Sunday, March 31, 2013

Kentucky, the Union, and the Washington Monument

This stone was given by the state of Kentucky in 1850 to be included in the Washington Monument, then being constructed in Washington D.C. It reiterates the state's strident demand for Union at a time when the idea of secession was bantered about due to issues caused by the Mexican War, and the Compromise of 1850, which included provisions for the admission of California, and a strengthened Fugitive Slave Law.

The engraved stone includes an image of Kentucky's motto: "United We Stand, Divided We Fall." Under arching laurels is the inscription "Under the auspices of heaven, and the precepts of Washington, Kentucky will be the last to give up the Union."

For more images of stones contributed to the Washington Monument try this link.

Image courtesy of the National Park Service.

Thursday, March 28, 2013

The Malicious Stabbing of George Mukes

To learn about the troublesome atmosphere that pervaded Kentucky during the Reconstruction years, one does not have to look much beyond period newspapers. The following story ran in the February 25, 1870, edition of the Frankfort Commonwealth:

Malicious Stabbing

"On Wednesday evening last, while the colored convention was in session, a Negro named George Mukes was stabbed by Robert L. Henderson, a white citizen of this city, under the following circumstances: Henderson had been drinking and went to the Hall where the convention was being held, and ascending the steps and taking his stand at the door, he stabbed the first colored man who came out, which was Mukes. The stabbing was unprovoked, without cause and cruel. The wound inflicted was in the breast near the heart and is severe, if not a fatal one. Mukes was an industrious, inoffensive boy, and his attempted murder cannot call too loudly for the interposition of justice. Henderson was promptly arrested by the police and lodged in jail. This is not the first, but the second or third offense of the kind of which he has been guilty.

In this connection we subjoin, an illustration of local journalism, the following innocent account of the affair as given in yesterday's Yeoman. The reporters of the Yeoman were probably absent from the city and unable to procure accurate particulars of the affair:

'Yesterday afternoon, about half past 4 o'clock, a Negro, whose name we could not learn, was cut with a pocket knife in the hands of a white man, named Bob Henderson, under the following circumstances: Henderson, who had been drinking, was in front of Major Hall, and had out his knife, swinging his hand around, when the Negro came by, and was struck with it in the side, the blade inflicting quite a serious cut. Henderson was promptly arrested, and placed in jail'"

The incident, as the story mentions, happened at Major Hall, so named for Frankfort prominent citizen and leader, S.I.M. Major. The auditorium, sometimes called the Opera House seated 1500 and opened in 1869. It burned in 1882. The above picture shows the location on the south side of West Main Street where Major Hall once stood.

The story related that Mukes was industrious and inoffensive. Insensitively, it also called him a "boy," although he was about 30 years old in 1870. In that year's census Mukes is listed as a "laborer" and is in the household of Moses White. Mukes' wife Martha is listed as a domestic servant and is shown owning $800 real estate and personal property worth $150. In 1880 Mukes is listed as a "farm hand" and Martha is shown as a "washer woman."

Obviously, Mukes survived since he was listed on the 1870 census, which was taken in July; five months after the stabbing incident. And, since he was in the 1880 census, there must have not been long-term effects from the stabbing. It appears that Mukes lived on Hill Street in Frankfort (now gone due to urban renewal) and did not pass away until 1889.

So what was George Mukes' story before the stabbing. Of the records I could find, it appears that he was just as "industrious" as a slave and as a United States Colored Troops soldier as he was as a free man.

The enlistment and service papers for Mukes give a picture of the man. They show that he was 24 years old when he enlisted at Camp Nelson in Company E of 5th United States Colored Cavalry, on September 9, 1864. He was from Anderson County, and is shown as a "farmer," which I am sure is accurate, albeit a slave farmer. He was owned by Mr. Marion Lillard and apparently ran away as his service records do not indicate he signed up with the permission of his owner. Lillard is listed in the 1860 census as a 40 year old farmer and had $6000 in personal property. I was unable to locate Lillard on the 1860 slave schedule census, but I would guess he owned several slaves with such a large personal property worth. Lillard was located in the 1850 slave schedules. He owned 15 slaves at that time.

Mukes is described in his service records as "black," with black eyes and black hair. He is listed as five feet four inches tall. He is shown as "present" in every account, and was owed bounty money on some of the records. Mukes remained with the 5th USCC until the unit was mustered out of the service in Helena, Arkansas, on March 16, 1866.

Apparently, Mukes was buried in Frankfort's Greenhill Cemetery, where a number of his USCT comrades also rest. I made a search through the cemetery a couple of weeks ago looking for his marker but was unable to locate it. However, his name is proudly inscribed on the monument to Franklin County's African American Civil War soldiers. It is the 13th name from the bottom in the image below, which I took a couple of years ago on Memorial Day.

I was unable to find out the legal fate of Mukes' attacker, Robert Henderson. It appears though that if he served any time it was short, because he, too, is listed in the 1870 census, which was taken that July following the stabbing. Henderson is listed as a 27 year old laborer. It does not appear the he served in the Civil War, as although he is shown in Franklin County's draft registry as a 20 year old clerk, there was no indication that he ever enlisted.

Tuesday, March 26, 2013

Just Finished Reading: Divided Loyalties

I am always excited when a new book on Kentucky's Civil War history comes out. Until the past few years the Commonwealth's role in the war had been long ignored, but finally the Bluegrass State is receiving the scholarly attention it deserves.

James W. Finck's book, Divided Loyalties: Kentucky's Struggle for Armed Neutrality in the Civil War, fills a hole that has previously only been covered with scholarly articles - and many of those decades old.

Speaking with individuals around the state I am continually surprised by how many of them believe that Kentucky remained neutral throughout the entire war. I am not sure how that myth got started, but it has certainly proved persistent. I suppose much of its basis is in the fact that Kentucky was so divided, which is largely what Finck argues.

Finck, in Divided Loyalties, contends that the Bluegrass State did not support neutrality out of its steadfast commitment to the Union, but rather it was the state's deeply divided nature that led a declaration of neutrality. I would not necessarily disagree with that statement, but in arguing that Kentucky's division led to neutrality Finck argues that Kentucky was not as committed to the Union as once previously believed. Here, I would disagree.

