Tuesday, December 31, 2019

Books I Read in 2019

This is the third year that I've shared the list of books that I read over the last 365 days. My hope in sharing this list is that readers here may see a title that sparks their interest enough to also read it. Like the past two years I've highlighted those titles that I found particularly enlightening or that I especially enjoyed. So . . . here we go!

1. The Blood of Emmett Till by Timothy B. Tyson

2. The War for the Common Soldier: How Men Thought, Fought, and Survived Civil War Armies by Peter S. Carmichael

3. Intensely Human: The Health of the Black Soldier in the American Civil War by Margaret Humphreys

4. Corporal Si Klegg and His Pard by Wilbur F. Hinman

5. Denmark Vesey's Garden: Slavery and Memory in the Cradle of the Confederacy by Ethan J. Kytle and Blaine Roberts

6. Braxton Bragg: The Most Hated Man of the Confederacy by Earl J. Hess

7. Nat Turner and the Rising in Southampton County by David F. Allmendinger

8. Embattled Freedom: Journeys through the Civil War's Slave Refugee Camps by Amy Murrell Taylor

9. Faces of the Civil War Navies by Ronald Coddington

10. DeBow's Review: The Antebellum Vision of a New South by John V. Kvack

11. Nature's Civil War: Common Soldiers and the Environment in 1862 Virginia by Katheryn Shively Meier

12. The Good Lord Bird by James McBride

13. Oberlin: Hotbed of Abolitionism by J. Brent Morris

14. American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia by Edmund S. Morgan

15. God's Almost Chosen Peoples: A Religious History of the American Civil War by George C. Rable

16. Lincoln and the Abolitionists by Stanley Harrold

17. Money Over Mastery, Family Over Freedom: Slavery in the Antebellum Upper South by Calvin Schermerhorn

18. Hard Marching Every Day: The Civil War Letters Private Wilbur Fisk, 1861-1865, ed. by Emil Rosenblatt et al.

19. The Quarter and the Fields: Slave Families in the Non-Cotton South by Damian Alan Pargas

20. Iron Dawn: The Monitor, the Merrimack, and the Civil War Sea Battle that Changed History by Richard Snow

21. Looming Civil War: How 19th Century Americans Imagined the Future by Jason Phillips

22. General Lee's Immortals: The Branch-Lane Brigade by Michael C. Hardy

23. Letters from the Storm: The Intimate Civil War Letters of Lt. J. A. H Foster, ed. by Walter L. Dowell

24. Conquered: Why the Army of Tennessee Failed by Larry J. Daniel

25. Private Confederacies: The Emotional World of Southern Men as Citizens and Soldiers by James J. Broomall

26. Huts and History: The Historical Archaeology of Military Encampment during the Civil War, ed. by David Gerald Orr, et al.

27. The Fight for the Old North State: The Civil War in North Carolina, January-May 1864 by Hampton Newsome

28. Slave Trading in the Old South by Frederic Bancroft

29. Raising the White Flag: How Surrender Defined the American Civil War by David Silkenat

30. Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain and the Petersburg Campaign by Dennis A. Rasbach

31. A Great Sacrifice: Northern Black Soldiers, their Families, and the Experience of Civil War by James G. Menendez

32. Practical Liberators: Union Officers in the Western Theater during the Civil War by Kristopher Teeters

33. The First Republican Army: The Army of Virginia and the Radicalization of the Civil War by John H. Matsui

34. War of Vengeance: Acts of Retaliation against Civil War POWs by Lonnie R. Speer

35. Keep the Days: Reading the Civil War Diaries of Southern Women by Steven M. Stowe

36. War Matters: Material Culture in the Civil War Era, ed by Joan Cashin

37. Broke by the War: Letters of a Slave Trader, ed. by Edmund L. Drago

38. Executing Daniel Bright: Race, Loyalty, and Guerrilla Violence in a Coastal Carolina Community, 1861-1865 by Barton A. Myers

39. Richmond Shall Not Be Given Up: The Seven Days' Battles by Doug Crenshaw

40. In the Cause of Liberty: How the Civil War Redefined American Ideals, ed. by William J. Cooper et al.

41. Voices of the Civil War: The Seven Day by Time Life Editors

42. War Stuff: The Struggle for Human and Environmental Resources in the American Civil War by Joan E. Cashin

43. Spying on the South: An Odyssey across the American Divide by Tony Horwitz

44. Sex and the Civil War: Soldiers, Pornography, an the Making of American Morality by Judith Giesberg

45. Seeds of Empire: Cotton, Slavery, and the Transformation of the Texas Borderlands, 1800-1850 by Andrew J. Torget

46. Virtue of Cain: For Slave to Senator - Biography of Lawrence Cain by Kevin M. Cherry Sr.

47. Andersonville: The Last Depot by William Marvel

48. They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South by Stephanie Jones-Rogers

49. Searching for Black Confederates: The Civil War's Most Persistent Myth by Kevin Levin

50. I Remain Yours: Common Lives in Civil War Letters by Christopher Hager

51. The Tie That Bound Us: The Women of John Brown's Family and the Legacy of Radical Abolitionism by Bonnie Laughlin-Schultz

52. March by Geraldine Brooks

53. Henry Clay: The Man Who Would be President by James C. Klotter

54. Thank God My Regiment an African One: The Civil War Diary of Col. Nathan W. Daniels, ed. by C. P. Weaver

55. Slave Against Slave: Plantation Violence in the Old South by Jeff Forret

56. Upon the Fields of Battle: Essays on the Military History of America's Civil War ed. by Andrew Bledsoe et al.

57. The Won Cause: Black and White Comradeship in the Grand Army of the Republic by Barbara Gannon

58. The Weeping Time: Memory and the Largest Slave Auction in American History by Anne C. Bailey

Well, I came up just two books short of last year's total. I guess I'm just going to have to either read shorter books or at a faster pace, but averaging over a book a week again is pretty good. I hope you see something here you might want to read. Happy New Year!

Monday, December 30, 2019

6th USCI White Officer Casualties at the Battle of New Market Heights

As I reviewed the official Medal of Honor citations for the 14 African American enlisted men and non-commissioned officers who received that distinction at the Battle of New Market Heights, I noticed that several were similarly worded. For example, 1st Sgt. James H. Bronson's of Company D, 5th USCI reads: "Took command of his company, all the officers having been killed or wounded, and gallantly led it." 1st Sgt. Robert Pinn's of Company I, 5th USCI reads, " Took command of his company after all the officers had been killed or wounded and gallantly led it in battle." Sgt. Maj. Milton Holland's of Company C, 5th USCI, "Took command of Company C, after all the officers had been killed or wounded, and gallantly led it." Sgt. Maj. Edward Ratcliff's, Company C, 38th USCI states, "Commanded and gallantly led his company after the commanding officer had been killed; was first enlisted man to enter the enemy's works."

Knowing that each company usually had three white officers (captain, 1st lieutenant, and 2nd lieutenant), and that there were normally ten companies in a regiment, that likely made for an extremely high rate of casualties among the white officers leading the five primary regiments (4th, 5th, 6th, 36th, and 38th USCI) in the attack at New Market Heights on September 29, 1864. Interested in seeing if my hypothesis held true, I first looked into the regiment that provided the easiest accessible information.

The book, Strike the Blow for Freedom: The 6th United States Colored Infantry in the Civil War by James M. Paradis includes an appendix that contains a roster of the officers and men in each company of the regiment. Going through each company and corroborating it with service records on Fold3.com I was able to compile the list below. The casualty results were quite startling.

