Tuesday, April 29, 2014

Monday, April 28, 2014

Black Barbers and their other Services

During the antebellum era Kentucky's African American barbers not only offered their customers the traditional haircut and shave, they also offered a variety of products and services in order to generate additional revenue.

For example, Frankfort barber Henry Samuel provided a bath house for his customers, which was open "from Monday to Sunday morning." Samuel also provided a laundry service at his shop. He claimed he had "the best kind of washer women," who could wash or scour customers' clothes clean quickly.

At various times Henry Samuel also advertised his hair coloring service. Although "Just for Men" had not been invented yet, apparently Samuel was adept at fighting gray hairs, whether found on the head or in the beard.

Samuel, too, offered artesian well water to customers. In an era plagued by waterborne diseases such as typhoid, dysentery, and cholera, fresh water - most often sold in glass demijohns - were popular in large towns and cities to those who could afford this luxury.

Nat Sims, who barbered in his own shop in Frankfort in the 1840s, and then at the shop in the Capital Hotel in the 1850s, advertised "Gilc[h]rist's fine Razors" in the above 1855 notice. I found it interesting that Sims would sell razors. After all, why sell a product that would potentially cut into (pun intended) your own business? Gilchrist's razors, which were manufactured in Jersey City, New Jersey, were the top of the line at the time. Perhaps Sims thought he could earn enough through razor sales that it made up for lost revenue in shaves.

Lexington black barber Daniel Fisher offered "Superior Eye Water." During the antebellum era various forms of hydrotherapy were thought to cure everything from arthritis and intestinal disorders to "sore eyes."

Much like Henry Samuel in Frankfort, Oleaginous Gordon in Bardstown offered a bathing service. Gordon's customers could visit his barber shop to get a "warm or cold bath" in either a tub or in a shower "at any time of the day or night." Appealing to those needing his service Gordon's ad text included a biblical reference: "All ye 'unwashed,' call and be cleansed."

These ads, which offered products and services outside of traditional barbering work, show the entrepreneurial spirit of the Kentucky's antebellum black barbers and their willingness to try to find additional means to generate revenue and thus profits for their businesses.

Wednesday, April 23, 2014

The Underground Railroad & Free Black Barbers

It seems that it was not unusual for free black barbers in Kentucky to assist runaway slaves. Georgia fugitive slave John Brown wrote about being helped by a Paducah barber. Louisville barber Washington Spradling both loaned money to slaves to buy their freedom and helped others make their way across the Ohio River to the free state of Indiana.

White Kentuckians' attitudes toward free African Americans were often influenced by stories such at that shown above. White citizens perceived that free blacks not only threatened their ordered slave society by being examples for slaves to aspire to, but also by assisting slaves in escaping from their servile situations.

This short article was printed in the June 30, 1855, edition of the Louisville Weekly Courier. It claims that Louisville free black barber, Theodore Sterrett, who was apparently "well-known" in the community, ran off to Canada after running up debts and borrowing money from friends. However, the last paragraph identifies a different or possibly additional reason for Sterrett leaving town. Sterrett, much like the other free barbers noted above, had a reputation for helping runaway slaves; possibly even encouraging them to abscond. Did Sterrett perhaps help a slave or group of slaves with the funds he allegedly borrowed, or did he possibly fear being caught and imprisoned after assisting an escape and thus make his was to Canada in effort to avoid be remanded?

It seems that Sterrett had a barber's position that provided for his family, and since he was "well-known," he likely had plenty of customers. The article indicates that Sterrett "packed his duds, his wife and other things" and made his way out of town under the cover of night. It does not say anything about the rest of his family. The 1850 census lists Sterrett as a 31 year old "mulatto" barber, who was born in Virginia. In his household was wife Ann, who was 23 years old, six year old son Don, four year old daughter Lurena, and two year old daughter Sarah. Did Sterrett leave his children behind in Louisville? Or, more likely, did the article just not mention them. In addition to the immediate family, three other individuals were listed in the Sterrett household: 10 year old Heston A. Ewing, 16 year old John Helton, and 14 year old George Helton. Did these boys make away with Sterrett and his family, too?

Regardless of the true details of this story, it provides a good example of how white attitudes toward free blacks were often shaped..

Monday, April 21, 2014

Frederick Douglass and Black Barbers

I found the short article pictured above in the January 29, 1855, edition of the Louisville Daily Democrat. Extremely brief articles of this type were quite common in mid-nineteenth century newspapers. They usually provided little in the way of significant news, were used to fill column space not occupied by advertisements or other real stories, and often attempted humor.

I am not sure whether this particular article has a truthful origin. Was the mixed-race Frederick Douglass refused service by a mixed-race barber in Biddeford, Maine? Honestly, it might be difficult or impossible to corroborate this story. I can confirm that the town of Biddeford, Maine, does exist, so at least that part was not made up. And, I would not be surprised to find that the rest of this incident did in fact occur. If it did, it provided perfect fodder for those wanting to denigrate Douglass, particularly those of the Democratic Party. Of course, Douglass made a career speaking out against slavery and attempting to bring equal rights to African Americans. What better way for his enemies to show Douglass in a bad light than to promote a story where he was not offered service by a "belubbed brudder" [beloved brother] black barber. Naturally, if the incident did occur, Douglass would have been disgusted with not being served. Douglass never felt below any man - white or black.

