John C. Fremont and his abolitionist supporters are ridiculed. In particular, the artist condemns the Republican candidate's alliance with New York "Tribune" editor Horace Greeley and Henry Ward Beecher and Beecher's role in the Kansas-Nebraska conflict. Fremont (center) rides a scrawny "Abolition nag" with the head of Greeley. The horse is led toward the left and "Salt River" (i.e., political doom) by prominent New York politician William Seward. Fremont muses hopefully, "This is pretty hard riding but if he only carries me to the White house in safety I will forgive my friends for putting me astride of such a crazy Old Hack." Greeley: "Seward it seems to me we are going the same Road we did in 'fifty two' but as long as you lead I'll follow if I go it blind." Seward: "Which ever road I travel always brings me to this confounded river, I thought we had a sure thing this time on the Bleeding Kansas dodge." On the right stands radical abolitionist minister Henry Ward Beecher, laden with rifles. He preaches in verse: "Be heavenly minded my bretheren all / But if you fall out at trifles; / Settle the matter with powder and ball / And I will furnish the rifles. Beecher was linked to the New England Emigrant Aid Society, and was known to have furnished antislavery emigrants with arms to participate in the struggle between proslavery and antislavery settlers in Kansas. A frontiersman (far right), a figure from Fremont's exploring past, leans on his rifle and comments, "Ah! Colonel!--you've got into a bad crowd--you'll find that dead Horse on the prarie, is better for the Constitution, than Abolition Soup or Wooly head stew in the White House."

Thursday, May 31, 2012

John C. Fremont and 1856 Election Cartoon

John C. Fremont and his abolitionist supporters are ridiculed. In particular, the artist condemns the Republican candidate's alliance with New York "Tribune" editor Horace Greeley and Henry Ward Beecher and Beecher's role in the Kansas-Nebraska conflict. Fremont (center) rides a scrawny "Abolition nag" with the head of Greeley. The horse is led toward the left and "Salt River" (i.e., political doom) by prominent New York politician William Seward. Fremont muses hopefully, "This is pretty hard riding but if he only carries me to the White house in safety I will forgive my friends for putting me astride of such a crazy Old Hack." Greeley: "Seward it seems to me we are going the same Road we did in 'fifty two' but as long as you lead I'll follow if I go it blind." Seward: "Which ever road I travel always brings me to this confounded river, I thought we had a sure thing this time on the Bleeding Kansas dodge." On the right stands radical abolitionist minister Henry Ward Beecher, laden with rifles. He preaches in verse: "Be heavenly minded my bretheren all / But if you fall out at trifles; / Settle the matter with powder and ball / And I will furnish the rifles. Beecher was linked to the New England Emigrant Aid Society, and was known to have furnished antislavery emigrants with arms to participate in the struggle between proslavery and antislavery settlers in Kansas. A frontiersman (far right), a figure from Fremont's exploring past, leans on his rifle and comments, "Ah! Colonel!--you've got into a bad crowd--you'll find that dead Horse on the prarie, is better for the Constitution, than Abolition Soup or Wooly head stew in the White House."

Monday, May 28, 2012

A Return to Roots

Last weekend I had the pleasure of visiting the location of some of my roots on my father's side of the family. Parts of my family have been in Clinton County, Kentucky for over two hundred years, so it was nice to go back, see the sites and visit with some of my relatives. Of course, I have always looked for connections that my family had with the Civil War era, and in an an area like the Tennessee-Kentucky border one doesn't have to look too hard to find them. Here, warfare resembled that as was fought in Missouri, where neighbor fought neighbor and pre-war grievances were used as excuses to eliminate enemies.

Probably the most noted Civil War figure in the area was Confederate guerrilla Champ Ferguson. Ferguson was born in Clinton County and was known as a rough and tough figure in the area. Despite most of his family choosing the Union, Champ chose the South and during the war became a terror to citizens that proclaimed any sympathy for the Federal cause. He moved to White County, Tennessee near the start of the conflict, but spent much of the war in region of his birth, hunting down those he believed were trying to kill him. He was convicted in Nashville at the close of the war for over 50 murders and was hanged.

My great great grandfather George Washington Boles's grave is in Cedar Hill Cemetery, east of Albany, Kentucky. George was born just over the state line in Overton County, Tennessee in 1845 the son of John Boles, a former state representative and senator, and Matilda Beaty Boles, sister to Unionist scout (some say guerrilla) "Tinker" Dave Beaty. George rode with his uncle David Beaty during the Civil War as they fought against Confederate guerrillas such as Ferguson. George was apparently wounded in the hand during one of their fights with Ferguson's men, but in the end he lived a long life; he died in 1941. I remember coming to Cedar Hill as a child when my brother and I would spend summer visits our grandparents, but I don't think I had been back in over thirty years.

The Clinton County Courthouse was only one of a number of local government buildings in the Tennessee-Kentucky borderland that was set to flame. It was burned by Confederate guerrillas near the end of the Civil War. It is sad to think how much history was destroyed and went up in smoke with the building.

This interesting highway marker on the Clinton County Courthouse lawn shows the locations of courthouses around the state that were burned. Of special note was the burning spree during John Bell Hood's Tennessee Campaign by Confederate cavalry general Hylan Lyon's men. Lyon was one of Nathan Bedford Forrest's subordinates and his path of conflagration is marked with red arrows.

As mentioned above, part of my paternal grandmother's family was located in Overton County (what later became Pickett County) Tennessee. During my visit last weekend I drove down to Livingston, the county seat of Overton County. I had hoped to find out some more information on George Washington Boles's father, John Boles. While I was disappointed to find that the Overton County Courthouse too had been burned by Kentucky Confederate guerrillas and many of the records destroyed, I did find out some interesting information that I will share in a later post after some more research.

This state-border region was ripe with divided sentiment. The best witness to this divisiveness is the 1861 Tennessee referendum on secession that was held on June 8, 1861. In that vote Overton County overwhelmingly voted to secede 1,471 (80.2%) to 364 (19.8%), however, their next-door county to the east, Fentress County, polled overwhelmingly the opposite; 128 (16.4%) for secession and 651 (83.6%) against.

Also of note for Clinton County is that it was the birthplace of Kentucky Civil War governor (1863-1867) Thomas Bramlette (pictured above). Bramlette, born in 1817, studied law as a young man in Louisville and then returned to Clinton County and won a seat in the Kentucky legislature. He also served as the commonwealth's attorney during Governor John J. Crittenden's administration in the 1840s. Just before the Civil War he was a district judge. Judge Bramlette accepted a colonel's commission in the 3rd Kentucky Infantry, but resigned in the summer of 1862 and became district attorney for Kentucky. Chosen as governor in the fall of 1863, Bramlette, like most Kentuckians, vehemently opposed African American enlistments. His Lt. governor Richard T. Jacob was actually exiled to the South for his strident opposition to the Lincoln administration. After the war the conservative Bramlette pardoned many of the state's Confederates, supported the 13th amendment as he saw slavery as good as dead due to the war, but opposed the 14th and 15th amendments and the Freedmen's Bureau's involvement in the state.

Friday, May 25, 2012

"The Wildest Excitement Has Prevailed"

On May 29, 1864, Fourth District Provost Marshal Captain Jame Fidler filed a report to Assistant Adjutant General E.D. Townsend on outrages committed against African Americans enlisted or attempting to enlist as soldiers for the Union army. He opened his report stating, "The citizens of the fourth congressional district have been for some time very much infuriated against the authorities for the enlistment of negroes without the consent of the master."

He itemized a list of "acts" that he saw as "directly contrary to the spirit of the law authorizing enlistments" and General Order 42 issued May 14, 1864.

"1. Before a negro could enlist without his master's consent, one presented himself to the deputy provost marshal at Columbia [Kentucky] for enlistment. The law was explained to the boy and he started home. The citizens were not satisfied with this, but followed him to woods and severely whipped him. I immediately ordered an investigation. The parties could not be found! and it was declared by disinterested parties to be only justice to the negro, since he had "sassed" his owner.