Field Officers

Company Officers

Company A

Capt. Robert Beath - wounded, left leg amputated

Company B

Capt. Charles V. York - killed

1st Lt. Nathaniel Hubbard - wounded, left thigh and scrotum

2nd Lt. Frederick Meyer - killed

Company C

1st Lt. Enoch Jackman - wounded, left hand

Company D

1st Lt. John Johnson - wounded, arm

Company E

None

Company F

None

Company G

2nd Lt. Eber Pratt - mortally wounded, amputation of right thigh

Company H

Capt. George Sheldon - killed

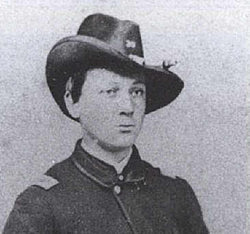

1st Lt. and Adjutant Nathan Edgerton, wounded, hand (pictured above)

1st Lt. LaFayette Landon - mortally wounded, left thigh

Company I

2nd Lt. William McEvoy - mortally wounded, blood poisoning after ex section of left elbow

Company K

None

I will see if I find similar results with the other four primary assault regiments and share them in future posts.

Image, "Three Medals of Honor" by Don Troiani, Historical Artist

Friday, December 27, 2019

Capt. John McMurray Recollects Pvt. Nathaniel Danks

In my December 21 post about Capt. John McMurray's book, Recollections of a Colored Troop, I promised to share some of the stories he told about a few of the men that served with him. Some of these stories are heartbreaking, as the one I shared in the original post about Pvt. Manuel Patterson. Other are significantly more lighthearted. Learning a bit more about these men through their compiled service records, and if possible other sources, gives the modern reader a better understanding of who they were than just a name mentioned in passing. However, often the search leaves us with more questions.

On page 12, McMurray gave us a glimpse of Pvt. Nathaniel Danks' personality. He wrote:

"During the six months we remained in camp at Yorktown we must have marched up and down the Peninsula through Williamsburg at least a half a dozen times. The town was about half a mile long, and seemed to have only one street. Every time we would go through both sides of this Main street were lined with colored people, old and young, male and female, to see the colored soldiers, of whom they were very proud. One day as we were approaching the town going up, I looked ahead, perhaps a quarter mile, and just at the end of the street where we entered the town I saw a negro woman dancing. She continued dancing until we came to where she was, when I observed she was in an ecstasy of excitement. As we marched by her she kept on dancing until she sank to the ground from sheer exhaustion.

Unfortunately, Danks' service records only give a few additional hints of personal information. Danks, born in Philadelphia, and thus apparently a free man of color when he enlisted, was only 25 years old when he joined up at New Brighton, Pennsylvania. New Brighton is on the west side of the state, northwest of Pittsburgh. His service records only give the vague pre-war occupation of "laborer." I was hoping to find him in the 1860 census with fuller information, but nothing came up in my search, nor was he in the 1850 census. Danks is described in his service records as 5 feet, 8 inches tall, with a "dark" complexion and black eyes and hair.

Danks enlisted in Company D of the 6th United States Colored Infantry for three years on July 16, 1863, and formally mustered in on August 10 in Philadelphia, at Camp William Penn. He is shown as present for duty on every company muster roll, until the September and October card, for which he is described as "missing in action taken prisoner or killed Sept. 29, 1864."

McMurray's Recollections (pg. 55) later tells us that Danks was among the killed in the desperate charge at the Battle of New Market Heights. McMurray's Company D went into the fight with 30 men and came out with only three. The 6th USCI as a whole lost almost 60% of its men killed, wounded, or missing.

Rest in peace Pvt. Danks. Thank you for your service to the United States and for sacrificing your life for the Declaration of Independence's ideal that "all men are created equal."

Thursday, December 26, 2019

Capt. Charles V. York, 6th USCI

Photographic images of Civil War

soldiers are not difficult to find. Period photographers’ ability to produce

calling card sized images—carte de visites, or CDVs—made giving out one’s image

the popular thing to do. In the William Gladstone Collection, which Pamplin

Historical Park and the National Museum of the Civil War Soldier owns and cares

for, there are hundreds of CDVs, the vast majority of which focus on African

American related subjects.

One image, seemingly like so many others

upon first glance, is that of Captain Charles V. York of the 6th

United States Colored Infantry (USCI). But, like all photographs, there is a story

behind the person pictured on it.

Charles York was 25 years old when he

enrolled in the 6th USCI on August 8, 1863 in Washington DC. York

had prior experience as a sergeant in the 10th New York Heavy

Artillery. Like other white officers commanding black troops, he was required

to pass an examination. The intent of these examinations was to determine the

fitness of the candidate to lead African American soldiers, and to weed out

those just looking for a quick promotion. York passed and received a commission

as 1st lieutenant.

York’s first responsibility with the 6th

USCI was as adjutant. His duties included writing orders and keeping the

regiment’s records. However, on March 24, 1864, York received a promotion to

captain, commanding Company B. He participated in the fighting on June 15, 1864,

which opened Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s first offensive of the Petersburg

Campaign. The 6th experienced its first true combat at Baylor’s Farm

that morning and then with the attacks by Gen. Edward Hinks’s Division on the eastern

section of the Confederate Dimmock Line later that day. York appears to have

survived unscathed.

However, illness struck York in August.

His service records specify his ailment. Dr. Ely McClellan, York’s examining

surgeon at Fort Monroe, Virginia, stated on August 20, 1864, that his patient

“is now suffering from Diarrhea and extreme debility the result of exposure and

fatigue.” The physician explained that York “has been incapacitated for duty

for the past ten (10) days. He absolutely requires a few days rest and medical

treatment to fit him for active service.”

Apparently, York’s superiors felt he

overstayed his hospital visit, or at least did not follow the proper protocol

to extend this recuperative stay. Because on September 23, Col. John W. Ames,

commander of the 6th USCI, requested the appointment of a commission

to investigate York’s absence without leave. Proceeding up the chain of

command, brigade commander, Col. Samuel A. Duncan, approved the request stating,

“Capt. York, tho’ now returned, has offered no explanation for his continued

absence.” Finally, XVIII Corps, 3rd Division commander, Brig. Gen.

Charles J. Paine, ordered on September 27 that “let charges be sent forward

without delay as a Ct. Ml. [court martial] is now in session.”

That courts martial would never try

Capt. York. Instead, he received a mortal wound in the savage fighting two days

later, September 29, 1864, at the Battle of New Market Heights, just outside of

Richmond. During the battle, Capt. John McMurray of Co. D, saw York lying

beside a path through the abatis, suffering from a terrible wound. McMurray

made a mental note of York’s location and continued in the advance. Returning

to the spot after the fight, McMurray found York stripped of all his

possessions, including his uniform. York had scribbled his name, rank, and

regiment on a slip of paper and pinned it to the chest of his undershirt where

it remained when McMurray found him.

The next time you view a photograph of a

Civil War soldier, stop and remember, they all have a story. You can learn some

of those stories by visiting Pamplin Historical Park and the National Museum of

the Civil War Soldier.

Disclaimer: I originally wrote this article for the "Behind the Scenes at Pamplin" section published regularly in the Petersburg Progress Index newspaper.

Tuesday, December 24, 2019

A Soldier's Christmas

For Civil War soldiers in the field,

Christmas could be a joyous occasion, or just another day of marching depending

on their orders. For Lt. Charles Morfoot and his comrades in the 101st

Ohio Volunteer Infantry on December 25, 1864, it was the later. Writing to his

wife, Elizabeth, the day after Christmas, from “7 miles Southwest of Columbia,

Tenn,” Morfoot and the Union army was in hot pursuit of Gen. John Bell Hood’s

Army of Tennessee after a decisive Federal victory just outside of Nashville,

Tennessee, on December 15-16.