Interestingly, Douglass used his various publications to voice his thoughts on blacks in the barber profession. Douglass viewed barbering as a menial service occupation that reinforced both white and African American perceptions of blacks as being subservient, docile, and unmanly. In addition, Douglass believed that black barbers imitated their white patrons, and instead of helping their fellow African Americans, used their spare time for non-beneficial pursuits and their earnings for conspicuous consumption. Douglass once wrote in his newspaper, "To shave a half dozen faces in the morning, and to sleep or play the guitar in the afternoon - all this may be easy; but is it noble, is it manly, and does it improve and elevate us." Douglass also advised black parents to guide their sons away from service jobs such as waiters, porters and barbers. He saw that the barbers' time waiting on their next customer as that of being wasted and unproductive.

At least one black barber responded to Douglass' harsh treatment of his chosen profession. Uriah Boston, a black barber in Poughkeepsie, New York, claimed that he toiled in a respectable occupation that provided many black men with the opportunity to own their own business and thus elevate themselves and offer wages to their black barber employees.

Perhaps Douglass was speaking primarily of those black barbers he was familiar with in the free states where he lived, who though restricted in many ways, were still not as curbed as those that operated in the slave states. Douglass may not have fully appreciated the fact that free black barbers in the slave states used their occupation to gain a measure of independence that few other jobs there could offer or were even available. In addition, Douglass was likely unaware that free black barbers in the slave states sometimes owned their own business, accumulated both real and personal property, and in some instances - like Washington Spradling in Louisville - used their knowledge and earnings gained through servicing white patrons to assist slaves in making their escape or purchasing freedom.

Douglass image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Sunday, April 20, 2014

Slave Barber and Family for Sale

As one might expect, finding information on enslaved barbers here in Kentucky has been much more difficult than finding out about free men of color barbers. Due to obvious restrictions placed upon them traditional sources such letters, journals, and diaries are just plain rare if not nonexistent. However, some information has come to light though searching more unconventional source materials.

A while back I shared a captured runaway notice that advertised Jo Scott, who claimed to be a barber and had been caught in Trimble County, Kentucky. That ad also stated that Scott played the violin. Enslaved men who possessed additional skills were obviously more marketable than those that were unskilled.

The advertisement pictured above ran in the February 14, 1855, edition of the Lexington Observer and Reporter. The notice offered a five member family for sale. The father was listed as a good carriage driver, house servant, and barber. By noting all of the possible jobs that this man could hold, the seller naturally appealed to a broader audience of potential buyers. The purchaser could use this man as his personal driver or house slave, or could possibly hire him out to a local free man of color barber; the owner keeping part of the enslaved man's earned wages.

Along with the father of the family, the mother also possessed desirable experience in washing, ironing, and cooking. The oldest daughter (10 years old), too, was an experienced house servant. The other two children, were too young yet for much labor, but were potentially productive workers.

Sometimes ads such as these included language to the effect that the offered family was not to be broken up. Obviously, that was not the case here. If buyers desired only the skilled father, he could be separated from his wife and children. Or, if a trader preferred to purchase the children and not the parents, there was nothing that could be done to prevent their parting.

This harsh reality is one that resonated with abolitionists in an age of romanticism and one they capitalized on in both works of fiction, such as Uncle Tom's Cabin, and fact, such as narratives like Henry Bibb's.

Saturday, April 19, 2014

Black Barbers and the 1850 Kentucky Census

Well, today I finally finished going through all of the Kentucky counties in the 1850 census in my search for African American barbers. I did this for several reasons. First, I wanted to see where these men were primarily located. Knowing where they were will hopefully help me narrow down my search for even more of their newspaper advertisements. Second, I wanted to know what kind of property values they owned. Unfortunately, the 1850 census only gives real estate values. To get personal property values, one needs to search the 1860 census. Third, the 1850 census was the first census available that actually listed free persons' occupations. I am sure that in this census there were free men of color who were barbers but were either given a generic "laborer" for their occupation or were left totally blank for their profession. That is how it goes though, one just has to work with what one has.

There were a few neat things that turned up in my census search that I thought I'd share:

The oldest barber was 73 years old. His name was Doctor Perkins and he barbered in Augusta (Bracken County). He owned $400 in real estate.

The youngest, Seward Johnson, was 13. He was located in the 7th Ward of Louisville and was in either in the household or barber shop of Andrew Johnson, a 51 year old barber and possibly his father. It was interesting that Seward Johnson's occupation was given as the census form only asks for the occupations of males 15 years old and up. Other young barbers included: 16 year old Peter Mallery in Samuel A. Oldham's Lexington household; also in Lexington 17 year old Robert Taylor; 15 year old John Burney in Frankfort; 15 year old John Wilson and 17 year old Henry Hutchinson in Maysville; and, 17 year old Zachariah Mitchell in Bowling Green.

Not surprisingly, barbers were located in Kentucky's cities and towns. After all that is where the greatest customers were to be found. Having a barber shop in some rural outpost would just not have been good business sense. Suspected towns and cities such as Louisville (47 barbers), Lexington (9), and Frankfort (12) had the most barbers. Although Frankfort was less populated than Lexington, it likely had a few more barbers due to the fact that it was the state capital, and thus had a ready population that needed barbering services. Maysville had 8 barbers. Most other towns and cities had only a hand full of barbers. Danville (2), Augusta (1), Princeton (1), Hopkinsville (1), Cynthiana (1), Henderson (1), Nicholasville (1), Covington (2), Smithland (2), Paducah (1), Russellville (1), Harrodsburg (1), Shelbyville (2), Georgetown (4), Bowling Green (2), and Versailles (3). If I count correctly, that is 102 Kentucky African American barbers.