2. Fifteen negroes from Green and Taylor counties applied to my headquarters for the purpose of enlisting; they had not the consent of their owners, and under their existing orders I could not receive them. I explained the law to them; gave them to understand that I would protect and enlist them as soon as they obtained the proper consent. They left my headquarters, were captured in Lebanon by four young men, assisted by a crowd of men and boys, and were severely whipped. I immediately arrested the parties, although I was threatened with a mob if i did it. The case was promptly reported, and the young men, after a time, released until further orders.

3. In the county of Green, serious threats were made against the deputy provost marshal, and men announced that the enlistment should cease.

4. In Taylor county, negroes were whipped, thrown in jail, and in other ways deterred from enlisting.

5. In LaRue county, a special agent was captured and nearly killed by guerrilla citizens.

6. In Hardin, the deputy provost marshal has not been able to enlist or send negroes to these headquarters because of the information of citizens.

7. In Spencer county the deputy provost marshal was beaten and run out of his county. Excitement in Casey county caused the citizens of Casey to tear down posters sent out by the deputy provost marshal.

In truth, in almost every county in the district the wildest excitement has prevailed; only fears have prevented an outbreak. I have acted as carefully as possible, and at the same time have attempted to prevent all outbreaks. In recruiting negroes I have acted in precise accordance with the law and orders, but an intense feeling has ever existed against the law."

He itemized a list of "acts" that he saw as "directly contrary to the spirit of the law authorizing enlistments" and General Order 42 issued May 14, 1864.

"1. Before a negro could enlist without his master's consent, one presented himself to the deputy provost marshal at Columbia [Kentucky] for enlistment. The law was explained to the boy and he started home. The citizens were not satisfied with this, but followed him to woods and severely whipped him. I immediately ordered an investigation. The parties could not be found! and it was declared by disinterested parties to be only justice to the negro, since he had "sassed" his owner.

2. Fifteen negroes from Green and Taylor counties applied to my headquarters for the purpose of enlisting; they had not the consent of their owners, and under their existing orders I could not receive them. I explained the law to them; gave them to understand that I would protect and enlist them as soon as they obtained the proper consent. They left my headquarters, were captured in Lebanon by four young men, assisted by a crowd of men and boys, and were severely whipped. I immediately arrested the parties, although I was threatened with a mob if i did it. The case was promptly reported, and the young men, after a time, released until further orders.

3. In the county of Green, serious threats were made against the deputy provost marshal, and men announced that the enlistment should cease.

4. In Taylor county, negroes were whipped, thrown in jail, and in other ways deterred from enlisting.

5. In LaRue county, a special agent was captured and nearly killed by guerrilla citizens.

6. In Hardin, the deputy provost marshal has not been able to enlist or send negroes to these headquarters because of the information of citizens.

7. In Spencer county the deputy provost marshal was beaten and run out of his county. Excitement in Casey county caused the citizens of Casey to tear down posters sent out by the deputy provost marshal.

In truth, in almost every county in the district the wildest excitement has prevailed; only fears have prevented an outbreak. I have acted as carefully as possible, and at the same time have attempted to prevent all outbreaks. In recruiting negroes I have acted in precise accordance with the law and orders, but an intense feeling has ever existed against the law."

Thursday, May 24, 2012

Just Finished Reading

One aspect of slavery that has recently drawn my attention in reading material is that of the domestic slave trade. The purchasing and large-scale interstate movement and transportation of bondsmen in the United States has a historiography that goes back to the first significant studies of slavery and has been conflicted in interpretations.

Professor Michael Tadman jumped into the debate with this book, Speculators and Slaves: Masters, Traders, and Slaves in the Old South, back in 1989. Tadman utilized a wide range of primary sources as evidence to form his interpretation. Among other sources, he tapped census materials, newspaper reports, traveler accounts, court records, slave narratives, and most importantly, slave dealers' records and manuscript sources.

Speculators and Slaves is divided into two parts of which Tadman attacks longstanding myths on the domestic slave trade. The first part, "An Almost Endless Outgoing of Slaves: The Extent and Character of the Trading Business" covers the extent of the slave trade. Here the author claims that sale of slaves by individuals to traders was much more extensive than previously thought and the stigma of separating slave family members was not as taboo as it came to be seen in the post-emancipation era. For slaveholding people that sought to make money, the quickest way to raise it was to sell their slaves to a trader. These sales, Tadman contends, had a larger impact on the major shift in African American population figures from the East and Upper South to the Deep South rather than planter migrations, who brought their slaves with them.

The second part, "Slave Trading and the Values of Masters and Slaves," explains that racist assumptions were largely the means by which owners justified separating families. Black slaves were viewed by many whites, both North and South, as unable to develop deep loving and attached relationships. These racist views claimed that husbands and wives that were separated in sales would be upset at first, but that feeling would soon pass and they would find another mate. The same argument was made for children being sold from parents. It is this similar idea that continues to confound me when expressed by those present-day people who view slavery as a benign institution. To me it doesn't matter how kind a master was, it is the fact that the slave had no free will; he had no say or self-decision making ability to control his own life; he did not profit from his labor - another person did.

Another myth that Tadman attacks is that the slave trader was a community pariah. Sure there were plenty of slovenly, seedy and slimy speculators, who sold damaged goods and stole their stock, but the majority of the traders appear to have been well respected and appreciated members of their communities. Again, this myth appears to have arisen in the post-emancipation era when former owners wished to deflect a share of the blame. Many of these men, who also often had their hands in other community businesses, were viewed by their contemporaries - especially those it the Deep South states with an insatiable demand for stock - as necessary to their livelihood and a vital supplier of labor.

Tadman backs up his contentions with a dizzying array tables, charts and statistics, but unfortunately to me, they were at times difficult to decipher and fuzzy in their calculations. With that said, I still found Speculators and Slaves to be an informative and educational book. On a scale of 1 to 5, I give it a 4.5.

Professor Michael Tadman jumped into the debate with this book, Speculators and Slaves: Masters, Traders, and Slaves in the Old South, back in 1989. Tadman utilized a wide range of primary sources as evidence to form his interpretation. Among other sources, he tapped census materials, newspaper reports, traveler accounts, court records, slave narratives, and most importantly, slave dealers' records and manuscript sources.

Speculators and Slaves is divided into two parts of which Tadman attacks longstanding myths on the domestic slave trade. The first part, "An Almost Endless Outgoing of Slaves: The Extent and Character of the Trading Business" covers the extent of the slave trade. Here the author claims that sale of slaves by individuals to traders was much more extensive than previously thought and the stigma of separating slave family members was not as taboo as it came to be seen in the post-emancipation era. For slaveholding people that sought to make money, the quickest way to raise it was to sell their slaves to a trader. These sales, Tadman contends, had a larger impact on the major shift in African American population figures from the East and Upper South to the Deep South rather than planter migrations, who brought their slaves with them.

The second part, "Slave Trading and the Values of Masters and Slaves," explains that racist assumptions were largely the means by which owners justified separating families. Black slaves were viewed by many whites, both North and South, as unable to develop deep loving and attached relationships. These racist views claimed that husbands and wives that were separated in sales would be upset at first, but that feeling would soon pass and they would find another mate. The same argument was made for children being sold from parents. It is this similar idea that continues to confound me when expressed by those present-day people who view slavery as a benign institution. To me it doesn't matter how kind a master was, it is the fact that the slave had no free will; he had no say or self-decision making ability to control his own life; he did not profit from his labor - another person did.

Another myth that Tadman attacks is that the slave trader was a community pariah. Sure there were plenty of slovenly, seedy and slimy speculators, who sold damaged goods and stole their stock, but the majority of the traders appear to have been well respected and appreciated members of their communities. Again, this myth appears to have arisen in the post-emancipation era when former owners wished to deflect a share of the blame. Many of these men, who also often had their hands in other community businesses, were viewed by their contemporaries - especially those it the Deep South states with an insatiable demand for stock - as necessary to their livelihood and a vital supplier of labor.