After describing leaving Nashville and continuously

pushing the Confederates, Morfoot wrote, “Yesterday, Christmas was a hard day

on us. It was wet and muddy.” He stated that “it was very cold,” and that the

ground was frozen, with “snow storms” thrown in for good measure. The veteran

soldier Morfoot understood it did little good to complain, but he also seemed

to want those at home to know his trials. “It is not pleasant lying out on the

cold, frozen ground, but it is done, and no grumbling, for we are doing good

work now.”

Morfoot explained to Elizabeth about the

damages the Union army had inflicted on the Confederate Army of Tennessee. “We have killed

or captured over one-third of Hood’s army and taken about all of his

artillery,” he wrote. The Federal pursuit had caused the Southerners to destroy

many of their supply wagons to prevent capture and to speed their escape. Morfoot

hoped he could go into winter quarters soon. He stated, “I will be glad to get

the rest, we have been going so long.”

Soon though, Morfoot turned his thoughts

back to Elizabeth. “Well, I hope you had a Merry Christmas and plenty to eat.”

However, he again seemed to seek acknowledgement of his sacrifices for the good

of the country. “I can’t say so much for myself. I had enough for breakfast

yesterday. . . . I had coffee alone this morning. I had coffee and fresh beef

since, nothing else. We are lying still today, waiting for the supply train to come

up. It will be here tonight. Then we are to get 3 day’s rations to last 5.”

Morfoot’s exasperation with army life, and probably being away from loved ones

at this time of year, caused him to unveil his frustrations. “Curse them – let

them rip; only 8 months more [to serve].”

Morfoot ended his letter by describing

the horrific sights of the Franklin, Tennessee battlefield as they passed

through that town in pursuit of Hood’s army. He also mentioned seeing a couple of friends

now in the army that he had known back home. He closed, “I say farewell until

we meet again, and remain yours.”

Lt. Charles Morefoot would not need to

wait eight months to end his army career. He mustered out at Camp Harker,

Tennessee, on June 12, 1865, and returned home. Morfoot’s holiday missive reminds

us to be thankful for those who presently serve to defend our freedoms and to

count our blessings, particularly at this time of year.

The Morfoot letter is among those in the

Wiley Sword Collection, held and preserved by Pamplin Historical Park and the

National Museum of the Civil War Soldier.

Disclaimer: I originally wrote this article for the "Behind the Scenes at Pamplin" section published regularly in the Petersburg Progress Index newspaper.

Monday, December 23, 2019

A Soldier's Load

At Pamplin Historical Park and the National Museum of the Civil War

Soldier’s permanent exhibit, “Duty Called Me Here: The Common Soldier’s

Experience in the American Civil War,” two interactive kiosks allow guests to

choose what they wish to carry if they were a soldier and then weighs their

load. This exercise suggests that veteran soldiers carried the bare minimum

when possible to reduce their level of physical exertion.

In addition to a soldier’s rifle-musket, which weighed about 10 pounds,

their leather cartridge box full of 40 rounds of ammunition and waist belt with

bayonet and scabbard, all of which made for about another 10 pounds, soldiers also

had to tote a canteen and haversack. Depending on their level of contents,

these items could add an additional ten or more pounds. On top of the items

hanging by various straps, the soldier’s woolen uniform jacket, trousers, hat,

and shoes added about another 10 pounds or so of burden.

Soldiers often commented on their loads in their letters home. For

example, the Charles Hunter Collection at Pamplin Historical Park contains a

letter from this soldier to his sister back in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania explaining his

necessary food and equipment for an upcoming campaign.

Written on April 20, 1863, from Fletcher’s Chapel (near

Fredericksburg), Virginia, Hunter opens with a traditional soldier’s greeting,

“I received your kind letter last night and was glad to hear that you were all

well as this [letter] leaves me in good health at present.” Hunter explained,

“We are expecting to march every day as we are under orders.” Hunter served in

the 88th Pennsylvania Infantry, part of the I Corps of the Army of

the Potomac at this point in the war. Now commanded by Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker,

the Army of the Potomac was under pressure from Washington D.C. to reverse

previous setbacks. Preparing for extended campaigning often meant extra loads

for infantrymen.

“We have 8 days of rations to carry with us when we do go and every man

has to carry that much,” Hunter wrote. To give his sister Jane an idea of what

that meant, he explained further. “So you can form some idea what a load, we

will have 80 crackers [hardtack] that is 10 a day.” For additional rations they

received “a spoonfull & a half of sugar and 2 spoonfulls of coffee a day

that will be 12 [spoonfuls] of sugar & 16 of coffee for the eight days.”

Army rations also included meat. Hunter stated they received “3 lbs. of fat

pork for 3 days.” To help supplement possible meat deficiencies, “the cattle

will follow us up for the other 5 days for our fresh beef.”

On top of carrying his soldier gear and rations, Hunter explained other

items he had to lug. “So what with 8 day rations and one [extra] shirt &

drawers & woolen blanket & rubber blanket & half of a tent [shelter

half] you can think it won’t be an easy load, and it won’t be much wonder if a

great many men will have to drop out on the way.”

As Civil War soldiers gained experience they usually either acclimated

to their burdens or found practical ways to minimize their possessions.

Regardless of how soldiers eventually managed their loads, their levels of

physical endurance are inspiring.

Disclaimer: I originally wrote this article for the "Behind the Scenes at Pamplin" section published regularly in the Petersburg Progress Index newspaper.

Image of Pvt. Albert H. Davis, Co. E, 9th New Hampshire Infantry, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Sunday, December 22, 2019

Lt. Freeman Bowley's Capture at the Crater

In my search for information on prisoners of war captured during the Petersburg Campaign, I've been hoping to come across some accounts that give an idea of what soldiers experienced as they were being conveyed to the rear. One that I located comes from Lt. Freeman Bowley of Company H, 30th United States Colored Infanry.

Bowley's Civil War field experience was a short but desperate affair. Bowley mustered into the 30th USCI on May 4, 1864. He was just 18 years old when he participated in the Battle of the Crater. During the savage battle Bowley was captured in the crater caused by the mine explosion with some of his men. He remembered: "A Confederate sergeant advised me to 'take off them thar' quipments,' and as his musket was at full cock and his hand very nervous, the advice was taken. Then he kindly told me to go to the right, where I would find a covered way, and not go across the open field, 'as you'uns people is shelling right smart.' I was among the last to leave. All the colored prisoners who could walk were sent to the rear. None of the severely wounded black soldiers were ever brought back.

I started for the rear, toward the covered way, so kindly designated by the Confederate sergeant, but found it full of troops - South Carolinians. A lieutenant gabbed my haversack, pulling it off, and hit me with the flat of his saber, saying to me 'Git across that-a-way, you damned Yank,' sending myself and others over the field where our men were shelling. Before I got across, a black soldier was killed within four feet of me by one of our own shells. A little further back, out of the range of our fire, two Johnnies went for my watch, and got it; another wanted by cap, but, after a wrangle, I retained it. A third line of battle was lying in the ditch across the ravine, and General Mahone, riding a little sorrel horse, was close behind them. A mile in the rear, I found a lot of our comrades, who had been captured in the morning; among them Lieutenants Sanders and Smith, of my own regiment. We numbered 79 officers and 101 enlisted men. When they took the name of the officers many officers of colored regiments gave the name of a white regiment, but Lieutenant Sanders and myself decided to face the music and gave our regiment '30th United States Colored Infantry,' and saw the words 'Negro Officer' written opposite our names."

