pvt. Alexander was "killed . . . by explosion of a shell."

A list of last effects are not included among Pvt. Alexander's compiled service records, but his enlistment paper is. It confirms that he was literate, as his neat penmanship signature appears, written with a sure hand.

I cannot help but wonder, if and how, Emaline heard of her husband's death. How did she tell this heartbreaking information to her three children? By the time of his passing they would have been 10, 8, and 5, all old enough to realize their dear loss. Unfortunately, I was unable to find any of them in the 1870 census. However, in searches for Savila Alexander and Judge Burnsides Alexander, two of the couple's children, I located both. Savaila (later Valentine) died in 1944 at West Bradford, Chester County, Pennsylvania. Judge's 1920 death certificate shows he worked as a barber and lived in Bristol, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, and died of a kidney ailment.

I salute you Pvt. Charles Alexander. Rest in peace.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)