The majority of Kentucky's citizens felt a deep attachment to the Union. An attachment that was fostered by the politics and example of Kentucky's premier statesman, Henry Clay. Clay's influence on the people of Kentucky was felt long after his death in 1852; something that Finck (in my opinion) did not explore deeply enough. Reading Kentucky newspapers during the secession crisis, during neutrality, and after declaring for the Union, one really gets the strong understanding that the state believed that the Union should survive. This sentiment was expressed in the articles, it was expressed in editorials, and it was even expressed in the advertisements. For instance, one businessman's 1861 ad I recently came across said that he had Colt revolvers for sale, but only to good Union men.

Finck brings up Kentucky's unique geographical location, its commitment to the institution of slavery, and how those realities influenced the state's path. However, I think more emphasis was needed here. Kentucky's commitment to the Union was strengthened by the understanding that if the state seceded they would not have the fugitive slave act as a means of regaining their property. In short, Kentucky felt slavery could best be preserved in the Union rather than out of it. Lincoln knew this and that is why the border states were exempt from the Emancipation Proclamation and why he allowed Kentucky to delay the recruitment of African Americans for the Union army. It was largely after these two major events that numerous Kentuckians started to reconsider its loyalty to Union: a nation that was now (1863-64) seemingly against its best interests.

In reading Divided Loyalties, I came unfortunately came across a number of inaccuracies. Some of them were probably nothing more than typos that should have been caught by an editor or the publisher's readers; others left me wondering how much other information in the book was flawed.

For example, in the "Introduction," on page xv, mention is made to the Mayville Convention. This was actually the Mayfield Convention, which was held in Graves County. Unfortunately, it is incorrectly called Mayville again later in the book and is listed that way in the index.

On the same page and onto the next page is the following quote: "These historians have suggested that Kentucky's loyalty can be proven by counting all the votes for [Stephen] Douglas, [Abraham] Lincoln, and [John J.] Crittenden as a vote for unconditional unionism and a vote for [John C.] Breckinridge as a vote for secession." I am not sure how this was missed! John J. Crittenden was certainly not a presidential candidate with the others in the 1860 election; it was John Bell.

On page 48, Finck discussed the new 1849-50 Kentucky constitution. Here, he claims, "In the end, the anti-slavery party won only nine percent of the vote. Consequently, the new constitution required that freed blacks leave the state." I could be wrong, but I am almost certain that freed blacks were not required to leave the state. When John Brown's raid happened nine years later, much discussion went on in the Kentucky legislature on this issue. If it was made a law in 1850, why would lawmakers consider making it a law again short of a decade later?

A number of times Finck mentions the importance of Fort Sumter and its significance in swaying states such as Virginia, North Carolina, Arkansas, and Tennessee out of the Union. However, from my previous readings, I have always believed that it was not so much the firing on Fort Sumter that prompted the change of mind in the people of those states, but rather it was Lincoln's call for 75,000 volunteers to put down the rebellion that caused citizens (and legislatures) to jump on the secession bandwagon. In my opinion, Finck doesn't emphasize this important point enough.

On page 87, Finck states, "However, Kentucky's Magoffin, like Arkansas' governor, eventually called for secession; yet he fully supported the peace measure." Now, I could be wrong again, but I have never come across a document that shows that Magoffin ever formally called for secession. Finck uses an article titled "The Real Cause Lost: The Peace Convention of 1861," by Howard Westwood as his source for this claim. I think a primary source would have been more solid evidence for such a claim.

Finally, on page 189, Finck misnames General McCook. He calls him Anson, but it was actually Anson's cousin, Alexander that made Union soldiers return runaway slaves to their masters.

One thing I did really appreciate about the book was the inclusion of transcribed primary source documents in the appendix. Governor Magoffin's correspondence with Alabama secession commissioner Stephen Hale is enlightening. The Republican, Constitutional Union, and Democratic Party platforms are also significant. As are Magoffin's neutrality declaration, and his messages to Presidents Lincoln and Davis (the one to Lincoln on page 227 is misdated as August 19, 1961).

Divided Loyalties covers a significant topic in Kentucky's history that has previously only received cursory attention. It contributes to a better understanding of how conflicted Kentucky was due to its geographic location, politics, economy, culture, and traditions. While I think certain arguments that the author advances are not always fully explored, it does cause one to reconsider previous interpretations. On a scale of one to five I give Divided Loyalties a four.

James W. Finck's book, Divided Loyalties: Kentucky's Struggle for Armed Neutrality in the Civil War, fills a hole that has previously only been covered with scholarly articles - and many of those decades old.

Speaking with individuals around the state I am continually surprised by how many of them believe that Kentucky remained neutral throughout the entire war. I am not sure how that myth got started, but it has certainly proved persistent. I suppose much of its basis is in the fact that Kentucky was so divided, which is largely what Finck argues.

Finck, in Divided Loyalties, contends that the Bluegrass State did not support neutrality out of its steadfast commitment to the Union, but rather it was the state's deeply divided nature that led a declaration of neutrality. I would not necessarily disagree with that statement, but in arguing that Kentucky's division led to neutrality Finck argues that Kentucky was not as committed to the Union as once previously believed. Here, I would disagree.

The majority of Kentucky's citizens felt a deep attachment to the Union. An attachment that was fostered by the politics and example of Kentucky's premier statesman, Henry Clay. Clay's influence on the people of Kentucky was felt long after his death in 1852; something that Finck (in my opinion) did not explore deeply enough. Reading Kentucky newspapers during the secession crisis, during neutrality, and after declaring for the Union, one really gets the strong understanding that the state believed that the Union should survive. This sentiment was expressed in the articles, it was expressed in editorials, and it was even expressed in the advertisements. For instance, one businessman's 1861 ad I recently came across said that he had Colt revolvers for sale, but only to good Union men.

Finck brings up Kentucky's unique geographical location, its commitment to the institution of slavery, and how those realities influenced the state's path. However, I think more emphasis was needed here. Kentucky's commitment to the Union was strengthened by the understanding that if the state seceded they would not have the fugitive slave act as a means of regaining their property. In short, Kentucky felt slavery could best be preserved in the Union rather than out of it. Lincoln knew this and that is why the border states were exempt from the Emancipation Proclamation and why he allowed Kentucky to delay the recruitment of African Americans for the Union army. It was largely after these two major events that numerous Kentuckians started to reconsider its loyalty to Union: a nation that was now (1863-64) seemingly against its best interests.

In reading Divided Loyalties, I came unfortunately came across a number of inaccuracies. Some of them were probably nothing more than typos that should have been caught by an editor or the publisher's readers; others left me wondering how much other information in the book was flawed.