In a future post I will share Bowley's experience as he and his fellow black and white Union prisoners were marched through the streets of Petersburg while the city's citizens shouted their contempt. Bowley fortunately survived his prisoner of war ordeal and mustered out of the service in December of 1865. He moved to California where he died in 1903 at age 56.

Bowley's Civil War field experience was a short but desperate affair. Bowley mustered into the 30th USCI on May 4, 1864. He was just 18 years old when he participated in the Battle of the Crater. During the savage battle Bowley was captured in the crater caused by the mine explosion with some of his men. He remembered: "A Confederate sergeant advised me to 'take off them thar' quipments,' and as his musket was at full cock and his hand very nervous, the advice was taken. Then he kindly told me to go to the right, where I would find a covered way, and not go across the open field, 'as you'uns people is shelling right smart.' I was among the last to leave. All the colored prisoners who could walk were sent to the rear. None of the severely wounded black soldiers were ever brought back.

I started for the rear, toward the covered way, so kindly designated by the Confederate sergeant, but found it full of troops - South Carolinians. A lieutenant gabbed my haversack, pulling it off, and hit me with the flat of his saber, saying to me 'Git across that-a-way, you damned Yank,' sending myself and others over the field where our men were shelling. Before I got across, a black soldier was killed within four feet of me by one of our own shells. A little further back, out of the range of our fire, two Johnnies went for my watch, and got it; another wanted by cap, but, after a wrangle, I retained it. A third line of battle was lying in the ditch across the ravine, and General Mahone, riding a little sorrel horse, was close behind them. A mile in the rear, I found a lot of our comrades, who had been captured in the morning; among them Lieutenants Sanders and Smith, of my own regiment. We numbered 79 officers and 101 enlisted men. When they took the name of the officers many officers of colored regiments gave the name of a white regiment, but Lieutenant Sanders and myself decided to face the music and gave our regiment '30th United States Colored Infantry,' and saw the words 'Negro Officer' written opposite our names."

In a future post I will share Bowley's experience as he and his fellow black and white Union prisoners were marched through the streets of Petersburg while the city's citizens shouted their contempt. Bowley fortunately survived his prisoner of war ordeal and mustered out of the service in December of 1865. He moved to California where he died in 1903 at age 56.

Saturday, December 21, 2019

Recollections of a Colored Troop by Capt. John McMurray, Co. D, 6th USCI

A little known source from a white officer in the United States Colored Troops is the memoir written by Capt. (Brevet Maj.) John McMurray, Company D, 6th United States Colored Infantry. I just recently found out that Recollections of a Colored Troop is available in digital scan version through the Library of Congress.

A teacher before the war, McMurray originally served in the 135th Pennsylvania Infantry, a nine-month regiment, attaining a lieutenancy. However, when the 135th mustered out in May 1863, McMurray was in a sort of limbo until he learned about the formation of the United States Colored Troops and applied for a commission. After clearing the USCT screening process, McMurray received a captaincy with Company D, 6th United States Colored Infantry, which was organizing and training at Camp William Penn, near Philadelphia.

In Recollections of a Colored Troop, McMurray shares his memories of his times in camp, on the march, and on the battlefield. It is interesting to read his mentions of specific enlisted men, and then checking their service records. For example, in chapter 14, McMurray mentions William Law, a seemingly model soldier, who at 21 years old and standing at 6 foot 1 inches, served as a color bearer. Yet, in the regiment's first true action at Baylor's Farm, June 15, 1864, just outside Petersburg's defenses, Law was not up to the demanding task. After being turned around by McMurray twice to face the enemy, Law threw down the colors and crawled to the rear. Law's service records show that he became sick on June 21. He remained absent sick over the next several months and died of chronic dysentery on October 27, 1864. One has to wonder if his illness had affected his courage a few days earlier.

Another man, Pvt. Emanuel (aka Manual) Patterson, met his fate at the Battle of New Market Heights on September 29, 1864. Patterson had complained to McMurray about feeling unwell before being transported to Deep Bottom, but the surgeon dismissed Patterson's complaint. Still feeling unwell the morning of the 29, McMurray took Patterson to see the surgeon again. Once more the doctor said Patterson was fine. Patterson assumed his position in line and participated in the attack. As McMurray remembered, "As I was pushing on through the slashing I met him suddenly, presenting one of the most terrible spectacles I ever beheld. He was shot in the abdomen, so that all of his bowels gushed out, forming a mass larger than my hat, seemingly, which he was holding up with his clasped hands to keep them from falling at his feet. Then, and a hundred times since, I wished I had taken the responsibility of saying to him he could remain at the rear."

|

| Pvt. Patterson's death record |

McMurray's memories of the Battle of New Market Heights vividly describe the horrors of that fight. His Company D was left with only three men not killed, wounded or missing when all was said and done on September 29.

McMurray's recollections also include thoughts on the Wilmington Campaign, hearing of the Confederate surrenders, eventual mustering out in the fall of 1865, and traveling back home to Brookville, Pennsylvania.

Recollections of a Colored Troop is an underappreciated but certainly valuable source.

Thursday, December 19, 2019

Just Finished Reading - Slave Against Slave

The historiography of the institution of slavery in the United States is one that has many twists and turns. Since slavery's abolition with the 13th Amendment in late 1865 to the present, scholars have examined and interpreted the "peculiar institution" from different angles and have come to many different conclusions. Along the way, scholars chose different facets of slavery for further investigation. However, few plumbed the depths of intraracial violence.

With Slave Against Slave: Plantation Violence in the Old South, historian Jeff Forret fills a once gaping void. One popular interpretation in the historiography is that slave communities, although plagued by violence or threats from owners, overseers, and other whites, were otherwise "sites of unwavering harmony and solidarity." Forret's research though finds that acts of harm were not uncommon among enslaved populations. Using extant plantation and court records, as well as church discipline records, and slave narratives Forret crafts a comprehensive work spanning almost 400 pages of text.

Broken into eight engaging though at times emotionally draining chapters, Slave Against Slave examines specific topics of intraracial violence including among others: "Violence at Work and Play," "Violence in the Slave Economy," "Violence in the Creation, Maintenance, and Destruction of Slave Unions," "Honor, Violence, and Enslaved Masculinity," and "Honor, Violence, and Enslaved Femininity."

In an environment of constant oppression and control of one's will it is not surprising that during work situations, and often in times of competitive recreation, enslaved people lost their self control and lashed out at those who annoyed or posed threats. As Forret explains, while some of the most extreme cases of intraracial violence led to court cases, and thus left us documents to examine and form a historical record, masters often handled less severe cases internally with their own forms of discipline. So determining quantitatively the frequency of slave on slave violence is difficult. However, enough evidence survives to show that harmful acts within the slave community did happen.

With some owners renting out their slaves and allowing them to keep some of their earnings, or with slaves finding opportunities for a measure of financial gain with overwork and thus acquiring money and some types of property, situations developed where jealousies and class differentials emerged that caused rivalries. These sometimes turned violent within the confines of enslavement. Forced unions, and sometimes even loving relationships, ended in violent confrontations when nerves were frayed, frustrations spurred, and choices for individual time were limited. Likewise threats to a loved one, or their relationship, sometimes brought out defensive violence in the slave quarters.