Tadman backs up his contentions with a dizzying array tables, charts and statistics, but unfortunately to me, they were at times difficult to decipher and fuzzy in their calculations. With that said, I still found Speculators and Slaves to be an informative and educational book. On a scale of 1 to 5, I give it a 4.5.

Monday, May 21, 2012

Sherman Responds to McCook: "Send Them Away"

Sherman responded three days later to McCook. Instead of approving of his subordinate's plan to put the runaway slaves to work, Sherman explained that "the laws of the state of Kentucky are in full force" and that there were two options. Number 1, the slaves can be returned to their masters or their agents (overseers or slave catchers) or number 2, they can be sent to the county sheriff. But whatever, "you should not let them take refuge in Camp." Doing so could cause Kentucky Unionist slaveholders to abandon the Union.

Sherman closed by telling McCook that the slaves' that came to him were not to be believed and that "you will send them away."

Here's the response in its entirety:

I know it is almost impossible for you to ascertain in any case the owner of the negro, but so it is, his word is not taken in evidence and you will send them away I am yours

Sherman closed by telling McCook that the slaves' that came to him were not to be believed and that "you will send them away."

Here's the response in its entirety:

Louisville Kenty Nov 8, 1861

Sir I have no instructions from Government on the subject of Negroes, my opinion is that the laws of the state of Kentucky are in full force and that negroes must be surrendered on application of their masters or agents or delivered over to the sheriff of the County. We have nothing to do with them at all and you should not let them take refuge in Camp. It forms a source of misrepresentation by which Union men are estranged from our CauseI know it is almost impossible for you to ascertain in any case the owner of the negro, but so it is, his word is not taken in evidence and you will send them away I am yours

W. T. Sherman

Sherman image courtesy Library of Congress

Sunday, May 20, 2012

Gen. McCook Asks What to do with Kentucky Runaways

In November 1861, long before the U.S. Army had developed an official plan on what to do with runaway slaves in Kentucky, Brigadier General Alexander McDowell McCook wrote from Camp Nevin, Kentucky (pictured above from Harper's Weekly) to his Department of the Cumberland commander, William Tecumseh Sherman, for advice on what to do with the blacks that flocked to his camp seeking freedom.

To McCook these runaways were an annoyance and definite cause for concern in that in his thinking the slaves' fleeing may cause Kentucky to secede. But, the runaways were apparently a useful annoyance as he put promptly put them to work.

Camp Nevin Kentucky November 5th 1861

General: The subject of Contraband negros is one that is looked to, by the Citizens of Kentucky of vital importance Ten have come into my Camp within as many hours, and from what they say, there will be a general Stampeed of slaves from the other side of Green River– They have already become a source of annoyance to me, and I have great reason to belive that this annoyance will increase the longer we stay– They state the reasons of their running away–there masters are rank Secessionists, in some cases are in the rebel army–and that Slaves of union men are pressed into service to drive teams &&c

I would respectfully suggest that if they be allowed to remain here, that our cause in Kentucky may be injured– I have no faith in Kentucky's loyalty, there-for have no great desire to protect her pet institution Slavery– As a matter of policy, how would it do, for me to send for their master's and diliver the negro's–to them on the out-side of our lines, or send them to the other side of Green River and deliver them up– What effect would it have on our cause south of the River– I am satisfied they bolster themselves up, by making the uninformed believe that this is a war upon African slavery– I merely make these suggestions, for I am very far from wishing these recreant masters in possession of any of their property–for I think slaves no better than horses in that respect–

I have put the negro's to work– They will be handy with teams, and generally useful. I consider the subject embarrassing and must defer to your better judgement

. . . .

The negros that came to me to day state that their master's had notified them to be ready to go south with them on Monday Morning, and they left Sunday night–

. . . .

A. McD. McCook

McCook image courtesy of Library of Congress

Saturday, May 19, 2012

Just Finished Reading

This book, the Pulitzer Prize winner for history in 2011 is yet another fantastic read from Columbia University professor Eric Foner. I have enjoyed every Foner book I have read; with his Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party before the Civil War and Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution being especially outstanding. The Fiery Trial follows his previous works well.

As we all know, just about every facet of Lincoln's life and legacy has been covered by historians. Certainly other books have previously appeared that examined Lincoln's views on slavery and race. And, these works have taken just about every perspective, from those that purport Lincoln's unrealistic benevolence to works like Lerone Bennett's Forced into Glory, which takes Lincoln to task for not doing more sooner for African Americans. The Fiery Trial seems to be a much more balanced approach than most of these previous works covering Lincoln on slavery and race.

I think our nation's current politicians could lean a lesson from Lincoln. It seems that it is unpopular to change one's ideas on issues. It seems that to evolve in one's understanding, a hopefully natural process as one learns and experiences is disdained. It seems that one must stand in the same position on political issues or it is seen as a great weakness. To me this is a shame. I am personally glad that I have developed a better understanding of history as I have read, studied and learned, and as I have, my ideas on historical events have changed. Foner attempts to show that Lincoln, like almost all men of his era had certain racial prejudices that were difficult to shake off, but that he grew and evolved throughout his lifetime to quite an enlightened position on race by the time of his assassination.

Lincoln found himself in the unenviable position of being a moderate in a rather new political party. The radicals of the Republican Party wanted him to do more to rid the country of slavery while the conservatives of the party thought he was moving too quickly. Additionally, Unionist conservatives - mainly Democrats, many in the border states - but also those in states like Ohio, Pennsylvania and New Jersey made life difficult for Lincoln to push through war-time race-related legislation that he believed would help end the war and reunite the nation. When Lincoln attempted to end slavery in the border states, he started with tiny Delaware, but was promptly rebuffed. This Delaware failure factored into his not including the border states in his later Emancipation Proclamation. Kentucky and the other border states come in for their fair share of coverage in The Fiery Trial. Kentucky, even gets named in the chapter six title; "'I Must Have Kentucky': The Border Strategy."

Foner's second to last paragraph of the book sums up this work well. "Lincoln did not enter the White House expecting to preside over the destruction of slavery. A powerful combination of events, as we have seen, propelled him down the road to emancipation and then to reconsideration of the place blacks would occupy in a post-slavery America. Of course, the unprecedented crisis in which, as one member of Congress put it, 'the events of an entire century transpire in a year,' made change the order of the day. Yet as the presidency of his successor demonstrated, not all men placed in a similar situation possessed the capacity for growth, the essence of Lincoln's greatness. 'I think we have reason to thank God of Abraham Lincoln,' the abolitionist Lydia Maria Child wrote one week before his death. 'With all his deficiencies, it must be admitted that he had grown continuously; and considering how slavery had weakened and perverted the moral sense of the whole country, it was great good luck to have the people elect a man who was willing to grow.'"

On a scale of 1 to 5, I give A Fiery Trial a 4.75.

As we all know, just about every facet of Lincoln's life and legacy has been covered by historians. Certainly other books have previously appeared that examined Lincoln's views on slavery and race. And, these works have taken just about every perspective, from those that purport Lincoln's unrealistic benevolence to works like Lerone Bennett's Forced into Glory, which takes Lincoln to task for not doing more sooner for African Americans. The Fiery Trial seems to be a much more balanced approach than most of these previous works covering Lincoln on slavery and race.

I think our nation's current politicians could lean a lesson from Lincoln. It seems that it is unpopular to change one's ideas on issues. It seems that to evolve in one's understanding, a hopefully natural process as one learns and experiences is disdained. It seems that one must stand in the same position on political issues or it is seen as a great weakness. To me this is a shame. I am personally glad that I have developed a better understanding of history as I have read, studied and learned, and as I have, my ideas on historical events have changed. Foner attempts to show that Lincoln, like almost all men of his era had certain racial prejudices that were difficult to shake off, but that he grew and evolved throughout his lifetime to quite an enlightened position on race by the time of his assassination.