For example, in the "Introduction," on page xv, mention is made to the Mayville Convention. This was actually the Mayfield Convention, which was held in Graves County. Unfortunately, it is incorrectly called Mayville again later in the book and is listed that way in the index.

On the same page and onto the next page is the following quote: "These historians have suggested that Kentucky's loyalty can be proven by counting all the votes for [Stephen] Douglas, [Abraham] Lincoln, and [John J.] Crittenden as a vote for unconditional unionism and a vote for [John C.] Breckinridge as a vote for secession." I am not sure how this was missed! John J. Crittenden was certainly not a presidential candidate with the others in the 1860 election; it was John Bell.

On page 48, Finck discussed the new 1849-50 Kentucky constitution. Here, he claims, "In the end, the anti-slavery party won only nine percent of the vote. Consequently, the new constitution required that freed blacks leave the state." I could be wrong, but I am almost certain that freed blacks were not required to leave the state. When John Brown's raid happened nine years later, much discussion went on in the Kentucky legislature on this issue. If it was made a law in 1850, why would lawmakers consider making it a law again short of a decade later?

A number of times Finck mentions the importance of Fort Sumter and its significance in swaying states such as Virginia, North Carolina, Arkansas, and Tennessee out of the Union. However, from my previous readings, I have always believed that it was not so much the firing on Fort Sumter that prompted the change of mind in the people of those states, but rather it was Lincoln's call for 75,000 volunteers to put down the rebellion that caused citizens (and legislatures) to jump on the secession bandwagon. In my opinion, Finck doesn't emphasize this important point enough.

On page 87, Finck states, "However, Kentucky's Magoffin, like Arkansas' governor, eventually called for secession; yet he fully supported the peace measure." Now, I could be wrong again, but I have never come across a document that shows that Magoffin ever formally called for secession. Finck uses an article titled "The Real Cause Lost: The Peace Convention of 1861," by Howard Westwood as his source for this claim. I think a primary source would have been more solid evidence for such a claim.

Finally, on page 189, Finck misnames General McCook. He calls him Anson, but it was actually Anson's cousin, Alexander that made Union soldiers return runaway slaves to their masters.

One thing I did really appreciate about the book was the inclusion of transcribed primary source documents in the appendix. Governor Magoffin's correspondence with Alabama secession commissioner Stephen Hale is enlightening. The Republican, Constitutional Union, and Democratic Party platforms are also significant. As are Magoffin's neutrality declaration, and his messages to Presidents Lincoln and Davis (the one to Lincoln on page 227 is misdated as August 19, 1961).

Divided Loyalties covers a significant topic in Kentucky's history that has previously only received cursory attention. It contributes to a better understanding of how conflicted Kentucky was due to its geographic location, politics, economy, culture, and traditions. While I think certain arguments that the author advances are not always fully explored, it does cause one to reconsider previous interpretations. On a scale of one to five I give Divided Loyalties a four.

Sunday, March 24, 2013

John P. Clark, Lexington African American Barber

Among the advertisements on page four of the October 19, 1861, edition of Lexington Observer and Reporter are ones for "Fresh Oysters," "Sayre Female School," "Slate Roofing," - and yes, "FOR SALE, A Negro Woman, 22 years old, a good seamstress, Cook, Washer and Ironer, and sold for no fault." Also among them is a listing announcing the movement of the barbershop of John P. Glark. (Apparently the typesetter got the spelling wrong; it is actually Clark.)

"Jno. P. Clark" was located in the 1870 census living in Ward Number 3 in Lexington. He is listed as a 52 years old black man whose occupation is "barber." It seems that he was literate. Living with John was his wife Catherine, a 39 year old mulatto woman who is described as "keeping house," and marked as illiterate.

Clark was not able to be located in the 1860 census. I supposed it is possible that he was still a slave the year before the advertisement ran and thus would not be listed by name, but that is merely speculation.

However, another interesting record on Clark survives. He is listed on the books of the Freedman's Savings Bank. This record provides a plethora of family information. This record dates from July 3, 1871, and states that Clark was born in Fayette County, Kentucky, was "brought up" in Lexington, and resided on Main Street. It listed his occupation as barber and that he worked for Alfred Rainey. Like the census record this record has Clark's wife as Catherine, but unlike the census, it lists Ellen Pope as a daughter, although no age is given for Ellen. She was probably an adult in when the census was taken, and thus with a different last name, was probably already married and living in another household.

Amazingly, the Freedman's Savings Bank record also lists Clark's parents, Tumbler and Rhoda Clark; as well as his brother Robert, and sisters Sally and Martha. This document also contains Clark's signature, proving what the census record indicated - that he was literate.

What a wonderful genealogy tool this would prove to be for someone searching Clark's tree.

Friday, March 22, 2013

Cutting Box

In my post yesterday about a runaway slave advertisement, I inquired what type of instrument a cutting box might have been. After doing some searching online, I think I finally have an answer - and I can see how someone could get their hand or fingers caught in it and do some serious damage, as the advertisement mentioned about the runaway slave.

The idea behind the utility of this implement is to feed fodder (usually corn stalks) through one end of the trough-like three-sided box. At the end of the box a sharp blade is attached that the operator raises and lowers, thus cutting the fodder into sizable portions that farm animals can then safely consume.

Here is a video of a cutting box in operation. History mystery solved!

Thursday, March 21, 2013

RANAWAY -

Doing some recent research on slavery advertisements in Kentucky newspapers during the Civil War I ran across the above ad in the Lexington Observer and Reporter. It was printed in the October 19, 1861 edition.

It is not especially unique as far as the runaway advertisements go, but I am curious about part of the slave's physical description. It says "Two of his fingers on his left hand are slightly contracted from having been caught in a cutting box."

Does anyone know what type of implement this is referring to? Does this have to do with some skilled trade or some agricultural tool? If anyone knows, I would certainly be interested to hear from you.

Wednesday, March 20, 2013

Just Finished Reading - African American Faces of the Civil War

I mentioned a few weeks back in one of my posts that I thought Facebook was proving more and more to be an excellent place to find out about what is going on in the field of history. In addition, it seems that more and more publishers and authors are using the social media giant to market their books. I am sure this not surprising to anyone since the whole idea of Facebook anyway is to make connections and share information.

On Facebook I noticed that several friends had "liked" Ronald S. Coddington and his series of "Faces" books. Intrigued, I checked into them on Amazon.com and found a used but clean copy of African American Faces of the Civil War: An Album.