45 of the barbers were listed as "mulatto," while 57 were described as "black."

20 barbers owned real estate for a total combined wealth of $19,600. The average barber real estate owner thus owned $980. The wealthiest barber was 55 year old Louisvillian David Graves, who owned $4000 in real estate. These figures are almost certainly incomplete, as wealthy Louisville barber Washington Spradling and prosperous Lexington barber Samuel A. Oldham, were both noted as not owning real estate on the census, which is probably wrong. But again, you work with what you have.

As I made my way through the end of the counties alphabetically today, I was surprised to find a "mulatto" barber named L. Talbot, in Shelbyville (above image). He was 46 years old and lived with his 51 year old wife and 7 year old daughter. Talbot owned $300 in real estate. Very neat!

Friday, April 18, 2014

Wise Barber Advertising

Lexington African American barber Robert S. Taylor demonstrated savvy business sense when he advertised in the March 6, 1861, edition of that city's Observer and Reporter newspaper. In that issue, Taylor wisely did not post a sole advertisement asking customers to come to his shop(s); instead he ran two notices that attempted to appeal to customers staying at two different downtown hotels to come to his shop(s) for his services.

Subtly, the advertisements appeared on different pages of that edition. The first ad, which appeared on page two, offered shaving service for customers staying at the Curd House hotel. Although the ad's headline boldly claimed "Curd House Shaving Saloon," the ad notes in finer print that Taylor's shop was "immediately opposite" the Curd House. It also stated that "expert barbers" were on hand to attend to customers' needs. In addition, it claimed that the shop was "open at all hours."

The Curd House was apparently located on West Vine Street between Mill and Upper Streets.

Taylor's ad marketing to the customers staying at the Phoenix Hotel was on page three of the newspaper. The 1859 Lexington business directory lists Taylor's shop as being on the southwest corner of Main Street and Mulberry Street (now Limestone), which corroborates this location. Like the Curd House ad this ad boldly stated "Phoenix Shaving Saloon." In the ad Taylor claimed that he employed "none but the best barbers" and that his shop was "kept in a style to suit the most fastidious taste."

Looking at an 1855 Lexington city map, it appears that Taylor likely operated two different shops at this time. While both shops appear to be within relatively close distance to each other, they don't seem to be at the same exact location.

I have not been able to confirm whether the Phoenix Hotel or the Curd House employed their own in-house barbers at this time (many hotels and inns did in this era), but I would suspect that they did not and Taylor was attempting to capitalize on that fact with these ads. I would be surprised if the proprietors of these hotels would have let someone advertise for their hotels' customers if they had in-house barbers.

Robert S. Taylor must have been somehow been missed by the census taker in 1860, but is noted as a 17 year old mulatto barber in the 1850 census. A Henry Taylor, who was a 19 year old barber, and also described as mulatto, was living in the household of noted Lexington black barber Samuel A. Oldham in 1850. I would not be surprised to find that the Taylor men were brothers or cousins.

Taylor's advertisements show that antebellum black barbers were entrepreneurial in thinking. They clearly understood their amount of business - and thus their income - could be increased by marketing to white customers that read newspapers daily, stayed in nearby hotel establishments, and needed daily grooming services such as shaving.

Wednesday, April 16, 2014

Just Finished Reading - Black Property Owners in the South

Continuing my search for secondary source information on antebellum black barbers, I found Black Property Owners in the South, 1790-1915, by Loren Schweninger. I became acquainted with Schweninger's writings several years ago due to his several collaborations with my favorite historian, John Hope Franklin.

A couple of Schweninger's past books examine two Southern barbers' experiences. In James T. Rapier and Reconstruction, the author provides a biography of this free black barber in northern Alabama, who became a politician during Reconstruction. And, in In Search of the Promised Land: A Slave Family in the Old South, Schweninger and Franklin cover the Thomas family. One member of this fascinating family, James Thomas, who started as an apprentice (and was James Rapier's uncle), owned a barber shop in Nashville, Tennessee.

While Black Property Owners in the South certainly does not solely focus on barbers, it does include some coverage. Schweninger's intriguing statistics and conclusions are similar to those I am finding. On page 124, Schweninger claims of barbers in the upper South, "Some of them owned cigar stores or bathing establishments or ran small shops selling wigs, ties, lotions, and hats. Most of them invested heavily in city real estate. By 1860, their average realty holdings exceeded $6,500, two and a half times the average for their counterparts in the lower [Southern] states."

Later in his discussion about the post Civil War years, Schweninger contends that "The occupational transition from the antebellum to the postbellum periods was symbolized by the decline among prosperous barbers. In 1860, among realty owners in the South with at least $5,000 worth of property, 5 percent were barbers, and among those with at least $20,000, 10 percent practiced the same trade. By 1870, while the proportion with more than $5,000 remained about the same, those with the larger amount dropped from 10 to 5 percent."