Lincoln found himself in the unenviable position of being a moderate in a rather new political party. The radicals of the Republican Party wanted him to do more to rid the country of slavery while the conservatives of the party thought he was moving too quickly. Additionally, Unionist conservatives - mainly Democrats, many in the border states - but also those in states like Ohio, Pennsylvania and New Jersey made life difficult for Lincoln to push through war-time race-related legislation that he believed would help end the war and reunite the nation. When Lincoln attempted to end slavery in the border states, he started with tiny Delaware, but was promptly rebuffed. This Delaware failure factored into his not including the border states in his later Emancipation Proclamation. Kentucky and the other border states come in for their fair share of coverage in The Fiery Trial. Kentucky, even gets named in the chapter six title; "'I Must Have Kentucky': The Border Strategy."

Foner's second to last paragraph of the book sums up this work well. "Lincoln did not enter the White House expecting to preside over the destruction of slavery. A powerful combination of events, as we have seen, propelled him down the road to emancipation and then to reconsideration of the place blacks would occupy in a post-slavery America. Of course, the unprecedented crisis in which, as one member of Congress put it, 'the events of an entire century transpire in a year,' made change the order of the day. Yet as the presidency of his successor demonstrated, not all men placed in a similar situation possessed the capacity for growth, the essence of Lincoln's greatness. 'I think we have reason to thank God of Abraham Lincoln,' the abolitionist Lydia Maria Child wrote one week before his death. 'With all his deficiencies, it must be admitted that he had grown continuously; and considering how slavery had weakened and perverted the moral sense of the whole country, it was great good luck to have the people elect a man who was willing to grow.'"

On a scale of 1 to 5, I give A Fiery Trial a 4.75.

Wednesday, May 16, 2012

Loguen Responds to Former Master

Thank goodness Jermain Loguen had the nerve to respond to his former mistress's letter, otherwise we would be left to speculate what he thought about her pent-up sentiments in the two plus decades that had passed since he had fled bondage.

As one might image Loguen's response letter is harsh and bitter, especially as it concerns her attempt to extort money from him for his escape. He too heaps scorn upon his father, Manasseth Logue, who Loguen assumes has since died, but remembered the "sins against my poor family." I will leave it to him to express:

As one might image Loguen's response letter is harsh and bitter, especially as it concerns her attempt to extort money from him for his escape. He too heaps scorn upon his father, Manasseth Logue, who Loguen assumes has since died, but remembered the "sins against my poor family." I will leave it to him to express:

SYRACUSE, N. Y., March 28, 1860.

MRS. SARAH

LOGUE:--Yours of the 20th of February is duly received, and I thank you for it.

It is a longtime since I heard from my poor old mother, and I am glad to know

she is yet alive, and as you say, "as well as common." What that

means I don't know. I wish you had said more about her.

You are a woman; but

had you a woman's heart you could never have insulted a brother by telling him

you sold his only remaining brother and sister, because he put himself beyond

your power to convert him into money.

You sold my brother and

sister, ABE and ANN, and 12 acres of land, you say, because I run away. Now you

have the unutterable meanness to ask me to return and be your miserable

chattel, or in lieu thereof send you $1,000 to enable you to redeem

the land, but not to redeem my poor brother and sister! If I were to

send you money it would be to get my brother and sister, and not that you

should get land. You say you are a cripple, and doubtless you say it

to stir my pity, for you know I was susceptible in that direction. I do pity

you from the bottom of my heart. Nevertheless I am indignant beyond the power

of words to express, that you should be so sunken and cruel as to tear the

hearts I love so much all in pieces; that you should be willing to impale and

crucify us out of all compassion for your

poor foot or leg. Wretched woman! Be it known to you that I

value my freedom, to say nothing of my mother, brothers and sisters, more than

your whole body; more, indeed, than my own life; more than all the lives of all

the slaveholders and tyrants under Heaven.

You say you have offers

to buy me, and that you shall sell me if I do not send you $1,000, and in the

same breath and almost in the same sentence, you say, "you know we raised

you as we did our own children." Woman, did you raise your own

children for the market? Did you raise them for the whipping-post? Did you

raise them to be drove off in a coffle in chains? Where are my poor bleeding

brothers and sisters? Can you tell? Who was it that sent them off into sugar

and cotton fields, to be kicked, and cuffed, and whipped, and to groan and die;

and where no kin can hear their groans, or attend and sympathize at their dying

bed, or follow in their funeral? Wretched woman! Do you say you did

not do it? Then I reply, your husband did, and you approved the

deed--and the very letter you sent me shows that your heart approves it all.

Shame on you.

But, by the way, where

is your husband? You don't speak of him. I infer, therefore, that he is dead;

that he has gone to his great account, with all his sins against my poor family

upon his head. Poor man! gone to meet the spirits of my poor, outraged and

murdered people, in a world where Liberty and Justice are MASTERS.

But you say I am a

thief, because I took the old mare along with me. Have you got to learn that I

had a better right to the old mare, as you called her, than MANASSETH LOGUE had

to me? Is it a greater sin for me to steal his horse, than it was for him to

rob my mother's cradle and steal me? If he and you infer that I forfeit all my

rights to you, shall not I infer that you forfeit all your rights to me? Have

you got to learn that human rights are mutual and reciprocal, and if you take

my liberty and life, you forfeit me your own liberty and life? Before God and

High Heaven, is there a law for one man which is not law for every other man?

If you or any other

speculator on my body and rights, wish to know how I regard my rights, they

need but come here and lay their hands on me to enslave me. Did you think to

terrify me by, presenting the alternative to give my money to you, or give my

body to Slavery? Then let me say to you, that I meet the proposition with

unutterable scorn and contempt. The proposition is an outrage and an insult. I

will not budge one hair's breadth. I will not breath a shorter breath, even to

save me from your persecutions. I stand among a free people, who, I thank God,

sympathize with my rights, and the rights of mankind; and if your emissaries

and venders come here to re-inslave me, and escape the unshrinking vigor of my

own right arm, I trust my strong and brave friends, in this City and State,

will be my rescuers and avengers.

Yours, &c.,

J. W. Loguen.

Tuesday, May 15, 2012

A Master's Letter to a Former Slave

Jermain Loguen was born in 1813 to his slave mother Cherry, and white master father David Logue. He was thought to be just another slave when he escaped from Logue's Davidson County, Tennessee farm in 1834, but he would prove that with the opportunity of freedom, he was anything but common. After making his way to Canada he moved to New York state in the 1840s. He eventually became a teacher and an African Methodist Episcopal Zion preacher, as well as a shrewd real estate investor. While living in Syracuse, Loguen became active in Underground Railroad operations and frequently spoke out against slavery. In 1859 he published his biography, The Rev. J.W. Loguen, as a Slave and as a Freeman, A Narrative of a Real Life.

Loguen's former master, Sarah Logue most likely heard about or read his book and wrote to Jermain in Syracuse asking him to pay $1000 for his freedom - 26 years after he ran away. It is interesting that Mrs. Logue basically calls Loguen a thief for running away (stealing himself), but does not see that while he was a slave his labor was being stolen. The Abe and Ann mentioned in the letter were Jermain's brother and sister.

MAURY Co., STATE of TENNESSEE,

February 20th, 1860.

To JARM:--I now take my

pen to write you a few lines, to let you know how we all are. I am a cripple,

but I am still able to get about. The rest of the family are all well. Cherry

is as well as common. I write you these lines to let you know the situation we

are in--partly in consequence of your running away and stealing Old Rock, our

fine mare. Though we got the mare back, she was never worth much after you took

her; and as I now stand in need of some funds, I have determined to sell you;

and I have had an offer for you, but did not see fit to take it. If you will

send me one thousand dollars and pay for the old mare, I will give up all claim

I have to you. Write to, me as soon as you get these lines, and let me know if

you will accept my proposition. In consequence of your running away, we had to

sell Abe and Ann and twelve acres of land; and I want you to send me the money

that I may be able to redeem the land that you was the cause of our selling,

and on receipt of the above named sum of money, I will send you your bill of

sale. If you do not comply with my request, I will sell you to some one else,

and you may rest assured that the time is not far distant when things will be

changed with you. Write to me as soon as you get these lines. Direct your

letter to Bigbyville, Maury County, Tennessee. You had better comply with my

request.