African American Faces of the Civil War is one of those books that is difficult to put down when you crack it open. The basis of the book is a group of 77 photographic images, gathered from diverse locations and of mainly of the carte de visite and tintypes formats of African Americans - civilians, servants, slaves, and soldiers - and the stories of the men in those images.

Two African American regiments that were distinctly different get significant attention in the book. Eleven soldiers from the famous 54th Massachusetts Infantry get covered, while ten men from the 108th United States Colored Infantry are examined. While the 54th Massachusetts was composed largely of Northern free men of color, the 108th USCI was made up mainly of former slaves from Kentucky. It is not surprising that many photographs of the 54th would remain extant since they have been remembered well in history for their battlefield exploits. However, for a unit like the 108th, which saw relatively little combat and spent much of their time in garrison and prison duty, having so many photographs come to light is a real treat. Fortunately, an officer of the 108th kept a large number of images of the men that served under him and annotated each one.

I was pleased to find that a great many of the men profiled in African American Faces had Kentucky connections. That only makes since, as the Bluegrass State provided more USCT soldiers than any other state except Louisiana.

Coddington went to great lengths to tell these men's stories. He utilized their service and pension records, but also researched state and local history repositories to provide the accurate backgrounds, war records, and post war years that the men lived and experienced. And, while many of the men struggled through similar trials and tribulations due to their backgrounds, all also had unique facets to their lives.

As previously mentioned, African American Faces of the Civil is a real page-turner. You will not be disappointed with this book. I highly recommend it and would suggest that it be required reading for any Civil War enthusiast - especially during the current Sesquicentennial. On a scale from one to five, I give it a full five.

I have ordered Coddington's Faces of the Confederacy: An Album of Southern Soldiers and Their Stories and am looking forward to reading it as soon as it arrives. If it is half as interesting as African American Faces I will be pleased.

On Facebook I noticed that several friends had "liked" Ronald S. Coddington and his series of "Faces" books. Intrigued, I checked into them on Amazon.com and found a used but clean copy of African American Faces of the Civil War: An Album.

African American Faces of the Civil War is one of those books that is difficult to put down when you crack it open. The basis of the book is a group of 77 photographic images, gathered from diverse locations and of mainly of the carte de visite and tintypes formats of African Americans - civilians, servants, slaves, and soldiers - and the stories of the men in those images.

Two African American regiments that were distinctly different get significant attention in the book. Eleven soldiers from the famous 54th Massachusetts Infantry get covered, while ten men from the 108th United States Colored Infantry are examined. While the 54th Massachusetts was composed largely of Northern free men of color, the 108th USCI was made up mainly of former slaves from Kentucky. It is not surprising that many photographs of the 54th would remain extant since they have been remembered well in history for their battlefield exploits. However, for a unit like the 108th, which saw relatively little combat and spent much of their time in garrison and prison duty, having so many photographs come to light is a real treat. Fortunately, an officer of the 108th kept a large number of images of the men that served under him and annotated each one.

I was pleased to find that a great many of the men profiled in African American Faces had Kentucky connections. That only makes since, as the Bluegrass State provided more USCT soldiers than any other state except Louisiana.

Coddington went to great lengths to tell these men's stories. He utilized their service and pension records, but also researched state and local history repositories to provide the accurate backgrounds, war records, and post war years that the men lived and experienced. And, while many of the men struggled through similar trials and tribulations due to their backgrounds, all also had unique facets to their lives.

As previously mentioned, African American Faces of the Civil is a real page-turner. You will not be disappointed with this book. I highly recommend it and would suggest that it be required reading for any Civil War enthusiast - especially during the current Sesquicentennial. On a scale from one to five, I give it a full five.

I have ordered Coddington's Faces of the Confederacy: An Album of Southern Soldiers and Their Stories and am looking forward to reading it as soon as it arrives. If it is half as interesting as African American Faces I will be pleased.

Tuesday, March 19, 2013

Henry Samuel, Frankfort Barber and Free Man of Color

Recently reading Knights of the Razor: Black Barbers in Slavery and Freedom got me to wondering if Frankfort had any black barbers in the antebellum era. Well, I didn't have to look too hard to find one. No, I didn't have to search through slides of microfilm searching the 1860 census records for Franklin County barbers - after all, in this particular case that would not have helped me.

Fortunately, I had remembered seeing an advertisement for a town barber while browsing through issues of the Frankfort Commonwealth newspaper some time back. And, it was not difficult to find these particular advertisements when I went back searching, because Henry Samuel had an ad in almost every edition of the newspaper for many years in the 1850s and 1860s. He must have been a firm believer in the old adage that "advertising pays." However, there was no clue from the advertisements whether he was African American or white. That part took some searching.

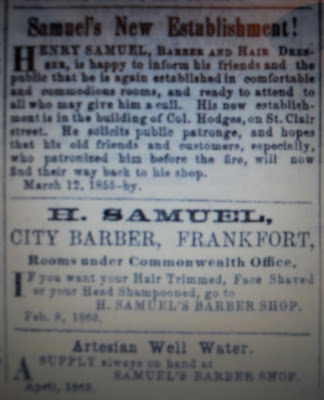

The three-section advertisement above was published in the August 19, 1862 edition of the Daily Commonwealth. The first part reads:

"Samuel's New Establishment! Henry Samuel, Barber and Hair Dresser, is happy to inform his friends and the public that he is again established in comfortable and commodious rooms, and ready to attend to all who may give him a call. His new establishment is in the building of Col. Hodges, on St. Clair street. He solicits public patronage, and hopes that his old friends and customers, especially who patronized him before the fire, will now find their way back to his shop." This part of the ad is dated March 17, 1855, and mentions the fire that burned his old shop and other buildings in 1854.

The second part of the ad reads: "H. SAMUEL, CITY BARBER, FRANKFORT, Rooms under Commonwealth Office. If you want your Hair Trimmed, Face Shaved or Head Shampooed, go to H. SAMUEL'S BARBER SHOP." This section is dated Feb. 9, 1860.

The third part reads: Artesian Well Water. A SUPPLY always on hand at SAMUEL'S BARBER SHOP," and is dated April 1860. Apparently he ran these ads so often the newspaper kept the type set for future uses.

|

| "A Barbershop at Richmond, Virginia" |

A search for Samuel in the 1860 census found him listed as a 37 year old black man. Interestingly, the 1860 census did not list his occupation or his personal property or real estate worth. He was living with his wife Mary, who was 33 years old and identified as a mulatto. Also listed are his daughter Maria (15, mulatto), son Thomas (13, mulatto), a Alfred Hardin (17, mulatto) and a Minerva Wilkerson (60, mulatto), who may have been - I guessed - Samuel's mother-in-law, but I'm certainly not positive.