Black Property Owners in the South consists of six chapters. The first chapter covers the understanding of property as was brought by slaves to the New World and provides background information on black property owners during the colonial and Early Republic eras. The next two chapters discusses antebellum property ownership among slaves and free people of color respectively. Chapter four looks at extraordinarily wealthy free people of color, particularly in Louisiana and South Carolina. Schweninger contends that a transition occurred that saw the most wealthy black owners shift from the lower South to the upper South after the Civil War. Chapter five looks at postbellum black property owners, and the final chapter examines prosperous African Americans in the postbellum South.

The amount of wealth that some free people of color were able to accumulate was astounding and a true credit to hard work, frugality, and a strong business sense. But despite the amount of wealth free blacks were able to establish and pass on, they well understood - especially those in the antebellum years - that they walked a precarious road among their potentially jealous white neighbors. While some blacks were able to loan and even sue whites to collect debts, those acts were often done with great care as not to offend those with power.

As a supplement to the book's text (and what I considered a true bonus), Schweninger includes a number of primary source correspondence, petitions, and probate court records in the appendices.

Despite the numerous charts and figures, both percentages and dollar amounts, which I sometimes found distracting, Black Property Owners in the South is an important and eye-opening book, which clearly shows that property ownership was achievable even for slaves. And, for free blacks, it was one of the few ways for them to exercise a measure of independence in a world controlled by others. On a scale of 1 to 5, I give it a 4.75.

A couple of Schweninger's past books examine two Southern barbers' experiences. In James T. Rapier and Reconstruction, the author provides a biography of this free black barber in northern Alabama, who became a politician during Reconstruction. And, in In Search of the Promised Land: A Slave Family in the Old South, Schweninger and Franklin cover the Thomas family. One member of this fascinating family, James Thomas, who started as an apprentice (and was James Rapier's uncle), owned a barber shop in Nashville, Tennessee.

While Black Property Owners in the South certainly does not solely focus on barbers, it does include some coverage. Schweninger's intriguing statistics and conclusions are similar to those I am finding. On page 124, Schweninger claims of barbers in the upper South, "Some of them owned cigar stores or bathing establishments or ran small shops selling wigs, ties, lotions, and hats. Most of them invested heavily in city real estate. By 1860, their average realty holdings exceeded $6,500, two and a half times the average for their counterparts in the lower [Southern] states."

Later in his discussion about the post Civil War years, Schweninger contends that "The occupational transition from the antebellum to the postbellum periods was symbolized by the decline among prosperous barbers. In 1860, among realty owners in the South with at least $5,000 worth of property, 5 percent were barbers, and among those with at least $20,000, 10 percent practiced the same trade. By 1870, while the proportion with more than $5,000 remained about the same, those with the larger amount dropped from 10 to 5 percent."

Black Property Owners in the South consists of six chapters. The first chapter covers the understanding of property as was brought by slaves to the New World and provides background information on black property owners during the colonial and Early Republic eras. The next two chapters discusses antebellum property ownership among slaves and free people of color respectively. Chapter four looks at extraordinarily wealthy free people of color, particularly in Louisiana and South Carolina. Schweninger contends that a transition occurred that saw the most wealthy black owners shift from the lower South to the upper South after the Civil War. Chapter five looks at postbellum black property owners, and the final chapter examines prosperous African Americans in the postbellum South.

The amount of wealth that some free people of color were able to accumulate was astounding and a true credit to hard work, frugality, and a strong business sense. But despite the amount of wealth free blacks were able to establish and pass on, they well understood - especially those in the antebellum years - that they walked a precarious road among their potentially jealous white neighbors. While some blacks were able to loan and even sue whites to collect debts, those acts were often done with great care as not to offend those with power.

As a supplement to the book's text (and what I considered a true bonus), Schweninger includes a number of primary source correspondence, petitions, and probate court records in the appendices.

Despite the numerous charts and figures, both percentages and dollar amounts, which I sometimes found distracting, Black Property Owners in the South is an important and eye-opening book, which clearly shows that property ownership was achievable even for slaves. And, for free blacks, it was one of the few ways for them to exercise a measure of independence in a world controlled by others. On a scale of 1 to 5, I give it a 4.75.