The chapter that I found most thought provoking were the last two on enslaved male and female expressions of honor. Honor, one thought to be the sole territory of white Southern males, gets challenged by Forret with solid evidence and enlightening interpretation. On page 293, he writes, "For some enslaved men, violence in the quarters afforded one means to construct a masculine identity within the context of a white society that routinely denied their manhood. However detrimental or disruptive conflicts were to the harmony and solidarity of the slave community, physical aggression was often crucial to the definition of enslaved masculinity." For example, on page 302, Forret further clarifies: "Most slights coming from the mouths of whites went ignored altogether, although occasionally a slave struck out violently at a verbally abusive master or overseer or took revenge opportunistically through 'Snopesian crimes' such as theft or arson. By contrast, when slaves spit verbal venom upon another, it stung. Just as southern white men bristled at the insults of other white men, slave could not dismiss the insults of their peers. Slaves inhabited the same social plane, and if one's equal voiced insult, it mattered: one slave was attempting to establish superiority or dominance over another and deny the second slave's expectation of treatment as an equal." Enslaved women, too, often had motives for violent acts. Forret found that, "Against other female slaves they employed violence to preserve relationships and families and to maintain their good word and reputation inside the slave community" (p. 382).

We sometimes forget that people of the past were human individuals. They had hopes, dreams, likes and dislikes, just as we do. They experienced frustrations and threats, and some responded with violence, whether justified or not, just as some people do today. To study this facet of enslaved life (within proper context and with historical documentation) only enhances the humanness of those of the past. I highly recommend this book.

With Slave Against Slave: Plantation Violence in the Old South, historian Jeff Forret fills a once gaping void. One popular interpretation in the historiography is that slave communities, although plagued by violence or threats from owners, overseers, and other whites, were otherwise "sites of unwavering harmony and solidarity." Forret's research though finds that acts of harm were not uncommon among enslaved populations. Using extant plantation and court records, as well as church discipline records, and slave narratives Forret crafts a comprehensive work spanning almost 400 pages of text.

Broken into eight engaging though at times emotionally draining chapters, Slave Against Slave examines specific topics of intraracial violence including among others: "Violence at Work and Play," "Violence in the Slave Economy," "Violence in the Creation, Maintenance, and Destruction of Slave Unions," "Honor, Violence, and Enslaved Masculinity," and "Honor, Violence, and Enslaved Femininity."

In an environment of constant oppression and control of one's will it is not surprising that during work situations, and often in times of competitive recreation, enslaved people lost their self control and lashed out at those who annoyed or posed threats. As Forret explains, while some of the most extreme cases of intraracial violence led to court cases, and thus left us documents to examine and form a historical record, masters often handled less severe cases internally with their own forms of discipline. So determining quantitatively the frequency of slave on slave violence is difficult. However, enough evidence survives to show that harmful acts within the slave community did happen.

With some owners renting out their slaves and allowing them to keep some of their earnings, or with slaves finding opportunities for a measure of financial gain with overwork and thus acquiring money and some types of property, situations developed where jealousies and class differentials emerged that caused rivalries. These sometimes turned violent within the confines of enslavement. Forced unions, and sometimes even loving relationships, ended in violent confrontations when nerves were frayed, frustrations spurred, and choices for individual time were limited. Likewise threats to a loved one, or their relationship, sometimes brought out defensive violence in the slave quarters.

The chapter that I found most thought provoking were the last two on enslaved male and female expressions of honor. Honor, one thought to be the sole territory of white Southern males, gets challenged by Forret with solid evidence and enlightening interpretation. On page 293, he writes, "For some enslaved men, violence in the quarters afforded one means to construct a masculine identity within the context of a white society that routinely denied their manhood. However detrimental or disruptive conflicts were to the harmony and solidarity of the slave community, physical aggression was often crucial to the definition of enslaved masculinity." For example, on page 302, Forret further clarifies: "Most slights coming from the mouths of whites went ignored altogether, although occasionally a slave struck out violently at a verbally abusive master or overseer or took revenge opportunistically through 'Snopesian crimes' such as theft or arson. By contrast, when slaves spit verbal venom upon another, it stung. Just as southern white men bristled at the insults of other white men, slave could not dismiss the insults of their peers. Slaves inhabited the same social plane, and if one's equal voiced insult, it mattered: one slave was attempting to establish superiority or dominance over another and deny the second slave's expectation of treatment as an equal." Enslaved women, too, often had motives for violent acts. Forret found that, "Against other female slaves they employed violence to preserve relationships and families and to maintain their good word and reputation inside the slave community" (p. 382).

We sometimes forget that people of the past were human individuals. They had hopes, dreams, likes and dislikes, just as we do. They experienced frustrations and threats, and some responded with violence, whether justified or not, just as some people do today. To study this facet of enslaved life (within proper context and with historical documentation) only enhances the humanness of those of the past. I highly recommend this book.

Wednesday, December 18, 2019

"The Colored Pickets of the 9th Corps"

While searching through some Northern newspapers to find how they covered the Battle of New Market Heights (of which I found very little mention), I came across the short notice above. It was printed in the October 1, 1864 edition of Cleveland Morning Leader, a Republican newspaper.

United States Colored Troops (USCT) in the trenches ringing Petersburg by this point in the campaign experienced almost constant harassment from their Confederate adversaries, Often located within hailing distance of each other, contemptuous exclamations were offer and returned in full and shots from both rifles and artillery flew hot and fast.

Gen. Edward Ferrro's USCT Division of the IX Corps, positioned southeast of Petersburg, had full knowledge of their enemies. They had battled them tooth and nail at the Battle of the Crater about two months before this article was printed. And in the time in between, as mentioned above, heavy firing between the pickets and men in the earthwork trenches kept their heads down but their tempers up.

This particular mention though claims that things had cooled somewhat between the foes. Its writer contends that now Confederates did not fire on black soldiers "any more promptly than white [Union] soldiers". It even says that "Deserters are also willing to accept food from colored soldiers, and will sit and chat with them."

Confederate deserters were a different kind of prisoner, and one I have honestly not given much consideration to in my research. It stands to reason that those soldiers who willingly gave themselves up rather than being captured in the heat, passion, and confusion of battle would receive more kind treatment than otherwise. And it is not had to believe that those who were hungry at the time of their capture would accept food, wherever it came from, perceived inferiors or not. I will be keeping my eyes open for future mentions by soldiers on both sides who found themselves in these situations.

Tuesday, December 17, 2019

Anthony M. Keiley's Petersburg Capture

Early in my search for prisoner of war accounts during the Petersburg Campaign, I came across that of Anthony M. Keiley. Although not captured during what is traditionally known as the Petersburg Campaign (June 15, 1864 - April 2, 1865), Keiley's story is one of the most complete that I've found. Keiley became a prisoner on June 9, 1864, when Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler made an attempt on the Cockade City with a force of Army of the James infantry and cavalry that was eventually thwarted.

Keiley was among the scratch force, the so-called "old men and young boys" defenders called out to guard Petersburg. The title old men and young boys seems a bit of a stretch as most more closely fit the description of middle aged men and middle to late teens. Regardless, I was curious to see why Keiley was not serving in the regular army, as he was only about 30 years old at the time. I conducted an online search and found that he had previously served in the 12th Virginia Infantry, a regiment largely raised in Petersburg.