Henry Samuel is listed, too, in the 1850 census. Here he is shown as a 30 year old black man and his occupation is designated as a barber. Intriguingly, Mary, Maria, and Thomas are all listed as black, unlike the 1860 census census, which described them as mulatto. Also, listed in the family is a one-year-old with the unique name Barber Samuel. The infant Barber must not have survived childhood since he was not listed in 1860. Included in the household was 18 year old mulatto John Burbridge, who is also listed as a barber, and was likely an apprentice to Henry Samuel in his shop. Lastly is listed 68 year old Rosanna Hickman. Like Minerva Wilkerson in the 1860 census, I'm not certain who this extended family member might be.

Henry Samuel was found in the 1840 census also. There, he is listed as a single free man of color.

Henry Samuel must have benefited greatly from locating his shop where he did. Being in the office of one of the town's most distinguished newspapers, where politicians surely came to get the latest information - and within a block of the State Capitol building - must have put him in contact with many of the state's most wealthy and powerful men of that era. Certainly many were his customers.

As Samuel's advertisement indicates he was on the ground floor "under the Commonwealth Office" on St. Clair Street. The above image shows the old Frankfort Commonwealth newspaper building in the late-nineteenth or early- twentieth century when it served as the Stehlin furniture store.

The same building is shown above as it appears today. It was most recently the Marcus furniture store. The owner of the store bricked in the windows and painted the brick to look like window openings.

It is amazing to think that 150 years ago a walk by this location would have probably brought one into company with Kentucky's most influential individuals. The political strategy discussions that probably occurred in Henry Samuel's barbershop as the nation moved toward Civil War and as Kentucky weighed its considerations must have been thrilling. Additionally, the inside information that Samuel must have overheard and carried back to his African American friends and neighbors surely provided some advantages that most other slaves and free blacks simply did not have.

George H. Stehlin Building image courtesy of Russ Hatter and the Capital City Museum.

Monday, March 18, 2013

Paul Laurence Dunbar's USCT Connection

Noted African American poet Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872-1906) left a lasting legacy in his brief thirty-three years on this earth. His amazing poems brought him a recognition that few black men could accomplish during the era in which he lived. His artistic accomplishments are commemorated in the numerous streets in black neighborhoods and historically African American schools that are named in his honor. Not known though to most people who recognize his name, is his connection to the United States Colored Troops.

Dunbar was born in Dayton, Ohio, to Joshua and Matilda Burton Murphy Dunbar. Joshua, born probably in the 1820s, had been a skilled slave plasterer in Kentucky, but made his escape to Canada before the Civil War. When African Americans were finally allowed to join the fight in 1863, Joshua joined the 55th Massachusetts Infantry, the sister unit to the famous 54th Massachusetts. He was apparently given a medical discharge from the 55th, but soon enlisted in the 5th Massachusetts Cavalry (another black unit) where he attained the rank of sergeant. Joshua served with the 5th until the end of the war, and mustered out in Clarksville, Texas, in October 1865.

After his service, Joshua moved to Dayton, Ohio, where he met and married Matilda, a former Kentucky slave from Shelby County. They married in 1871, and Paul was born the following year. Unfortunately, Joshua and Matilda's relationship was not a happy one. They apparently separated in 1873 and divorced in 1876. Joshua died of pneumonia in 1885 and was buried at the Soldier's Home in Dayton.

Paul began writing at an early age and took advantage of Dayton's public schools. He was the only African American in his high school class. Unable to attend college, a former teacher helped Paul publish his first collection of poetry, titled Oak and Ivy. Continued writing brought more acclaim and Dunbar moved to Washington D.C., where he met and married Alice Ruth Moore in 1898. The following year Paul was diagnosed with tuberculosis. Self medicating with alcohol, he became addicted, which ruined his marriage. Paul lived the last few years of his life in Dayton, where he passed away in 1906.

One of Paul Laurence Dunbar's poems, "The Colored Soldiers," honors those African American Civil War fighting men who served the United States; like his father.

Dunbar was born in Dayton, Ohio, to Joshua and Matilda Burton Murphy Dunbar. Joshua, born probably in the 1820s, had been a skilled slave plasterer in Kentucky, but made his escape to Canada before the Civil War. When African Americans were finally allowed to join the fight in 1863, Joshua joined the 55th Massachusetts Infantry, the sister unit to the famous 54th Massachusetts. He was apparently given a medical discharge from the 55th, but soon enlisted in the 5th Massachusetts Cavalry (another black unit) where he attained the rank of sergeant. Joshua served with the 5th until the end of the war, and mustered out in Clarksville, Texas, in October 1865.

After his service, Joshua moved to Dayton, Ohio, where he met and married Matilda, a former Kentucky slave from Shelby County. They married in 1871, and Paul was born the following year. Unfortunately, Joshua and Matilda's relationship was not a happy one. They apparently separated in 1873 and divorced in 1876. Joshua died of pneumonia in 1885 and was buried at the Soldier's Home in Dayton.

Paul began writing at an early age and took advantage of Dayton's public schools. He was the only African American in his high school class. Unable to attend college, a former teacher helped Paul publish his first collection of poetry, titled Oak and Ivy. Continued writing brought more acclaim and Dunbar moved to Washington D.C., where he met and married Alice Ruth Moore in 1898. The following year Paul was diagnosed with tuberculosis. Self medicating with alcohol, he became addicted, which ruined his marriage. Paul lived the last few years of his life in Dayton, where he passed away in 1906.

One of Paul Laurence Dunbar's poems, "The Colored Soldiers," honors those African American Civil War fighting men who served the United States; like his father.

The Colored Soldiers

If the muse were mine to tempt it

And my feeble voice were strong,

If my tongue were trained to measures,

I would sing a stirring song.

I would sing a song heroic,

Of those noble sons of Ham,

Of the gallant colored soldiers

Who fought for Uncle Sam.

In the early days you scorned them,

And with many a flip and flout

Said "These battles are the white man's,

And whites will fight them out."

Up the hills you fought and faltered,

In the valleys you strove and bled,

While your ears still hear the thunder

Of the foes' advancing tread.

Then distress fell on the nation,

And the flag was drooping low;

Should the dust pollute your banner?