Sunday, April 13, 2014

Friday, April 11, 2014

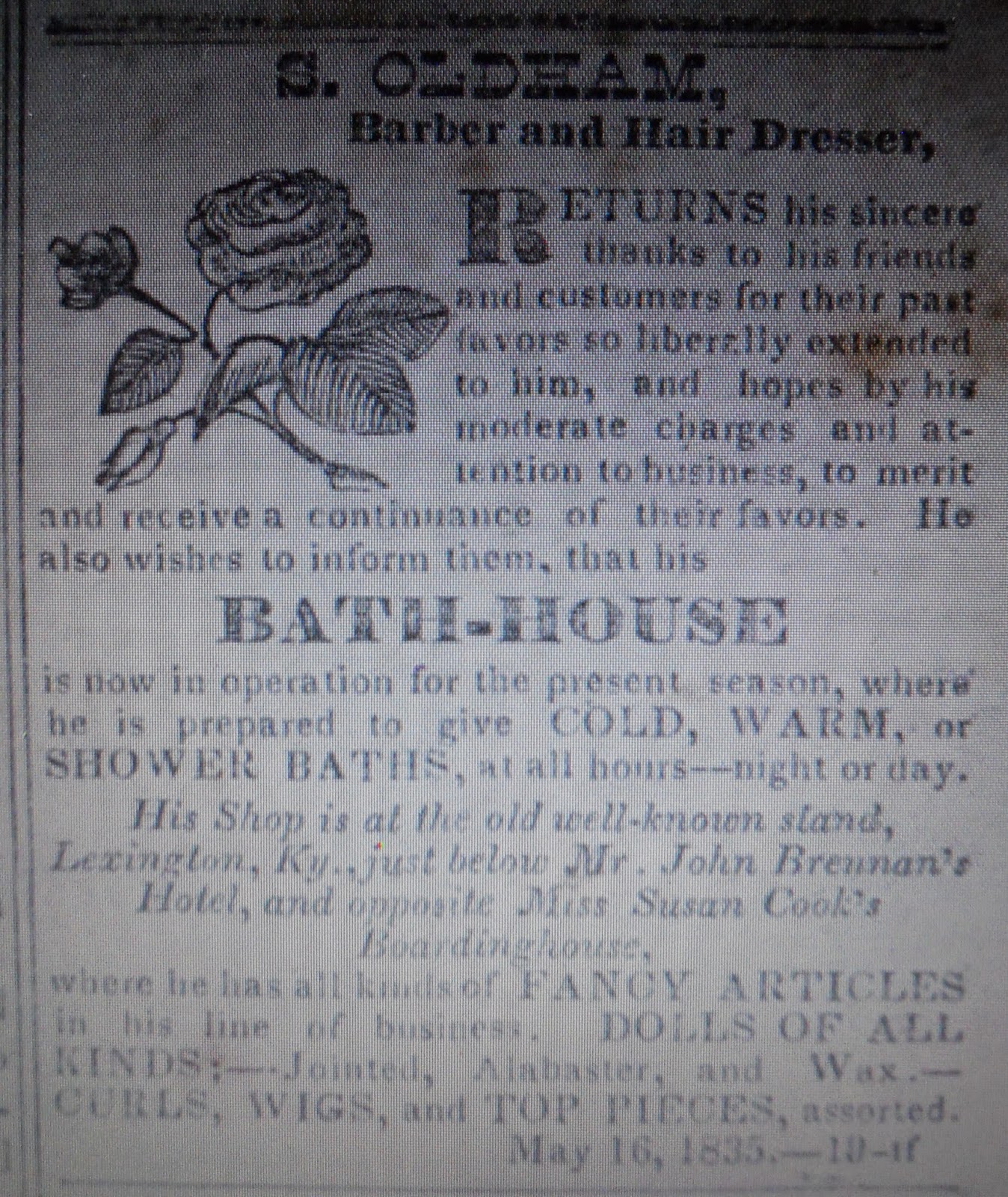

Samuel A. Oldham Advertisements

I have mentioned African American barber Samuel A. Oldham in number of recent posts, but I believe that I have neglected to share any of his advertisements. The earliest of Oldham's ads that I have located (above) so far is one from 1835 that was printed in the Lexington Kentucky Gazette. In it Oldham - as often appears in black barber ads - thanks his past customers for their patronage. Then he promotes his "Bath-House" which offered that service "at all hours--night or day." Oldham next provided clear directions to ensure that potential new customers could find his shop. In addition, and apparently in effort to generate extra revenue, Oldham also advertised that he carried "fancy articles," which meant toiletries, and sold "jointed, alabaster, and wax" dolls, as well as "curls, wigs, and top pieces." I suppose by curls he meant hair extensions, and that his top pieces referred to toupees.

The following year Oldham ran an extended column advertisement that covered much of same material as the previous ad. An interesting point this notice made though was that Oldham had "FOUR HANDS that he can depend upon as Shavers and Hair Cutters."

The above ad, which Oldham ran in 1840, explained to his customers that he had relocated his shop or at least part of his business, to a new address. The ad says his dressing room has moved a block away from his old stand, but the ad does not indicate if the barber shop part had been relocated. However, it seems the bath house moved, too, as well as his "fancy store" that sold toiletries and other assorted goods.

Oldham had at least two sons that followed him into the barber trade. As this ad by his son Nathaniel states, the son had learned barbering from his father in Lexington. The purpose for this ad, which ran in the fall of 1840, was to announce the opening of Nathaniel's shop. Another of Oldham's sons, Samuel C. Oldham seems to have only worked in his father's shop.

Perhaps Nathaniel Oldham's Lexington shop did not prove successful, or maybe his father's business proved too competitive, because he eventually moved to Maysville, Kentucky. Nathaniel is listed there in both the 1850 and 1860 census. Samuel A. Oldham is listed in the 1850 Lexington census as 56 years old and son Samuel C. as 22. Oldham the elder was not listed as having any real estate property in 1850. In 1860, father Oldham was 66 and son Samuel C. was 33. Oldham was listed as having no real estate again in 1860, but was noted as having $1500 in personal property.

The information contained in these advertisements is very valuable in providing a better understanding of their business activities. In addition, it will be interesting to map the location of their shops along with others in the Lexington city directory to see the density of competition for barbering services and to see where barbers chose to locate their businesses.