I understand that you

are a preacher. As the Southern people are so bad, you had better come and

preach to your old acquaintances. I would like to know if you read your Bible?

If so can you tell what will become of the thief if he does not repent? and, if

the blind lead the blind, what will the consequence be? I deem it unnecessary

to say much more at present. A word to the wise is sufficient. You know where

the liar has his part. You know that we reared you as we reared our own

children; that you was never abused, and that shortly before you ran away, when

your master asked you if you would like to be sold, you said you would not

leave him to go with any body.

SARAH LOGUE.

Monday, May 14, 2012

Kentucky Lt. Gov. Richard T. Jacob, A Seeming Enigma

One reason history is so fascinating to me is because of the questions it raises. I probably spend too much time pondering why things happened they way they did. One question I am currently trying to answer is, why would a man so opposed to emancipation and African American soldiers serving in the Union army, seemingly willfully pardon a man convicted - not once but twice - with helping slaves run away.

The man I refer to is Richard Taylor Jacob (see my March 26, 2011 post). Jacob was the running mate Lt. Governor in 1863 when Thomas Bramlette was elected as Kentucky's chief executive. Before that he was colonel of the 9th Kentucky Cavalry (USA), although the pictured recruiting poster shows his attempt to raise an infantry regiment - yet another question I would like to answer. During the first years of the war Jacob and the 9th patrolled the state and chased John Hunt Morgan's raiders. Previous to the Civil War Jacob served with his brother-in-law by marriage and first Republican presidential candidate (1856) John C. Fremont in California. Jacob's marriage to Sarah Benton, daughter of powerful Missouri senator Thomas Hart Benton, only added to his family connections. He was also related to Zachary Taylor and his sister married a son of the "Great Compromiser" Henry Clay.

So, back to the question at hand: why would a strict conservative, opposed to emancipation and black soldiers, go out of his way to pardon Calvin Fairbank a known abolitionist and slave thief?

To provide you with some more information, I will rely heavily on Fairbank's memoir, Rev. Calvin Fairbank during Slavery Times: How He Fought the Good Fight to Prepare the Way, published in 1890. In the book Fairbank states that when Bramlette and Jacob were elected, "That was my daylight! I well knew that they would be elected, and the first time Bramlette was called away (and that would probably be soon), Jacob would pardon me as lieutenant and acting governor of the state." Fairbank claims that Jacob was "a good friend to me, and believed my conviction illegal." Why would Jacob think Fairbank was convicted illegally?

Fairbank's first offense was when he and Delia Webster helped Lewis Hayden and family escape from Lexington in 1844. For his efforts he received a 15 year sentence that was reduced to five years and was released in 1849. He was caught again when he tried to help a female Louisville slave escape to Indiana in 1851. For this second offense he received another 15 year sentence. He languished in the Kentucky State Penitentiary in Frankfort, where he was often abused for his abolitionist sentiments, until Jacob's pardon in 1863.

Fairbank doesn't go into much detail about what prompted Jacob to pardon him. He stated, "Richard T. Jacob, Lieutenant Governor, had been committed to my favor for years: he had said to me before the war: 'If I was Governor, I would turn you out today.' He was the son of John I. Jacob of Louisville and the son-in-law of Thomas H. Benton of Missouri. So that he was related to, and inherited good blood." O.K., that relationship and blood stuff is all well and good, but I want to know why Jacob was "committed to" Fairbank's "favor." He continued in his memoir that people had been pleading on his behalf to be released, including General James Harlan. Did he mean John Marshall Harlan, who was a colonel in the Civil War, or did he mean James Harlan, John's father, who I don't think was ever in a military role. Anyway, Fairbank continued, "I was anxious for Bramlette's absence for a while, that Jacob might hold the helm for a few hours; for Bramlette refused to interfere. I knew Jacob would." How did he know Jacob would, other than what Jacob had possibly told him before the war?

Fairbank's next sentence is especially confusing considering Jacob's expressed racist leanings. "The time had at last arrived when the people and government could see distinctly that it was the Africo-American's war: - that as he went, we went; as we went, he went:- we must both go together." This doesn't sound at all like the Jacob that railed against Lincoln, the Emancipation Proclamation and black soldiers. "President Lincoln had sent General [Speed] Fry to Kentucky with orders to enroll all the African people:-slave, free - male, female, - old, young; and the men competent for military service separately. Governor Bramlette forbade it. Fry reported to the President. Then was opened a discussion over the wires for several days. I watched this as my forlorn hope." Bramlette was ordered to Washington to speak to Lincoln and Fairbank got his fondest wish. Jacob came to the prison and said to the abolitionist, "How are you Fairbank? Well, I'm going to turn you out. Sneed, get up a little petition to knock the blows off me. I'm going to turn him out anyway." Fairbank asked Jacob, "Governor, what shall I do for you when I get out?" Jacob allegedly answered, "Talk about us like hell. We've abused you. You had no business here."

Why would Jacob ask Fairbank to tell the world about how bad Kentucky had been to him? Why would someone in such an important position want his own state to look bad? I am befuddled. If anyone has some more information or ideas to help me clear this up in my head, I would be glad to read them.

Image courtesy of the Kentucky Historical Society

The man I refer to is Richard Taylor Jacob (see my March 26, 2011 post). Jacob was the running mate Lt. Governor in 1863 when Thomas Bramlette was elected as Kentucky's chief executive. Before that he was colonel of the 9th Kentucky Cavalry (USA), although the pictured recruiting poster shows his attempt to raise an infantry regiment - yet another question I would like to answer. During the first years of the war Jacob and the 9th patrolled the state and chased John Hunt Morgan's raiders. Previous to the Civil War Jacob served with his brother-in-law by marriage and first Republican presidential candidate (1856) John C. Fremont in California. Jacob's marriage to Sarah Benton, daughter of powerful Missouri senator Thomas Hart Benton, only added to his family connections. He was also related to Zachary Taylor and his sister married a son of the "Great Compromiser" Henry Clay.

So, back to the question at hand: why would a strict conservative, opposed to emancipation and black soldiers, go out of his way to pardon Calvin Fairbank a known abolitionist and slave thief?

To provide you with some more information, I will rely heavily on Fairbank's memoir, Rev. Calvin Fairbank during Slavery Times: How He Fought the Good Fight to Prepare the Way, published in 1890. In the book Fairbank states that when Bramlette and Jacob were elected, "That was my daylight! I well knew that they would be elected, and the first time Bramlette was called away (and that would probably be soon), Jacob would pardon me as lieutenant and acting governor of the state." Fairbank claims that Jacob was "a good friend to me, and believed my conviction illegal." Why would Jacob think Fairbank was convicted illegally?

Fairbank's first offense was when he and Delia Webster helped Lewis Hayden and family escape from Lexington in 1844. For his efforts he received a 15 year sentence that was reduced to five years and was released in 1849. He was caught again when he tried to help a female Louisville slave escape to Indiana in 1851. For this second offense he received another 15 year sentence. He languished in the Kentucky State Penitentiary in Frankfort, where he was often abused for his abolitionist sentiments, until Jacob's pardon in 1863.