No! the nation shouted, No!

So when War, in savage triumph,

Spread abroad his funeral pall--

Then you called the colored soldiers,

And they answered to your call.

And like hounds unleashed and eager,

For the life blood of the prey,

Spring they forth and bore them bravely

In the thickest of the fray.

And where'er the fight was hottest,

Where the bullets fastest fell,

There they pressed unblanched and fearless

At the very mouth of hell.

Ah, they rallied to the standard

To uphold it by their might;

None were stronger in their labors,

None were braver in the fight.

From the blazing beach of Wagner

To the plains of Olustee,

They were the foremost in the fight

Of the battles of the free.

And at Pillow! God have mercy

On the deeds committed there,

And the souls of those poor victims

Sent to Thee without a prayer.

Let the fullness of Thy pity

O'er the hot wrought spirits sway

Of the gallant colored soldiers

Who fell fighting on that day!

Yes, the Blacks enjoy their freedom,

And they won it dearly too;

For the life blood of their thousands

Did the southern fields bedew.

In the darkness of their bondage,

In the depths of slavery's night,

Their muskets flashed the dawning,

And they fought their way to light.

They were comrades then and brothers,

Are they more or less to-day?

They were good to stop the bullet

And to front the fearful fray.

They were citizens and soldiers,

When rebellion raised its head;

And the traits that made them worthy, -

Ah! those virtues are not dead.

They have shared your nightly vigils,

They have shared your daily toil;

And their blood with yours comingling

Has enriched the Southern soil.

They have slept and marched and suffered

'Neath the same dark skies as you,

They have met as fierce a foeman,

And have been as brave and true.

And their deeds shall find a record

In the registry of Fame;

For their blood has cleansed completely

Every blot of Slavery's shame.

So all honor and all glory

To those noble sons of Ham--

The gallant colored soldiers

Who fought for Uncle Sam!

Sunday, March 17, 2013

Just Finished Reading - Knights of the Razor

Nearly three years ago I posted about a letter I found from a free man of color and black barber named Abraham Meaux to Kentucky governor Beriah Magoffin concerning matters in the state during the wake of John Brown's raid. As a result I was highly intrigued to learn more about free blacks' occupational choice as barbers.

In my leisure reading I often came across references to both slave and free barbers. Of special significance was the diary of black barber William Johnson. But, I was pleased to finally get a copy of Knights of the Razor: Black Barbers in Slavery and Freedom by Douglas Walter Bristol, Jr. through my local library on interlibrary loan.

Bristol explains that blacks - especially slaves - came to be barbers mainly due to whites' reluctance to possess occupations that hinted at servitude. Whites often associated their citizenship with independence, and those that served others could not be considered truly independent. Ironically, the barbering trade allowed some blacks - slaves and a number of free men of color - the opportunity to purchase independence (either their freedom or acquire property). Since few white men in the antebellum era, especially in the South, would consider cutting hair and shaving other white men as an honorable occupation, barbering allowed black men the chance to "prosper without inspiring white animosity."

Barbering also allowed blacks the chance to help fellow African Americans. Many of those that established their own shops hired other young black men as apprentices, thus giving them the opportunity to learn the trade in a relatively supportive environment. But, in some instances, black barbers' attempts to obtain even more white patrons and advance ever so slowly in society, led some to distance themselves from other blacks of lower social status. For most though, as Bristol explains, "Black barbers led a double life. In their first-class barbershops, they conformed to the stereotyped roles dictated by their white customers, even as in their communities, they led and inspired others."

One thing that Bristol brings out, and that fits perfectly with the letter I found by Meaux to Gov. Magoffin, is that "free African Americans turned to white patrons for protection." In the case of Meaux, he was concerned that free blacks such as himself would be removed from Kentucky due to white fears that they would support a John Brown-style operation in the Bluegrass state. Meaux wanted to reassure the governor that he had no such sentiments and that he earned his keep through hard work. Bristol explains that due to their unique position, black barbers often served as the bridge between the black and white communities, settling misunderstandings and resolving touchy issues.

As the nation moved toward Civil War, black barbers were already being squeezed out of their previously secured positions. Immigrants from Ireland, Italy, and Germany increasingly came to the United States with barbering skills and without the servitude hangups that native whites possessed. During Reconstruction, the last part of the nineteenth, and first part of the twentieth century, as white and black society segregated more formally, whites increasingly sought out whites and black increasingly sought out blacks to cut their hair, shave their faces, and to serve as social centers for the exchange of community information and ideas.

I highly recommend Knights of the Razor: Black Barbers in Slavery and Freedom. The analysis that Bristol provides on this subject and the evidence that he marshals is impressive. He has put together a fine book that is not only highly readable, but one that contributes significantly to our understanding of the antebellum African American world. On a scale of one to five, I give it a 4.75.

In my leisure reading I often came across references to both slave and free barbers. Of special significance was the diary of black barber William Johnson. But, I was pleased to finally get a copy of Knights of the Razor: Black Barbers in Slavery and Freedom by Douglas Walter Bristol, Jr. through my local library on interlibrary loan.

Bristol explains that blacks - especially slaves - came to be barbers mainly due to whites' reluctance to possess occupations that hinted at servitude. Whites often associated their citizenship with independence, and those that served others could not be considered truly independent. Ironically, the barbering trade allowed some blacks - slaves and a number of free men of color - the opportunity to purchase independence (either their freedom or acquire property). Since few white men in the antebellum era, especially in the South, would consider cutting hair and shaving other white men as an honorable occupation, barbering allowed black men the chance to "prosper without inspiring white animosity."

Barbering also allowed blacks the chance to help fellow African Americans. Many of those that established their own shops hired other young black men as apprentices, thus giving them the opportunity to learn the trade in a relatively supportive environment. But, in some instances, black barbers' attempts to obtain even more white patrons and advance ever so slowly in society, led some to distance themselves from other blacks of lower social status. For most though, as Bristol explains, "Black barbers led a double life. In their first-class barbershops, they conformed to the stereotyped roles dictated by their white customers, even as in their communities, they led and inspired others."

One thing that Bristol brings out, and that fits perfectly with the letter I found by Meaux to Gov. Magoffin, is that "free African Americans turned to white patrons for protection." In the case of Meaux, he was concerned that free blacks such as himself would be removed from Kentucky due to white fears that they would support a John Brown-style operation in the Bluegrass state. Meaux wanted to reassure the governor that he had no such sentiments and that he earned his keep through hard work. Bristol explains that due to their unique position, black barbers often served as the bridge between the black and white communities, settling misunderstandings and resolving touchy issues.