A quick review of Keiley's extensive service records tells his military story. Involved with a Petersburg newspaper before the war, Keiley enlisted as a sergeant in Company E of the 12th Virginia, just two days after Virginia seceded from the Union. In the fall of 1861, Keiley received a promotion to 2nd lieutenant. The 12th Virginia first served at Norfolk and then were transferred to Drewry's Bluff and then to Richmond where the Seven Days' Battles were raging.

On July 1, 1862, the last day of the Seven Days' fighting, the 12th Virginia got into the fight at Malvern Hill as part of William Mahone's Brigade. In the fight, now 1st Lt. Keiley received a wound to the instep of his foot. His service records also state that he suffered from an illness that kept him absent on sick leave through the fall of 1862. However, by January and February 1863, Keiley was back with his comrades in the 12th Virginia. One letter in his records says that although he was not healed he joined his regiment at Fredericksburg. Other records, early in 1863, show that he attempted to get a detached position as a courier apparently without success. His July and August 1863 return shows him again on leave. Another source said that he was at Gettysburg, but Mahone's Brigade was largely not engaged in that fight. Keiley remained on leave but he was elected to the General Assembly at which time he requested to resign and it was accepted by December 1863.

By the summer of 1864, Keiley was back in Petersburg, again working in the newspaper business. Called out to defend the city and captured during the June 9 attack on the city he was sent to Butler's headquarters at City Point or Bermuda Hundred.

Keily's book, published in 1866 as, In Vinculis, Or Prisoner of War Being the Experience of a Rebel in the Federal Pens, among other things, gives his racist impression of the African American guards at Butler's headquarters.

Keiley wrote in his chapter 4, "Beast Butler:" that "On approaching Butler's quarters, which were quite handsomely located, out of reach of all intrusion, the first thing that attracted attention was the presence and prominence of the negro. So far we had only seen one or two of the negro soldiers on duty at the pontoon bridge, and the night being as dark as themselves, we could with difficulty distinguish them--but there Abyssinia ruled the roast [roost?]. It was 'nigger' everywhere; and although the white soldiers were obviously annoyed at the companionship, the terror of Butler's rule crushed all resistance even of opinion, and all the colored brethren knew, and presumed on, their secured position and importance."

I'll be sharing other selections from In Vinculis in the near future as I work my way though its pages.

Postwar image of A.M. Keiley courtesy of the Virginia Museum of History and Culture.

Monday, December 16, 2019

Recent Acqusitions to My Library

In addition to those books that I received for my birthday back in November, I also received a generous gift card, which allowed me to haul in some more titles from my wish list.

I sometimes give custom tours of Civil War Era Richmond, Virginia sites. There are several good books out there about the Confederate capital city, but most have to do with the political and military aspects of the city. A new book, Rebel Richmond: Life and Death in the Confederate Capital by Stephen V. Ash, looks to open up the narrative and include more about the common people's war experience. I've enjoyed reading many of Ash's books and certainly look forward to diving into this one.

The largest slave auction in antebellum America occurred in early March 1859 in Savannah, Georgia. To help pay off enormous debts, Pierce M. Bulter sold over 430 men, women, and children to buyers who took their human property to diverse locations across the slave states. Their sale netted Butler over $300,000. In The Weeping Time: Memory and the Largest Slave Auction in American History, author Anne C. Bailey recounts not only the lead up to the auction and its events, but also how this episode in United States history was and is remembered by those it impacted most.

A Broken Regiment: The 16th Connecticut's Civil War by Lesley J. Gordon is a book that I've wished to add to my collection for quite some time. This work covers the unfortunate regiment's Civil War experience, from being raw troops thrown into the grinder at Antietam, to surrendering while serving in North Carolina in 1864, and serving significant time in Confederate prisoner of war camps. But it is also the story of how the regiment came to remember their hard luck service and reshape it to better fit the narrative of Union victory.

James Martin's The Children's Civil War had a significant impact on my understanding of the conflict and how it shaped the lives of Northern and Southern children who experienced it. However, in Topsy-Turvy: How the Civil War Turned the World Upside Down for Southern Children, author Anya Jabour seeks greater specificity in solely examining black and white Southern children. Living where most of the fighting occurred and among a population of people--whether black or white--who "lived" the war most directly, should highlight some interesting stories and draw some intriguing conclusions.

Recent scholarship on slavery has focused heavily on capitalism and the "peculiar institution." Several trailblazing books provide a significant amount of evidence that plantation owners largely viewed their operation as a business and sought to wring as much labor out their enslaved property as possible. Accounting for Slavery: Master and Management by Caitlin Rosenthal continues discussions in this vein. Looking at plantations and their well-kept records in the West Indies and the slaves states of the U.S., she found intricate and innovative business practices being incorporated to help increase planters' profit margins, most often at the expense of those doing the work.

Feed you mind!

Sunday, December 15, 2019

Captured Flag + Captured Flag Bearer = Medal of Honor for Pvt. Frederick C. Anderson, 18th Mass. Inf.

Most Civil War enthusiasts know the important part flags played on that conflict's battlefields. And, a review of citations for Civil War Medal of Honor recipients only confirms the significance of battle standards, both as a symbol and as a practical marker.

The above flag is currently on display at Pamplin Historical Park's National Museum of the Civil War Soldier near Petersburg, Virginia. Its label states that it belonged to the 27th South Carolina Infantry and that it was captured at the Battle of Weldon Railroad, which occurred just south of Petersburg, August 18-21, 1864. What is not mentioned is "the rest of the story," as the late great radio personality Paul Harvey used to say.

This fight, also known as the Battle of Globe Tavern and part of Gen. Ulysses S. Grant's Fourth Offensive at Petersburg, began with a strong move in force by the Army of the Potomac's V Corps, led by Maj. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren. The goal was to capture and hold the Weldon Railroad (aka Petersburg Railroad) which ran south out of the Cockade City into North Carolina and linked with other rail lines to Wilmington on the coast.

The initial movement met with little resistance as the V Corps tore up sections of track near Globe Tavern on August 18. However, as was the case in most of Grant's Petersburg Offensives, it was finally met with a furious Confederate counterattack that resulted in hundreds of captured Union soldiers. Warren then counterattacked the Southerners, regaining control of the railroad, and digging in.

The following day, August 19, brought Warren some support from the IX Corps, but a flank attack by Confederates under Gen. William Mahone scattered the Union men on that part of the field and again resulted in more captured blue coats.

August 20 saw little fighting due to the heavy rains. However, on August 21 Confederates again took to the offensive and attacked the Union left, not realizing the Yankees had dug in firmly along the railroad supported with significant artillery. The lion's share of the Confederate attack fell on Gen. Johnson Hagood's South Carolina brigade, which included the 11th, 21st, 25th, and 27th regiments. The Palmetto State men ran into a buzz saw and suffered terribly.

During the assault and its resulting melee, 22 year old Pvt. Frederick C. Anderson, Company A,18th Massachusetts Infantry (Gynn's Brigade, Griffin's Division) somehow was able to not only capture the 27th South Carolina's battleflag, but also the man carrying it. His citation simply reads: "Capture of the 27th South Carolina battle flag (C.S.A.) and the flag bearer." Anderson's life story is almost amazing as his heroic deed on August 21, 1864.

Born in Boston, Massachusetts in 1842, Frederick Anderson became an orphan as a young boy. The 1850 census shows Anderson as an "Inmate of the House of Industry" in Boston along with dozens of other poor boys and girls and men and women. In his early teens, Frederick was part of the "Orphan Train" that transported children out of the city of Boston to more rural parts of the state to work for families who needed help, while learning a trade or occupation. Frederick landed in the farming home of Stillman Wilbur in Raynham, Massachusetts. The 1860 census shows him there and lists his age a 14, apparently missing his true age by about 4 years.