Fairbank doesn't go into much detail about what prompted Jacob to pardon him. He stated, "Richard T. Jacob, Lieutenant Governor, had been committed to my favor for years: he had said to me before the war: 'If I was Governor, I would turn you out today.' He was the son of John I. Jacob of Louisville and the son-in-law of Thomas H. Benton of Missouri. So that he was related to, and inherited good blood." O.K., that relationship and blood stuff is all well and good, but I want to know why Jacob was "committed to" Fairbank's "favor." He continued in his memoir that people had been pleading on his behalf to be released, including General James Harlan. Did he mean John Marshall Harlan, who was a colonel in the Civil War, or did he mean James Harlan, John's father, who I don't think was ever in a military role. Anyway, Fairbank continued, "I was anxious for Bramlette's absence for a while, that Jacob might hold the helm for a few hours; for Bramlette refused to interfere. I knew Jacob would." How did he know Jacob would, other than what Jacob had possibly told him before the war?

Fairbank's next sentence is especially confusing considering Jacob's expressed racist leanings. "The time had at last arrived when the people and government could see distinctly that it was the Africo-American's war: - that as he went, we went; as we went, he went:- we must both go together." This doesn't sound at all like the Jacob that railed against Lincoln, the Emancipation Proclamation and black soldiers. "President Lincoln had sent General [Speed] Fry to Kentucky with orders to enroll all the African people:-slave, free - male, female, - old, young; and the men competent for military service separately. Governor Bramlette forbade it. Fry reported to the President. Then was opened a discussion over the wires for several days. I watched this as my forlorn hope." Bramlette was ordered to Washington to speak to Lincoln and Fairbank got his fondest wish. Jacob came to the prison and said to the abolitionist, "How are you Fairbank? Well, I'm going to turn you out. Sneed, get up a little petition to knock the blows off me. I'm going to turn him out anyway." Fairbank asked Jacob, "Governor, what shall I do for you when I get out?" Jacob allegedly answered, "Talk about us like hell. We've abused you. You had no business here."

Why would Jacob ask Fairbank to tell the world about how bad Kentucky had been to him? Why would someone in such an important position want his own state to look bad? I am befuddled. If anyone has some more information or ideas to help me clear this up in my head, I would be glad to read them.

Image courtesy of the Kentucky Historical Society

Saturday, May 12, 2012

Just Finished Reading

Half Slave and Half Free: The Roots of Civil War, ( published in 1992) is another book that had slid under my radar for too long. I happened to pick up this copy in a small Charleston, South Carolina bookstore about a year ago. I came to the conclusion a long time ago that there are just simply too many good books and too little time to read them. I'm looking forward to retirement some day so I can make a valiant attempt to catch up.

This book was not quite what I was expecting - at least the first half wasn't. I suppose I was expecting a David M. Potter-esque, The Impending Crisis, 1848-1861, but much of it wasn't like that at all.

In order to attempt to understand and thus explain how the coming of the Civil War happened, Levine looks relatively closely at the social systems - free and slave - of America's two sections of the nineteenth century and the culture and politics each spawned. Levine argues rather persuasively that "the distinctive ways in which North and South organized their labor systems left their mark on all aspects of regional life - including family, gender, leisure patterns and both religious and secular ideologies. Such cultural changes, in turn, deeply influenced political life." Of course it was those politics that brought about secession and war.

The first four chapters go back and forth between the South and the and North showing those social and cultural peculiarities of each section from the post-Revolution era to the late antebellum period. I especially enjoyed these chapters, as Levine puts forth a clear and well argued analysis.

The last six chapters of the book are toward what I was expecting - more like The Impending Crisis. In these chapters Levine tells they story of how from the beginning of the nineteenth century to the Civil War, the "slave question" and the nation's struggle with it eventually brought on conflict between North and South.

If you are looking for a book, that in 240 pages of text, covers how this nation came to blows and that brought about the tragedy of over 620,000 deaths, in a scholarly, well researched, but highly readable book, then Half Slave and Half Free is probably for you. On a scale of 1 to 5 I give it a 4.75.

This book was not quite what I was expecting - at least the first half wasn't. I suppose I was expecting a David M. Potter-esque, The Impending Crisis, 1848-1861, but much of it wasn't like that at all.

In order to attempt to understand and thus explain how the coming of the Civil War happened, Levine looks relatively closely at the social systems - free and slave - of America's two sections of the nineteenth century and the culture and politics each spawned. Levine argues rather persuasively that "the distinctive ways in which North and South organized their labor systems left their mark on all aspects of regional life - including family, gender, leisure patterns and both religious and secular ideologies. Such cultural changes, in turn, deeply influenced political life." Of course it was those politics that brought about secession and war.

The first four chapters go back and forth between the South and the and North showing those social and cultural peculiarities of each section from the post-Revolution era to the late antebellum period. I especially enjoyed these chapters, as Levine puts forth a clear and well argued analysis.

The last six chapters of the book are toward what I was expecting - more like The Impending Crisis. In these chapters Levine tells they story of how from the beginning of the nineteenth century to the Civil War, the "slave question" and the nation's struggle with it eventually brought on conflict between North and South.

If you are looking for a book, that in 240 pages of text, covers how this nation came to blows and that brought about the tragedy of over 620,000 deaths, in a scholarly, well researched, but highly readable book, then Half Slave and Half Free is probably for you. On a scale of 1 to 5 I give it a 4.75.

Thursday, May 10, 2012

A Visit to Ball's Bluff Battlefield

This past weekend I had the pleasure of visiting northern Virginia. I was in the Old Dominion to see part of the Virginia Historical Society's traveling exhibit, "An American Turning Point: The Civil War in Virginia," which was on display at the Museum of the Shenandoah Valley in Winchester. The exhibit was fantastic. It combined a traditional exhibit with artifacts and labels with some cutting edge and thought provoking interactive stations. I highly recommend a viewing if you get the chance.

I also had the pleasure of stopping in Leesburg to visit the Ball's Bluff Battlefield. I had passed near the battlefield on Highway 15 a number of times over the years, but had not taken the time to see what is there.

When Federal troops under the command of Gen. Charles Stone tried to cross the Potomac River at this point on October 21, 1861, a sharp fight ensued and the Yankees were badly repulsed by Confederates under General Nathan "Shanks" Evans.

During the panicked retreat the Federals were driven down the extremely steep slope that led to the Potomac River.

Boats that attempted to ferry the Union soldiers back to the Maryland side of the river capsized and soldiers ran directly into the water attempting to avoid capture. Many drowned and made easy targets for the Confederates in pursuit.

A number of the Union soldiers killed in the fight washed up along the Potomac River as far down stream as Washington, D.C.

One of the most noticeable features of the battlefield today is the tiny National Cemetery. It is the resting place of 54 soldiers killed at the battle. The total casualties for the Union was 223 killed, 226 wounded and 553 captured. The Confederates only suffered about 150 casualties in the lopsided engagement.

Of the Union casualties, the most significant was Senator Edward Baker of Pennsylvania. Baker, colonel of the 71st Pennsylvania Infantry has the distinction to be the only U.S. Senator in history killed in battle. He was mortally wounded at about 4:30 p.m. that day.

This Union patriotic envelope mourns the death of Senator Baker.

Ball's Bluff, while being a minor engagement compared to later battles, did have serious political repercussions. Due to the death of Senator Baker and the uneven number of casualties, Congress formed the Congressional Joint Committee on the War, which investigated army actions and caused commanders to perhaps be more cautious than they would have been otherwise.

For more on the Battle of Ball's Bluff check out the Civil War Trust's page on this engagement:

http://www.civilwar.org/battlefields/ballsbluff.html

Non-photographic images courtesy of Library of Congress

Wednesday, May 9, 2012

And Another Envelope

Another Confederate patriotic envelope called on their Revolutionary War heritage and advised their Union enemies not to "TREAD ON US." During the American Revolution, the rattlesnake, was a symbol of the colonies. To the English it was derogatory, as they thought snakes symbolized sneaky shiftiness and potential treachery. To the Americans the rattlesnake was something to be glorified. To them it showed that if left alone there would be not trouble, but if bothered it would give warning and then strike. The rattlesnake on the envelope is coiled around the national symbol of the new country, their flag.