As the nation moved toward Civil War, black barbers were already being squeezed out of their previously secured positions. Immigrants from Ireland, Italy, and Germany increasingly came to the United States with barbering skills and without the servitude hangups that native whites possessed. During Reconstruction, the last part of the nineteenth, and first part of the twentieth century, as white and black society segregated more formally, whites increasingly sought out whites and black increasingly sought out blacks to cut their hair, shave their faces, and to serve as social centers for the exchange of community information and ideas.

I highly recommend Knights of the Razor: Black Barbers in Slavery and Freedom. The analysis that Bristol provides on this subject and the evidence that he marshals is impressive. He has put together a fine book that is not only highly readable, but one that contributes significantly to our understanding of the antebellum African American world. On a scale of one to five, I give it a 4.75.

Thursday, March 14, 2013

Zooming in on USCT Soldiers at Rest

At first glace the photograph above looks like so many others of Civil War soldiers lounging about. But, a closer, zoomed-in look shows details otherwise unobserved. This rare image actually shows a group of about 40 United States Colored Troops soldiers at Aiken's Landing on the James River in Virginia.

This soldier sits on the bank with his haversack and tin cup on his lap. He sports an unusual knit cap and may be wearing gloves.

Another soldier lounges with a full knapsack and blanket roll wrapped in a rubber ground cover. It also appears that he is wearing mittens.

This soldier is wearing an army greatcoat and either a vest or shell jacket under it. Like a number of the other soldiers, he is wearing a slouch hat rather than a regulation forage cap.

An interesting thing about this particular photograph is that only a small number of the men have their weapons near. The others must have stacked their rifles somewhere outside of the image's scope. The forward soldier has his rifle by his right side and appears to be wearing a sky blue greatcoat cape with a navy frock coat. His haversack, canteen, and tin cup rest on his left side. The soldier resting behind seems to be supported by his knapsack and has his arms folded across a full haversack on his stomach. He has his slouch hat pulled down to shade his eyes from the sun.

A group of five soldiers appear on the right side of the photograph. Three wear forage caps and two wear slouch hats. They all seem to be well equipped like their comrades. A white fence runs behind them and a barrel rests near.

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress. The TIFF file can be downloaded here.

Wednesday, March 13, 2013

What's Up with Salt River and Antebellum Political Cartoons?

If you spend any appreciable time viewing antebellum political cartoons, you are likely to run into mentions of Salt River. But, where is this Salt River and why was it used so often by period cartoonists?

Salt River is an actual geographical feature of the state of Kentucky. It runs 150 winding miles from central Kentucky and empties into the Ohio River in Hardin County, just south of Louisville.

So, how did it come to be associated with politics - especially presidential candidates? There are several stories that explain the relationship between the river and the nation's highest office, but one stands out. The legend goes, that on a trip up the Ohio River, a Democratic boatman purposely delayed Whig presidential candidate Henry Clay from reaching a speaking engagement in Louisville by going up Salt River; thereby costing Clay an opportunity to gather valuable votes, and thus he lost the election.

Whatever may be the true story, political cartoonists took the analogy and ran wild with it, especially in the 1840s and 1850s. "Going up Salt River" became synonymous with reaching political oblivion; as the following cartoons show. Title links are supplied below each image for more information and interpretation by the Library of Congress.

Tuesday, March 12, 2013

Just Finished Reading

When I travel I seem to read even more than normal. What better way to pass the time while waiting in the airport or in the air? O.K., sure, there a plenty more things to do to whittle the hours away, but reading works for me.

A recent trip helped me complete a few books, so I thought I'd do a three for one post, covering those titles.

Over the past 12 years or so memory studies have probably dominated Civil War genres as much as anything. David Blight's trailblazing Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (2001) has spawned a whole library of followers. I have read many of these latter-day studies, but many have left me unimpressed. Not so with Cities of the Dead: Contesting the Memory of the Civil War in the South, 1865-1914, (2004) by William Blair.

In Cities of the Dead, Blair compares and contrasts white Southerners' Confederate Decoration Day ceremonies to black Southerners' Emancipation Day celebrations. As one might imagine these conflicting memories of the Civil War and its ultimate effects led to many contentious confrontations.

Blair contends that both groups used their own individual commemorations to promote their political goals: whites for redemption of their state governments from black and Federal military rule, and blacks for increased civil, political, and economic rights.

I would have appreciated a more full study, as this rather this slim volume (207 pages of text) covers largely commemorations in Virginia and leaves much of the rest of the South silent. So much so that the author's subtitle is somewhat misleading. But, with that minor gripe aside this is a fine book that everyone observing the Civil War's Sesquicentennial should read. On a scale from one to five, I give Cities of the Dead a 4.75.

If you read my posts often, you have probably figured out that I am a huge social history fan. Topics that many of us do not think about as being open to historical studies at first look, often turn out to be some of the best. For example, the recently published Routes of War, by Yael Sternhell, examines the role of movement in the Civil War South. Of course movement was important during the Civil War, but until someone thought to examine it, it remained in the dark. Similarly, Mark M. Smith's, Mastered by the Clock: Time, Slavery and Freedom in the American South (1997) sheds light on a topic of great significance, but previously unexplored.

In Mastered by the Clock, Smith shows that although the antebellum Southern states are often thought of as premodern societies ruled by seasonal and diurnal conceptions of time, they actually developed into clock-ruled regions, much like neighbors to the north.

Smith incorporates an impressive amount of primary source research to show that Southern masters came to accept clock-based time to instill a great efficiently with their slave labor in planting, cultivating, and harvesting their crops. And, while slave were not often allowed to own timepieces, plantations incorporated modes of time telling such as bells and horns to regulate slave time.

Much of white Southerners' acceptance of clock time and rejection of sun or seasonal time came from increased exposure and use of period services and inventions, including the postal/express service, steamboat, telegraph, and railroad - all of which ran on timed schedules.

Smith, too, explains that not all white Southerners thought clock-timed life was a good thing. Some believed that greater reliance on the timepiece had the potential to instill Yankee ideals and subvert their distinctive easy and leisurely Southern way of life.

Mastered by the Clock is a fascinating read and a thought-provoking look at a too little examined facet of antebellum Southern life. I highly recommend it those interested in understanding the changes the South experienced in the nineteenth century. On a scale of one to five, I give it a 4.75.