Anderson enlisted in the 18th Massachusetts in August 1861 as a 19 year old private. He is noted as being 5 feet 3 inches tall. The 18th Massachusetts saw hard service, fighting in battles such as Second Manassas, Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, and the 1864 Overland Campaign. Anderson received his Medal of Honor only a few weeks after his courageous effort. When the 18th disbanded after its three years of service, Anderson reenlisted with the 32nd Massachusetts and continued the fight. Wounded in the foot in December 1864, he soon returned to action and was treated to a furlough for his reenlistment. Back with the army in time to witness Gen. Lee's surrender at Appomattox, Anderson mustered out in June 1865 with the 32nd Massachusetts.

After the war, Anderson married, had children, and enjoyed the family life he missed as a youth. Unexpectedly, Anderson died in 1882 at 40 years old while working on the railroad in Rhode Island. His grave was recently located in Dighton, Massachusetts, where he rests in peace; a former orphan, youthful Union soldier, Medal of Honor recipient, husband, father, and hero.

Saturday, December 14, 2019

How to Increase Your Chances of Getting a Good History Book

I've been thinking about sharing a few common sense tips for increasing your chances of getting a good history book for some time now. With the prices of published works rising every year it is important to spend one's money wisely by trying to get it right as often as possible when purchasing a book. So here goes:

1. Buy books from a familiar author.

When I read a book and enjoy it, I try to find other works by that particular author, especially if they are on related topics. Authors typically write in a certain style and style usually carries over from book to book, at least some extent.

2. Read book reviews.

Book reviews come from many different sources these days. Blogs, academic journals, even online sellers all offer reviews. However, in my opinion, not all reviews are created equal. I personally prefer book reviews written by academics or subject experts. They have been asked to write the book review because they, more often than not, know the historiography of that book's subject matter. They know if the historical arguments contained in the book are sound or if the author misses the mark.

3. Buy books from recognized publishers.

Publishers have reputations at stake. They typically have editors and peer readers work with authors as works are being revised during the writing process to ensure that the book is as error free as possible. That is not to say that all errors (both factual and interpretive) get caught before going to print, however, the chances are reduced. Self published works and publishers with lower standards often skip this all important step, to the disgust of the reader.

4. Share and request recommendations.

I usually post the book that I am currently reading on Facebook. I then often follow up by sharing my thoughts about it. This allows many of my reading friends to see what I am working on and ask questions about it. Sharing is caring! During conversations, ask friends what they are reading. They probably want give their thoughts as much as you want to hear them.

5. Mine the bibliography of books you enjoy.

This is probably the least fool safe suggestion here. Historians may use just a small part of a book, perhaps for a quote, and then cite it. They might have not even cited the book, but used it in attempt to better understand the topic they are covering, thus landing it in their bibliography. However when one finds a title from an author's bibliography that looks intriguing and then does some investigative work by reading a few reviews it may well prove to be a quality addition to one's library.

6. Create an online wish list.

If you are a big book enthusiast, I encourage you to create an online wish list. Friends and family know that I am an avid reader who likes to receive books as gifts. Instead of gambling on buying a book for me, they can review my wish list on Amazon to see a list of books that I've already investigated and wish to add to my collection. That way, when you open that wrapping paper, you don't have to fake a smile and lie by saying, "I've been wanting to read this!"

Hopefully these six ideas will help you improve your chances of getting a good history book. There are so many good books out there, and some duds too, but wasting one's time and money on bad books is not something anyone wants to do.

Thursday, December 12, 2019

"The Color of Uniforms."

I found this brief article in the May 23, 1861, Richmond, Indiana, Palladium newspaper. It warned that due to advances in rifled weapons or "arms of precision" as the author termed them, bright uniforms should be avoided. He cautioned, "and, when we dress a soldier in red, or even dark blue, we do the same thing, and in fact assist the enemy." At this early point in the war many of the Union militia units were still outfitted with grey and other earth-toned uniforms. Of course, the United States military ultimately decided against blending in and chose its standard light blue trousers and dark blue fatigue blouse. Some Indiana regiments totally ignored this advice in favor of flashy variations of Zouave uniforms.

I also found interesting the writer's comment that "Our Southern neighbors, who have been habituated to street fights and the use of weapons against each other, are prepared to take any advantage we may give them." It appears that the antebellum reputation for personal violence in the South was well established in Northern minds and at least carried over somewhat into the early days of the war.

Monday, November 25, 2019

Recent Acquisitions to My Library

It has been a while since I've listed some additions to my library, so I thought I'd get to it. My book purchasing has slowed over the past couple of months, but I've picked up a couple here and there, and I received a nice haul for my recent birthday.

Always looking for opportunities to increase my knowledge of aspects of the Civil War in eastern North Carolina, I found and purchased a copy of Time Full of Trial: The Roanoke Island Freedmen's Colony, 1862-1867 by Patricia C. Click. Along with the Tennessee and Cumberland River valleys, the Atlantic coast proved to be a region ripe for invasion by the Union army and navy. Places like Norfolk, Virginia, Port Royal, South Carolina, and Roanoke Island, North Carolina saw early military incursions, and doing so brought thousands of formerly enslaved refugees within Union lines. The refugee story is one that needs telling more often, so I'm looking forward to this particular study.

I've probably mentioned on here that I am always interested in reading anything that Dr. William J. Cooper authors or coauthors. I've been a big fan since reading his Liberty and Slavery: Southern Politics to 1860 long ago. So, I had a big smile on my face when I saw Approaching Civil War and Southern History among the books my wife bought me for my birthday. This fine book contains 10 essays that nearly span the distinguished career of Cooper. Good stuff!

I'm hooked on reading collections of Civil War soldiers' letters. There is simply no better way to learn about the experience of soldering than reading their own written words. I heard about Dear Ma, The Civil War Letters of Curtis Clay Pollock: First Defender & First Lieutenant 48th Pennsylvania Infantry this past summer and quickly put it on my wish list. Pollock's Civil War army career spanned from answering the Lincoln's first call to defend Washington D.C. to his death in the opening days of the Petersburg Campaign. This collection is sure to provide me with a fix for my obsession.

In my humble opinion, America's greatest challenge to realizing the ideals upon which the nation was founded is that of true racial equality. Although abolished with the 13th Amendment, slavery left a legacy on the United States that we are still dealing with today. As a friend of mine sometimes says, "Racism doesn't stop, it evolves." I firmly believe that a large first step toward eliminating racism is learning about its history. It is difficult history, but it is important history. A Long Dark Night: Race in America from Jim Crow to World War II by J. Michael Martinez covers America's troubles with race from the promise of Reconstruction, through the "nadir of race relations" at the turn of the 20th century, to the end of World War II.

I've truly enjoyed organizing a book club at work. Getting together with fellow readers and sharing one another's thoughts is a way for me to continue one of the joys I found in graduate school. Our small group is getting ready to start its fourth year in January and it has been so worth the time organizing it. The selection for our next meeting is Lincoln's Greatest Journey: Sixteen Days the Changed a Presidency, March 21-April 8, 1865 by Noah Andre Trudeau. This period included visits to the Petersburg front, so I'm especially eager to dig in.

Happy reading!

Monday, November 4, 2019

Just Finished Reading - They Were Her Property

I've been rather tardy in sharing my thoughts on some the books I've recently read. However, one of the most impressive of those selections is, They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South by Stephanie Jones-Rogers. In it, Jones-Rogers argues that Southern women were far greater direct participants in the "peculiar institution" than previously thought.