Tuesday, April 8, 2014

Black Barber John S. Goins "Schooled" at His Shop

In what is probably the most clever and creative antebellum black barber advertisement that I have so far located, Lexington's John Stratford Goins uses comparisons between his craft and that of an academic.

Goins opens the ad by calling his business a "scientific establishment." He then quickly labels himself a "professor of shaving and hair cutting." Goins' scientific establishment is also referred to in the ad as his "college," where he "delivers lectures" in his field of study, i.e. barbering. Goins schooled his customers from "daylight until 10 o'clock at night."

This ad was helpful in that it provided an idea of what barbers charged for their services at that time. For one "lecture on shaving" Goins charged 12 1/2 cents, and 25 cents for a hair cut. In part of his "lecture room" (barber shop), he offered various grooming items, tobacco products, and, for the follicly challenged, he sold wigs and toupees. In addition, behind his "lecture room" Goins, like many other barbers at this time period, offered a bath house, which charged 25 cents per bath. Patrons also had the option of purchasing five bath tickets for one dollar.

Although I was unable to locate census information on Goins, I confirmed his race with the 1838-39 Lexington business directory, which used an "*" to signify that he was African American. In the directory Goins was listed as John S. Goin at 25 East Main Street. His business was labeled as "hairdresser, mediterranean baths." It also appears that Goins lived at his business address. I have not been able to determine yet whether he owned or rented the location.

The year before the "scientific establishment" advertisement appeared, Goins ran an intriguing ad (above) that explained that he had previously operated his business in Frankfort, where he was "long known." The notice also states the he was now taking over the shop previously operated by G. W. Tucker. What is interesting about this is that Tucker had advertised his shop only months earlier in the same newspaper.

Goins' creativity and ingenuity in marketing his business is a pleasant surprise. To me it indicates that he thought "outside of the box" in attempt to bring business into his barber shop and thus increase his earning power.

Monday, April 7, 2014

Just Finished Reading - While in the Hands of the Enemy

If the hundreds of thousands of deaths and terrible wounds caused by the Civil War was not enough to make it "America's greatest tragedy," the physical and mental suffering inflicted on those that became military captives surely confirmed that label.

Ever since the Civil War ended in 1865 North and South have each had their fair share of apologists explaining why almost 56,000 soldiers died in the war's military prisons. Much of that past interpretation was given based on half truths and sustained by biased perspectives. In While in the Hands of the Enemy: Military Prisons of the Civil War, author Charles W. Sanders, Jr., goes a long way toward putting those old interpretations to rest with solid research from a wealth of sources. Sanders proves that there was plenty of blame to go around for all of those thousands of deaths.

I appreciated Sanders opening While in the Hands of the Enemy by providing a brief history of military prisons in America. His examination of prisoner camps in the Revolutionary War, War of 1812, and Mexican-American War gave a better understanding for the situation entering and during the Civil War. Those lessons learned from previous conflicts were seemingly ignored or quickly forgotten though.

In hindsight it seems quite obvious that the conflict between the sections would not only produce death and wounds, but prisoners as well. And while many on both sides thought it would be a short war, little proactive thinking concerning prisoners of war was made. Early battles such as First Manassas and Balls Bluff opened both belligerents' eyes wide to the realities of holding captives.

On the surface and in the present it may not be that difficult to see how deep the animosity ran between the Union and Confederacy (they were after all at war), but the hatred especially comes through in the politics and motivations behind the establishment and then operation of Civil War prisons in both the North and South.

Sanders concedes that "difficulties such as organizational incompetence, inexperience, and chronic shortages of essential resources certainly contributed to the horrors," but he strongly argues that "Union and Confederate leaders . . .knew full well the horrific toll of misery and death their decisions and actions would exact in the camps." Using official reports as well as private correspondence Sanders implicates many big wigs on both sides.

Notorious prison camps such as Andersonville, Elmira, Libby, Camp Douglass, Rock Island, Cahaba, and Danville come in for the greatest amount of coverage. And Sanders implicates men such as Union commissary general of prisoners Lt. Col. William Hoffman and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, and Confederate Secretary of War James Seddon and Commissary General of Subsistence Lucius B. Northrop for decisions that produced willful neglect and were designed to be harmful to those incarcerated.

One of the decisions that Sanders explores is the long held understanding that general prisoner exchanges were stopped by the Union due to the Confederacy's unwillingness to exchange African American soldiers. While the Union brass provided this explanation to the press, Sanders claims that the refusal to continue exchanges had more to do with keeping those captured Southerners off the field of battle and thus increasing the Union's manpower advantage. Simply, the Union could find more men to be soldiers while the Confederacy had a limited amount. In addition, those Union soldiers that "bounty jumped" were less likely to do so knowing that prisoner exchanges were halted.

Sanders ends the book with a very insightful paragraph that succinctly summarized the work. "It is impossible to know the number of deaths that could have been prevented. What is clear, however, is that tens of thousands of captives would not have suffered and died as they did if the men who directed the prison systems of the North and South had cared for them as their own regulations and basic humanity required. Yet this was something that they very deliberately chose not to do. The failure to treat prisoners humanely, young Sabina Dismukes had warned back in 1864, would 'most surely draw down some awful judgement'; and at long last, that verdict must be rendered. For both the Union and the Confederacy, the treatment of prisoners during the American Civil War can only be judged 'a most horrible national sin.'