I have enjoyed all of the books I have ready by Stanley Harrold. His, Border War: Fighting over Slavery before the Civil War is a book that shouldn't be missed, and, The Abolitionists and the South, 1831-1861, is an important work too. Harrold continues his strong batting average with The Rise of Aggressive Abolitionism: Addresses to the Slaves (2004).

In this work, Harrold looks at the significance of three speeches in the 1840s by abolitionists Gerrit Smith, William Lloyd Garrison, and Henry Highland Garnet. These speeches - for the first time - sought the assistance of those held as slaves to help end the institution.

Harrold explains that contemporary events such as the Amistad and Creole ship insurrections, as well as greater numbers of successful escapes, led abolitionists to the conclusion that the enslaved were the great untapped reserve to immediately end slavery.

While the three speeches were toned so as to avoid violence on the part of the slaves, their intent is certainly to do something for themselves to help end their bondage. Previously abolitionists had largely thought of slaves as being only the benefactors of the antislavery societies work, but the three addresses showed a distinctive shift in the belief in the power of moral suasion to a greater reliance on slave empowerment. This movement would eventually lead to individuals like John Brown and taking the abolitionist fight to enemy territory.

I appreciated that Harrold not only includes his insightful analysis of the three addresses, but also has them in full text in the book's appendix, along with a couple of other related documents.

The Rise of Aggressive Abolitionism is an important study for better understanding the many facets of the antislavery cause. On a scale of one to five, I give it a 4.5.

Wednesday, March 6, 2013

Jarman, a Slave, the Property of Thos. Reynolds

In my February 6 post I remarked about a newspaper advertisement in 1864 offering a reward for the capture of a slave named Rial, who was accused of killing a man. In that post I speculated that the man that was killed might have been a slave since I could not find him in the census. But, I also mentioned that that victim was not noted as a slave in the advertisement, which seemed strange to me.

I now think the man was not another slave. I believe that to be the case because I recently found another reward advertisement (albeit earlier) for a slave killing a fellow slave. In this ad the victim is specifically noted as a slave.

This ad was in the February 15, 1856 edition of the Frankfort Commonwealth. It read in part:

"Proclamation by the Governor $100 Reward

In the name and by the authority of the Commonwealth of Kentucky.

Whereas, it has been represented to me that Jarman, a slave, the property of Thos. Reynolds, Esq., in September 1855, did, in Jessamine county, Kentucky kill and murder Horace, a slave, and is now going at large.

Now, therefore, I , Charles S. Morehead, Governor of said Commonwealth, do hereby offer a reward of One Hundred Dollars for the apprehension of the said Jarman, and his delivery to the jailer of Jessamine county within a year from this date."

After additional technical language the ad provided a description of the alleged murderer. "Jarman is about 30 years old, about six feet high and dark complexion."

I have not had an opportunity to look up owner Thomas Reynolds of Jessamine County. I am curious to find out more about him, such as his personal worth and how many slaves he owned, especially since the suffix Esquire is used. I would also be curious to know if Horace also belonged to Reynolds or someone else. Of course, the census slave schedules would not list the Reynolds slaves' names, so much deeper digging would be necessary to find this out.

Gov. Charles S. Morehead image courtesy of the Kentucky Historical Society.

I now think the man was not another slave. I believe that to be the case because I recently found another reward advertisement (albeit earlier) for a slave killing a fellow slave. In this ad the victim is specifically noted as a slave.

This ad was in the February 15, 1856 edition of the Frankfort Commonwealth. It read in part:

"Proclamation by the Governor $100 Reward

In the name and by the authority of the Commonwealth of Kentucky.

Whereas, it has been represented to me that Jarman, a slave, the property of Thos. Reynolds, Esq., in September 1855, did, in Jessamine county, Kentucky kill and murder Horace, a slave, and is now going at large.

Now, therefore, I , Charles S. Morehead, Governor of said Commonwealth, do hereby offer a reward of One Hundred Dollars for the apprehension of the said Jarman, and his delivery to the jailer of Jessamine county within a year from this date."

After additional technical language the ad provided a description of the alleged murderer. "Jarman is about 30 years old, about six feet high and dark complexion."

I have not had an opportunity to look up owner Thomas Reynolds of Jessamine County. I am curious to find out more about him, such as his personal worth and how many slaves he owned, especially since the suffix Esquire is used. I would also be curious to know if Horace also belonged to Reynolds or someone else. Of course, the census slave schedules would not list the Reynolds slaves' names, so much deeper digging would be necessary to find this out.

Gov. Charles S. Morehead image courtesy of the Kentucky Historical Society.

Monday, March 4, 2013

Election of 1860, John Bell, Constitutional Union Party

Probably the least historically remembered of the four candidates for president of the United States in the 1860 election is John Bell. The Tennessean ran on the Constitutional Union ticket, largely made up of old line Whigs. His running mate was Edward Everett of Massachusetts, who was a premier orator of the day, and is best remembered as the speaker that preceded Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address.

Bell and Everett did not fare very well in the 1860 race. Not surprisingly, the Constitutional Union ticket proved most popular in the upper-South, where Whigs had largely dominated in past elections. The pair won Kentucky, Virginia, and Bell's home state of Tennessee. But, of the four candidates, Bell brought in the least amount of votes, both in percentage and in popular votes.

Bell remained loyal to the Union during the secession crisis, but when Tennessee left the Union, he switched his support the Confederacy. When Nashville was captured by Union forces in the spring of 1862 he left the state. Bell returned to Tennessee home after the war and died at his Stewart County home in 1869.

All images courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Saturday, March 2, 2013

Rolling the Dice in Mexico

In any war, soldiers will be soldiers. And, in most wars soldiers will gamble - sometimes to make up for poor pay and sometimes just to pass the time. Of course, there are many ways to gamble. Some games require cards, but cards can get lost, or torn, or wet. Some gaming required horses, and some required roosters - both not always easy for the average soldier to obtain. But, one of the easiest games to carry and play on demand are dice. Dice could easily be made by soldiers just by carving cubes from wood, lead bullets, or even molding clay.

The unique die pictured above was carved by Kentucky soldier Benjamin D. Allan during his service in the Mexican War. It is carved from ivory and has the letters T-E-X-A-S, and an eight-point star (possibly the Lone Star?) each etched into the six sides.

It is fortunate that small pieces of material culture such as this die have survived to give us a better understanding of soldiers' experiences in Mexico.

Courtesy of the Kentucky Historical Society.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)