Below the rattlesnake and flags motif is the phrase "EVER READY WITH OUR LIVES AND FORTUNES," and an image of a palmetto tree; presumably referencing the state of South Carolina.

Courtesy Library of Congress

Tuesday, May 8, 2012

Another Envelope

As one might imagine the South had their own take on patriotic envelopes in the Civil War. Just like the Union, the people of Confederacy often used these pieces of ephemera to boost pride in their cause and show where they stood on the sectional issues.

This particular one shows an infant - probably meant to represent the new born nation - sitting on a globe, marking his place in the world. He is holding an eleven-star first national Confederate flag in his right hand while choking a snake labeled "ABOLITION" with his left hand.

Obviously, the artist who created this envelope image wanted to make a point as clear Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens' "Cornerstone Speech" given on March 21, 1861 in Savannah, Georgia. In the speech Stephens exclaimed, "The constitution, it is true, secured every essential guarantee to the institution [slavery] while it should last, and hence no argument can be justly urged against the constitutional guarantees thus secured, because of the common sentiment of the day. Those ideas, however, were fundamentally wrong. They rested upon the assumption of the equality of the races. This was an error. It was a sandy foundation, and the government [United States] built upon it fell when the 'storm came and the wind blew.' Our new government [the Confederacy] is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not the equal to the white man; that slavery, subordination to the superior race, is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical and moral truth." In a political society and economic system built on slavery, there is no room for discussion about its end; thus the symbolism of South's strangle of the evil snake of abolition.

Courtesy Library of Congress

Monday, May 7, 2012

Just Finished Reading

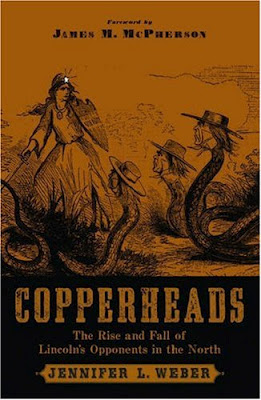

About a year or so ago I saw an episode of History Detectives on PBS where they were trying to find out some information on a walking cane that had a coiled copperhead snake handle. They were able to confirm that it belonged to a vehement Copperhead politician named Henry Clay Dean from Iowa. They even found a reference to the cane in a newspaper article. Naturally, I have often read about Copperheads in general Civil War history books, but I had not read a thorough account of them until I read Jennifer Weber's Copperheads: The Rise and Fall of Lincoln's Opponents in the North.

If you're not familiar with the Copperhead movement during the Civil War, they were basically conservative anti-war Democrats that wished to have (as a slogan some used) "the Constitution as it is, the Union as it was," which meant they believed in a strict interpretation of the Constitution and a compromise on the slavery issue. The name "Copperhead" came from some members who wore a penny on their lapel to designate themselves. Some of these Peace Democrats also went by the name "Butternuts," especially those in the lower Midwest. The Copperheads were vehemently opposed to infringements of civil liberties, despised a powerful federal government, defended states' rights and thought emancipation was a dangerous and ill-advised idea. In an era where most whites displayed racist tendencies, the Copperheads were especially so.

Weber's book contends that the Copperhead movement developed in three phases. The first was with secession and what they thought was Lincoln's overstep of his constitutional powers. The second phase was with the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation and then the draft. The final phase was in the summer of 1864 with the large loss of life the Union army experienced as it tried to destroy the Confederate armies and which was not well received in the North.

Copperheads explores a number of the leading men, most from the Midwest, that led the movement. Chief among these was Ohio congressman Clement Vallandigham. Vallandigham's vehement outbursts in print and in speech were not appreciated by the Lincoln administration. The Ohioan was promptly arrested and sent across the lines into Confederate territory in Tennessee in 1863. He made his way to Richmond then the Caribbean and finally to Canada where she stayed much of the rest of the war and ran for governor of Ohio in exile. He lost.

One aspect of the book I found quite intriguing was the author's look at how Union soldiers perceived the Copperheads. Being that the Copperheads opposed the war effort one can image what the soldiers out doing the fighting and dying thought about them. Weber shows with a number of primary source letters how Union soldiers wished they could get their hands on those that fought against the war effort from behind their own lines and on the home front. The soldiers showed their support for the war and disdain for the Copperheads and the Peace Democrats by voting overwhelmingly for Lincoln in the fall of 1864. Most Northern soldiers believed their sacrifices would be in vain if they did not see the war to its conclusion.

Weber too points out wisely that the Copperheads never really offered any substantial alternatives to Lincoln's policies. They only attempted to harangue and obstruct the administration that understood too much sacrifice had been made to compromise with the South on reunification and emancipation. The Copperheads also seemingly ignored the South's constant refusal to consider a peace without their independence and slavery firmly secured.

I do wish that Weber would have provided more coverage about how the Copperheads hurt the Democratic party's chances for regaining political power in the post Civil War years. The political clout of former soldier organizations such as the Grand Army of the Republic and their Republican Party connections surely must have severely damaged the Democratic party - even those Democrats that supported the Union war effort - for years.

Copperheads was very informative and well written. I think it is important to understand the potential power the Peace Democrats had, especially in certain regions, and how they could have altered events significantly if it had not been for the Union army successes in the late summer and early fall of 1864. On a scale of 1 to 5, I give Copperheads a 4.5.

If you're not familiar with the Copperhead movement during the Civil War, they were basically conservative anti-war Democrats that wished to have (as a slogan some used) "the Constitution as it is, the Union as it was," which meant they believed in a strict interpretation of the Constitution and a compromise on the slavery issue. The name "Copperhead" came from some members who wore a penny on their lapel to designate themselves. Some of these Peace Democrats also went by the name "Butternuts," especially those in the lower Midwest. The Copperheads were vehemently opposed to infringements of civil liberties, despised a powerful federal government, defended states' rights and thought emancipation was a dangerous and ill-advised idea. In an era where most whites displayed racist tendencies, the Copperheads were especially so.

Weber's book contends that the Copperhead movement developed in three phases. The first was with secession and what they thought was Lincoln's overstep of his constitutional powers. The second phase was with the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation and then the draft. The final phase was in the summer of 1864 with the large loss of life the Union army experienced as it tried to destroy the Confederate armies and which was not well received in the North.

Copperheads explores a number of the leading men, most from the Midwest, that led the movement. Chief among these was Ohio congressman Clement Vallandigham. Vallandigham's vehement outbursts in print and in speech were not appreciated by the Lincoln administration. The Ohioan was promptly arrested and sent across the lines into Confederate territory in Tennessee in 1863. He made his way to Richmond then the Caribbean and finally to Canada where she stayed much of the rest of the war and ran for governor of Ohio in exile. He lost.

One aspect of the book I found quite intriguing was the author's look at how Union soldiers perceived the Copperheads. Being that the Copperheads opposed the war effort one can image what the soldiers out doing the fighting and dying thought about them. Weber shows with a number of primary source letters how Union soldiers wished they could get their hands on those that fought against the war effort from behind their own lines and on the home front. The soldiers showed their support for the war and disdain for the Copperheads and the Peace Democrats by voting overwhelmingly for Lincoln in the fall of 1864. Most Northern soldiers believed their sacrifices would be in vain if they did not see the war to its conclusion.

Weber too points out wisely that the Copperheads never really offered any substantial alternatives to Lincoln's policies. They only attempted to harangue and obstruct the administration that understood too much sacrifice had been made to compromise with the South on reunification and emancipation. The Copperheads also seemingly ignored the South's constant refusal to consider a peace without their independence and slavery firmly secured.

I do wish that Weber would have provided more coverage about how the Copperheads hurt the Democratic party's chances for regaining political power in the post Civil War years. The political clout of former soldier organizations such as the Grand Army of the Republic and their Republican Party connections surely must have severely damaged the Democratic party - even those Democrats that supported the Union war effort - for years.

Copperheads was very informative and well written. I think it is important to understand the potential power the Peace Democrats had, especially in certain regions, and how they could have altered events significantly if it had not been for the Union army successes in the late summer and early fall of 1864. On a scale of 1 to 5, I give Copperheads a 4.5.