While in the Hands of the Enemy: Military Prisons of the Civil War is a revisionist work of art. Sanders' arguments are difficult to dismiss with the analysis and evidence he provides. I highly recommend this book about a too often overlooked and marginalized subject. On a scale of 1 to 5, I give it a 4.75.

Ever since the Civil War ended in 1865 North and South have each had their fair share of apologists explaining why almost 56,000 soldiers died in the war's military prisons. Much of that past interpretation was given based on half truths and sustained by biased perspectives. In While in the Hands of the Enemy: Military Prisons of the Civil War, author Charles W. Sanders, Jr., goes a long way toward putting those old interpretations to rest with solid research from a wealth of sources. Sanders proves that there was plenty of blame to go around for all of those thousands of deaths.

I appreciated Sanders opening While in the Hands of the Enemy by providing a brief history of military prisons in America. His examination of prisoner camps in the Revolutionary War, War of 1812, and Mexican-American War gave a better understanding for the situation entering and during the Civil War. Those lessons learned from previous conflicts were seemingly ignored or quickly forgotten though.

In hindsight it seems quite obvious that the conflict between the sections would not only produce death and wounds, but prisoners as well. And while many on both sides thought it would be a short war, little proactive thinking concerning prisoners of war was made. Early battles such as First Manassas and Balls Bluff opened both belligerents' eyes wide to the realities of holding captives.

On the surface and in the present it may not be that difficult to see how deep the animosity ran between the Union and Confederacy (they were after all at war), but the hatred especially comes through in the politics and motivations behind the establishment and then operation of Civil War prisons in both the North and South.

Sanders concedes that "difficulties such as organizational incompetence, inexperience, and chronic shortages of essential resources certainly contributed to the horrors," but he strongly argues that "Union and Confederate leaders . . .knew full well the horrific toll of misery and death their decisions and actions would exact in the camps." Using official reports as well as private correspondence Sanders implicates many big wigs on both sides.

Notorious prison camps such as Andersonville, Elmira, Libby, Camp Douglass, Rock Island, Cahaba, and Danville come in for the greatest amount of coverage. And Sanders implicates men such as Union commissary general of prisoners Lt. Col. William Hoffman and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, and Confederate Secretary of War James Seddon and Commissary General of Subsistence Lucius B. Northrop for decisions that produced willful neglect and were designed to be harmful to those incarcerated.

One of the decisions that Sanders explores is the long held understanding that general prisoner exchanges were stopped by the Union due to the Confederacy's unwillingness to exchange African American soldiers. While the Union brass provided this explanation to the press, Sanders claims that the refusal to continue exchanges had more to do with keeping those captured Southerners off the field of battle and thus increasing the Union's manpower advantage. Simply, the Union could find more men to be soldiers while the Confederacy had a limited amount. In addition, those Union soldiers that "bounty jumped" were less likely to do so knowing that prisoner exchanges were halted.

Sanders ends the book with a very insightful paragraph that succinctly summarized the work. "It is impossible to know the number of deaths that could have been prevented. What is clear, however, is that tens of thousands of captives would not have suffered and died as they did if the men who directed the prison systems of the North and South had cared for them as their own regulations and basic humanity required. Yet this was something that they very deliberately chose not to do. The failure to treat prisoners humanely, young Sabina Dismukes had warned back in 1864, would 'most surely draw down some awful judgement'; and at long last, that verdict must be rendered. For both the Union and the Confederacy, the treatment of prisoners during the American Civil War can only be judged 'a most horrible national sin.'

While in the Hands of the Enemy: Military Prisons of the Civil War is a revisionist work of art. Sanders' arguments are difficult to dismiss with the analysis and evidence he provides. I highly recommend this book about a too often overlooked and marginalized subject. On a scale of 1 to 5, I give it a 4.75.

Saturday, April 5, 2014

A Way Up: Black Barber Apprentices

I felt very fortunate to find the Samuel A. Oldham Papers at the University of Kentucky's special collections. And although the collection only contains 26 items, to have any insight into aspects of the life of a free man of color barber here in Kentucky is quite amazing.

One of the most fascinating items in the collection was an 1851 apprentice agreement (above) between Oldham and a father, who bound out his son, Henry Mitchell, to Oldham for 10 years to learn the barbering trade. Here is a transcription of the document:

I have bound my Son Henry Mitchell to

Samuel Oldham till he is 21 Years old.

He is now 11 Years old on the 1st

day of August 1851. To learn the trade of a Barber which said Oldham is to

teach him & to have him as well Schooled as the nature of the case &

condition of the Free blacks here will admit, and at the end of the time if

Said boy behaves well and Serves faithfully is to give him a new Suit of Sunday

clothes & ten pounds in money witness our hands and seals this 15th

January 1851

Sam'l A. Oldham – Seal

Leaner Lervgin – Seal

His X mark

It seems quite logical why a free parent of color would want their child to apprentice with a barber. It was obvious to all that free black barbers were some of the most financially and socially successful members of the antebellum African American community. Enslaved and free blacks often sought out barbers for personal favors such as loans and serving as power of attorney.

These apprenticeships were likely a win-win situation for all involved; except perhaps those young men who did not particularly want to pursue the profession. The parents were able to place their child with a dependable individual who provided the young man with the skills, knowledge, and experience needed to make their own way in life at a time when professions were limited for African Americans. The barber received a long-term employee and revenue generator, to whom apparently he did not have to pay wages.