The system of coverture, which granted husbands rights to any property that wives brought into a marriage, has led some historians to overlook the not uncommon practice of parents willing daughters property for their "sole and separate" benefit and use. Parents of daughters knew that husbands too often squandered significant estates by mismanagement and bad habits like profligate buying/spending, gambling, and drinking. The parents wanted to provide whatever legal measures possible to protect the financial futures of their daughters and grandchildren. And since daughters many times received enslaved property rather than real estate property, the men, women, and children who passed to daughters were their primary sources of wealth. Jones-Rogers uncovers a significant amount of evidence through a multitude of different sources to show that not only did southern women in these situations view slaves as their "sole and separate" property, they often managed them differently than those that belonged to their husbands.

Many of the accounts that the author uses as evidence for these coverture-thwarting instances come from the WPA Slave Narratives of the 1930s. Sadly many of the slave narratives vividly show that within the slave regime, women could be just as harsh taskmasters of as any males.

Women also participated willingly in the slave trade, not so much as organized traders (which was overwhelming viewed as a male sphere), but Southern women pragmatically understood the system of buying and selling slaves as one that could enhance their wealth if managed properly. The same went for the renting/leasing of their human property. One facet of buying and renting that Jones-Rogers examines closely in a chapter is that of wet nursing. This situation, usually left to women due to its maternal nature, created situations in which white women controlled the motherhood of their enslaved women. White women who chose not to nurse their own children, or who were unable to produce milk, found wet nurses among the enslaved women of their communities, if not already among her own property. Obviously, little consideration or choice was given to the enslaved women who became additional commodities in these situations.

Jones-Rogers continues the examination of Southern women as slaveholder to the Civil War and emancipation. She persuasively explains how antebellum systems perpetuated Jim Crow realities in the decades after the war. From the book's epilogue the author states: "Former slave-owning women's deeper and more complex investments in slavery help explain why, in the years following the Civil War, they helped construct the South's system of racial segregation, a system premised, as was slavery, upon white supremacy and black oppression. Understanding the the direct economic investments white women made in slavery and their stake in its perpetuation, and recognizing the ways they benefited from their whiteness, helps us understand why they and many of their female descendants elected to uphold a white-supremacist order after slavery ended."

Engagingly written, They Were Her Property is a book that challenges us to think differently about the complexity of slavery and how interwoven it was into the white South's economy and society. I highly recommend it.

The system of coverture, which granted husbands rights to any property that wives brought into a marriage, has led some historians to overlook the not uncommon practice of parents willing daughters property for their "sole and separate" benefit and use. Parents of daughters knew that husbands too often squandered significant estates by mismanagement and bad habits like profligate buying/spending, gambling, and drinking. The parents wanted to provide whatever legal measures possible to protect the financial futures of their daughters and grandchildren. And since daughters many times received enslaved property rather than real estate property, the men, women, and children who passed to daughters were their primary sources of wealth. Jones-Rogers uncovers a significant amount of evidence through a multitude of different sources to show that not only did southern women in these situations view slaves as their "sole and separate" property, they often managed them differently than those that belonged to their husbands.

Many of the accounts that the author uses as evidence for these coverture-thwarting instances come from the WPA Slave Narratives of the 1930s. Sadly many of the slave narratives vividly show that within the slave regime, women could be just as harsh taskmasters of as any males.

Women also participated willingly in the slave trade, not so much as organized traders (which was overwhelming viewed as a male sphere), but Southern women pragmatically understood the system of buying and selling slaves as one that could enhance their wealth if managed properly. The same went for the renting/leasing of their human property. One facet of buying and renting that Jones-Rogers examines closely in a chapter is that of wet nursing. This situation, usually left to women due to its maternal nature, created situations in which white women controlled the motherhood of their enslaved women. White women who chose not to nurse their own children, or who were unable to produce milk, found wet nurses among the enslaved women of their communities, if not already among her own property. Obviously, little consideration or choice was given to the enslaved women who became additional commodities in these situations.

Jones-Rogers continues the examination of Southern women as slaveholder to the Civil War and emancipation. She persuasively explains how antebellum systems perpetuated Jim Crow realities in the decades after the war. From the book's epilogue the author states: "Former slave-owning women's deeper and more complex investments in slavery help explain why, in the years following the Civil War, they helped construct the South's system of racial segregation, a system premised, as was slavery, upon white supremacy and black oppression. Understanding the the direct economic investments white women made in slavery and their stake in its perpetuation, and recognizing the ways they benefited from their whiteness, helps us understand why they and many of their female descendants elected to uphold a white-supremacist order after slavery ended."

Engagingly written, They Were Her Property is a book that challenges us to think differently about the complexity of slavery and how interwoven it was into the white South's economy and society. I highly recommend it.

Saturday, November 2, 2019

Ran Away From My Farm, At the Half-Way House

Tomorrow marks one year wedded bliss for my wife and me. To help celebrate, I made dinner reservations at the Halfway House, a 1760s inn and tavern that happened to be situated "halfway" on the turnpike (and later railroad) between Richmond and Petersburg. I received a hearty recommendation from a friend that it would be a nice place for dinner for two history lovers. After I looked it up online to make the reservation, I remembered seeing a reference to it (or at least the area) in a runaway slave advertisement.

I combed through dozens of images that I have saved on my computer and finally located it. It ran in the August 20, 1864 issue of the Richmond Daily Dispatch. In it, owner J.M. Wolff seeks to have his slave Richard, "about twenty or twenty-one years old" and described as "black," apprehended. Although no specific dollar amount is listed for Richard's capture, Wolf promised to "pay a liberal reward."

A search through the 1860 census did not locate a J.M. Wolff in either Chesterfield County or Richmond (Henrico County). However, additional information contained within the notice did turn up some interesting corroborative findings.

Wolff explained in the advertisement that he purchased Richard from slave traders Lee and Bowman in Richmond, and that Richard was previously owned by Miss Margaret Bottom of Amelia Courthouse. I located Margaret Bottom in the 1860 census. She is listed as 23 years old and apparently living in the household of her mother, Lucy H. Bottom (45 years old), and with a brother, T. J. Bottom, a 22 year old farmer. Margaret Bottom is shown as owning $4,000 in personal property. Lucy Bottom owned $12,688 in personal property. Suspecting that most of those values were tied up in human property, I checked the slave schedules. My suspicions were confirmed. Mother Lucy Bottom is shown as owning 15 slaves. Brother T. J. Bottom is listed as owning six people, and M. P. (Margaret) Bottom owned five individuals. Margaret's enslaved property included one 23 year old black male, the only one among her group that closely fits the gender, age, and color description of Richard.

The advertisement also states that Richard had a wife near Amelia Courthouse and that may be where he was headed. In August 1864, both Richmond and Petersburg, as well as the Bermuda Hundred area where Wolff's farm was located were all under pressure from Union forces. And while it is certainly possible that Richard used the disruption of warfare to head to Amelia County to the west and his wife, his chances were probably best in reaching the Union troops under Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler's Army of the James at Bermuda Hundred, a number of whom were United States Colored Troops.

These advertisements tend to bring up a multitude of questions, most of them likely unanswerable. What motivated Margaret Bottom to sell Richard to slave traders? Where did Richard really go? Was he captured before he was able to realize freedom in the spring of 1865? What did he do for a living after the war? When did he die? Did he and his wife in Amelia County ever reunite? Did they have children? Where are Richard's descendants today? Do they know his story?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)