Thursday, May 3, 2012

A Different Kind of Secession

On the Library of Congress website there are a number of examples of Civil War era envelopes. These rare pieces of ephemera provide a unique perspective on this contentious time period in that they show diverse examples of expressions of patriotism. Many of them are satirical, such as the one above, which shows a slave woman and her boy child "seceding" from their life in bondage by running away.

Courtesy Library of Congress

Wednesday, May 2, 2012

Just Finished Reading

If one can have or should have a favorite Civil War battle to study, mine is the Battle of Franklin, Tennessee. I am not sure exactly what captivates me about this engagement. I suppose it is partly the sheer bravery of the Confederates, charging in numbers much larger than Pickett's more famous attack at Gettysburg, and I guess it is partly the Union army's stealth to get by their foe at Spring Hill and then impede the Southerners in their drive toward their Nashville target.

Maybe it is also the tragedy of the battle and its tragic personalities; the one armed, one legged General John Bell Hood, Irish immigrant and officer extraordinaire Patrick R. Cleburne, Captain Tod Carter, who died yards from his home, the Carter House, which was caught in the eye of the storm on November 30, 1864. And then too there is the damage, much of it still visible on the grounds of the Carter House to this day.

After Atlanta fell to Sherman's forces, Confederate general John Bell Hood had to decide what to do next. He finally decided that instead of trying to further block Sherman and the Union army wherever they were going to go, he would instead head north and try to reclaim Tennessee, and if all went according to plan there, well, why not go on up into the Bluegrass state too. Years after the failed Tennessee campaign Hood explained his reasoning. "I was imbued with the belief that I could accomplish this feat [destroy Union army and capture Nashville], afterward march northeast, pass the Cumberland river at some crossing where the gunboats, if too formidable at other points, were unable to interfere; then move into Kentucky, and take position with our left at or near Richmond...In this position I could threaten Cincinnati, and recruit the Army from Kentucky and Tennessee; the former State was reported at this juncture, to be more aroused and embittered against the Federals than at any period of the war." Hood was correct, Kentucky was "aroused and embittered against the Federals," due largely to Lincoln's earlier Emancipation Proclamation, the Union army's enlisting of slaves and the hard-handed tactics used against those of suspect loyalty, but Kentuckians were not likely to join what seemed to be a doomed government, what with Atlanta captured and Lee backed up to Richmond and Petersburg.

The author, Eric Jacobson, gives the Spring Hill Affair about the best treatment I have read. Jacobson claims that there was plenty of blame to go around on the Confederate side for letting John Schofield's Union army slip by at Spring Hill, but that ultimately the blame rests with the army's commander, Hood. I agree, however, it seems to me in certain situations, division and brigade commanders have to take initiative and show some common sense and tactical skill. I personally think Major General John Calvin Brown is probably as guilty as anyone. Whoever was at fault, the Confederate's missed a grand opportunity to destroy the Union army that virtually destroyed them the following day.

One thing I really liked about the book was Jacobson's use of mini-biographies when introducing the reader to the major players in these events. It really reminded me of Peter Cozzens' many works on the Western Theater. I think these little background looks helps the reader better understand the personality of the individual being examined.

There were few battles that were as brutal as Franklin. Although it did not have the highest casualty rate in the Civil War, for the short time the battle actually lasted, there was not one more fiercely contested. For whatever reason - possibly due to disgust at letting the enemy slip by the night before - Hood chose a direct frontal attack on the entrenched Union army at Franklin rather than attempt to flank them or go around them and find better ground for a fight. And on the gray lines came and down they went in rows. The slaughter was terrible. A conservative figure for Confederate casualties is given at 5,800. The Union army, with the benefit of fortifications, lost 189 killed, 1033 wounded and 1,104 captured or missing. The loss to the Confederate officer corps was astounding. Five Southern generals were killed outright: Patrick Cleburne, John Adams, States Rights Gist, Otho Stahl, and Hiram Granbury. General John C. Carter was mortally wounded in the battle and died a few days later. A total of 68 Confederate field officers were casualties!

Amazingly after the terrible destruction at Franklin, Hood followed the retreating Schofield on to Nashville and where he was attacked by George Thomas's strengthened federal army on December 15-16. Hood was again soundly defeated, retreated out of Tennessee and resigned his position.

I found For Cause and Country to be a good read. A number of typographical errors throughout the book, most dealing with tense or sentence agreement, detracted somewhat, but overall it was a solid piece of history. On a scale of 1 to 5, I give it a 4.25.

Maybe it is also the tragedy of the battle and its tragic personalities; the one armed, one legged General John Bell Hood, Irish immigrant and officer extraordinaire Patrick R. Cleburne, Captain Tod Carter, who died yards from his home, the Carter House, which was caught in the eye of the storm on November 30, 1864. And then too there is the damage, much of it still visible on the grounds of the Carter House to this day.

After Atlanta fell to Sherman's forces, Confederate general John Bell Hood had to decide what to do next. He finally decided that instead of trying to further block Sherman and the Union army wherever they were going to go, he would instead head north and try to reclaim Tennessee, and if all went according to plan there, well, why not go on up into the Bluegrass state too. Years after the failed Tennessee campaign Hood explained his reasoning. "I was imbued with the belief that I could accomplish this feat [destroy Union army and capture Nashville], afterward march northeast, pass the Cumberland river at some crossing where the gunboats, if too formidable at other points, were unable to interfere; then move into Kentucky, and take position with our left at or near Richmond...In this position I could threaten Cincinnati, and recruit the Army from Kentucky and Tennessee; the former State was reported at this juncture, to be more aroused and embittered against the Federals than at any period of the war." Hood was correct, Kentucky was "aroused and embittered against the Federals," due largely to Lincoln's earlier Emancipation Proclamation, the Union army's enlisting of slaves and the hard-handed tactics used against those of suspect loyalty, but Kentuckians were not likely to join what seemed to be a doomed government, what with Atlanta captured and Lee backed up to Richmond and Petersburg.

The author, Eric Jacobson, gives the Spring Hill Affair about the best treatment I have read. Jacobson claims that there was plenty of blame to go around on the Confederate side for letting John Schofield's Union army slip by at Spring Hill, but that ultimately the blame rests with the army's commander, Hood. I agree, however, it seems to me in certain situations, division and brigade commanders have to take initiative and show some common sense and tactical skill. I personally think Major General John Calvin Brown is probably as guilty as anyone. Whoever was at fault, the Confederate's missed a grand opportunity to destroy the Union army that virtually destroyed them the following day.

One thing I really liked about the book was Jacobson's use of mini-biographies when introducing the reader to the major players in these events. It really reminded me of Peter Cozzens' many works on the Western Theater. I think these little background looks helps the reader better understand the personality of the individual being examined.

There were few battles that were as brutal as Franklin. Although it did not have the highest casualty rate in the Civil War, for the short time the battle actually lasted, there was not one more fiercely contested. For whatever reason - possibly due to disgust at letting the enemy slip by the night before - Hood chose a direct frontal attack on the entrenched Union army at Franklin rather than attempt to flank them or go around them and find better ground for a fight. And on the gray lines came and down they went in rows. The slaughter was terrible. A conservative figure for Confederate casualties is given at 5,800. The Union army, with the benefit of fortifications, lost 189 killed, 1033 wounded and 1,104 captured or missing. The loss to the Confederate officer corps was astounding. Five Southern generals were killed outright: Patrick Cleburne, John Adams, States Rights Gist, Otho Stahl, and Hiram Granbury. General John C. Carter was mortally wounded in the battle and died a few days later. A total of 68 Confederate field officers were casualties!

Amazingly after the terrible destruction at Franklin, Hood followed the retreating Schofield on to Nashville and where he was attacked by George Thomas's strengthened federal army on December 15-16. Hood was again soundly defeated, retreated out of Tennessee and resigned his position.