In the 1850 and 1860 Kentucky census records I have located a number of young men that were listed as apprentices. Other young barbers were listed in the households of established barbers, but were more than likely apprentices. For example, Samuel A. Oldham's household, in 1850, included his son Samuel C. Oldham, 22 years old, Henry Taylor, 19 years old, and Peter Mallery, 16 years old.

One Lexington barber, G.W. Tucker, even included a "help wanted" addendum to his 1836 newspaper advertisement (above), which sought two young apprentices to work in his shop.

Apprentice opportunities with barbers provided a unique chance for young free men of color - and likely some slaves, too - to take some preliminary steps toward a measure of economic independence.

Tuesday, April 1, 2014

Another History Mystery Solved

Last year I was able to fit a few pieces of information together to help find the identity of a previously unnamed but photographed USCT soldier. A couple of weeks ago, I encountered another conundrum. I shared some Kentucky barber advertisements from the early nineteenth century and pondered on how to determine if they were African American.

I am happy to say that of those three barbers, whose advertisements I showed, I now know the race of at least one. I feel that I have to give partial credit for finding out to plain good fortune, but a measure of persistence helped some, too.

One of those barber advertisements was for a Lexington man named Solomon Bundley. I had been unable to locate Solomon Bundley in the census, but had found an African American Solomon Bunley in Louisville in 1880. I reasoned that the 1880 Solomon - although his last name was spelled slightly different from the advertiser, but phonetically virtually the same - may have been the advertiser's grandson. However, unfortunately, that did not give me much to go on.

Yesterday, I visited the Special Collections at the University of Kentucky to see the Samuel Oldham Papers. Oldham was a free man of color barber in Lexington, who ran a shop for over thirty years. I had hoped that I would find some nuggets of information in his papers that would help me. I'm glad to say and I wasn't disappointed.

Among a number of interesting pieces of information, I came across a power of attorney for one Reuben Bunley given in 1835. In it Bunley explained that his father, Solomon Bunley (ah ha!), had purchased a house and piece of property back in 1808 which had since come under dispute. Reuben Bunley gave Oldham power of attorney to compromise and settle this claim.

Although Reuben Bunley's choice of free man of color Oldham as his power of attorney made me fairly confident in my belief that he, and thus his father, Solomon, were African American, I still wanted more solid information to raise my level of confidence. Having Reuben Bunley's name (which the power of attorney document obviously provided) gave me the missing link of information I needed. Then, searching the 1850 census for Reuben Bundley, I located a free man of color (described as black) of that name in Louisville, who was listed as 58 years old, and, who was - you guessed it - a barber.

Interestingly, Reuben Bunley is listed twice in the 1850 census, both in the 2nd District of Louisville. In the other one he is indicated as Reuben Burnley, a 55 year old black barber. I am not sure why the different ages were recorded by the census taker, but I speculate that one recording was done in the barber shop in which he worked and the other was done at his home, as his family is listed in that second record.

Regardless, my question about the race of the 1813 advertising Solomon Bundley is now answered to my satisfaction. Now, I just need to find out about Thomas Young and Charles Cummens.

I am happy to say that of those three barbers, whose advertisements I showed, I now know the race of at least one. I feel that I have to give partial credit for finding out to plain good fortune, but a measure of persistence helped some, too.

One of those barber advertisements was for a Lexington man named Solomon Bundley. I had been unable to locate Solomon Bundley in the census, but had found an African American Solomon Bunley in Louisville in 1880. I reasoned that the 1880 Solomon - although his last name was spelled slightly different from the advertiser, but phonetically virtually the same - may have been the advertiser's grandson. However, unfortunately, that did not give me much to go on.

Yesterday, I visited the Special Collections at the University of Kentucky to see the Samuel Oldham Papers. Oldham was a free man of color barber in Lexington, who ran a shop for over thirty years. I had hoped that I would find some nuggets of information in his papers that would help me. I'm glad to say and I wasn't disappointed.

Among a number of interesting pieces of information, I came across a power of attorney for one Reuben Bunley given in 1835. In it Bunley explained that his father, Solomon Bunley (ah ha!), had purchased a house and piece of property back in 1808 which had since come under dispute. Reuben Bunley gave Oldham power of attorney to compromise and settle this claim.

Although Reuben Bunley's choice of free man of color Oldham as his power of attorney made me fairly confident in my belief that he, and thus his father, Solomon, were African American, I still wanted more solid information to raise my level of confidence. Having Reuben Bunley's name (which the power of attorney document obviously provided) gave me the missing link of information I needed. Then, searching the 1850 census for Reuben Bundley, I located a free man of color (described as black) of that name in Louisville, who was listed as 58 years old, and, who was - you guessed it - a barber.

Interestingly, Reuben Bunley is listed twice in the 1850 census, both in the 2nd District of Louisville. In the other one he is indicated as Reuben Burnley, a 55 year old black barber. I am not sure why the different ages were recorded by the census taker, but I speculate that one recording was done in the barber shop in which he worked and the other was done at his home, as his family is listed in that second record.

Regardless, my question about the race of the 1813 advertising Solomon Bundley is now answered to my satisfaction. Now, I just need to find out about Thomas Young and Charles Cummens.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)