In some respects 2021 proved to be more challenging than 2020. While many of COVID-19's safety restrictions eased as cases reduced, demands at work increased. The summer and fall months were particularly busy. All of this goes to say that the time I normally devote to reading and the mental energy it takes to comprehend and process those books was just not on par with past the past several years. Similarly, the number of posts on this blog dropped to one of its lowest totals over its almost 13 year existence.

However, this year also brought a number of wonderful learning opportunities that helped me grow and network in the history field. I suppose I should be thankful for what all I've been able to accomplish this year rather than compare it to those of the past, but, that's probably just the historian in me.

Anyway, this year I was able to complete 48 books; just less than one a week. As I've done in the past, I've highlighted those that I particularly enjoyed or found especially insightful. In addition, this year, I've separated them by the month that I completed them.

January

1. Not Even Past: The Stories We Keep Telling about the Civil War by Cody Marrs

2. The Big House after Slavery: Virginia Plantation Families and Their Postbellum Domestic Experiment by Amy Feely Morsman

3. Living By Inches: The Smells, Sounds, Tastes, and Feeling of Captivity in Civil War Prisons by Evan A. Kutzler

4. Family Bonds: Free Blacks and Re-enslavement in Antebellum Virginia by Ted Maris-Wolf

5. We Have it Damn Hard Out Here: The Civil War Letters of Sgt. Thomas W. Smith, 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry by Eric J. Wittenburg

6. We Need Men: The Union Draft in the Civil War by James W. Geary

7. Remaking the Republic: Black Politics and the Creation of American Citizenship by Christopher James Bonner

February

8. Voices from the Attic: The Williamstown Boys in the Civil War by Carleton Young

9. A Thousand May Fall: Life, Death, and Survival in the Union Army by Brian Matthew Jordan

10. Carrying the Colors: The Life and Legacy of Medal of Honor Recipient Andrew Jackson Smith by W. Robert Beckman and Sharon S. MacDonald

11. The Black Civil War Soldier: A Visual History of of Conflict and Citizenship by Deborah Willis

12. Lone Star Confederate: A Gallant and Good Soldier of the Fifth Texas Infantry edited by George Skoch and Mark W. Perkins

March

13. Defend the Valley: A Shenandoah Family in the Civil War by Margaretta Barton Colt

14. Kate: The Journal of a Confederate Nurse by Kate Cumming, edited by Richard Barksdale Harwell

15. Clara Barton's Civil War: Between Bullet and Hospital by Donald C. Pfanz

April

16. The Howling Storm: Weather, Climate, and the American Civil War by Kenneth W. Noe

17. Confederate Exceptionalism: Civil War Myth and Memory in the 21st Century by Nicole Maurantonio

18. Embattled Freedom: Chronicle of a Fugitive-Slave Haven in the Wary North by Jim Remsen

May

19. Slavery and the Underground Railroad in South Central Pennsylvania by Cooper C. Wingert

20. Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation: The End of Slavery in America by Allen C. Guelzo

21. Slavery and Freedom in the Shenandoah Valley during the Civil War by Jonathan A. Noyalas

June

22. The Women's Fight: The Civil War's Battles for Home, Freedom, and Nation by Thavolia Glymph

23. The Colors of Dignity: Memoirs of Civil War Brigadier General Giles Waldo Shurtleff edited by Catherine Durant Voorhees

24. Thaddeus Stevens: Civil War Revolutionary, Fighter for Racial Justice by Bruce Levine

25. Seizing Destiny: The Army of the Potomac's "Valley Forge" and the Civil War Winter that Saved the Union by Albert Z. Conner with Chris Mackowski

July

26. How the Word is Spread: Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America by Clint Smith

27. Jubal Early's Raid on Washington by Benjamin Franklin Cooling

28. The Ledger and the Chain: How Domestic Traders Shaped America by Joshua D. Rothman

29. This Infernal War: The Civil War Letters of William and Jane Standard edited by Timothy Mason Roberts

30. A Holy Baptism of Fire and Blood: The Bible and the American Civil War by James P. Beard

31. Destroy the Junction: The Wilson-Kautz Raid and the Battle for Staunton River Bridge by Greg Eanes

August

32. Lincoln's Mercenaries: Economic Motivation among Union Soldiers during the Civil War by William Marvel

33. Force and Freedom: Black Abolitionists and the Politics of Violence by Kellie Carter Jackson

34. The Battle of Glendale: Robert E. Lee's Lost Opportunity by Douglas Crenshaw

35. Topsy-Turvy: How the Civil War Turned the World Upside for Southern Children by Anna Jabour

September

36. Sheridan's James River Campaign through Central Virginia by Richard L. Nicholas

37. His Truth Is Marching On: John Lewis and the Power of Hope by Jon Meacham

38. War's Relentless Hand: Twelve Tales of Civil War Soldiers by Mark Dunkleman

39. Decisions of the Seven Days: The Sixteen Critical Decisions that Defined the Battles by Matt Spruill

October

40. Claiming Union Widowhood: Race, Respectability, and Poverty in the Post-emancipation South by Brandi Clay Brimmer

41. An Intimate Economy: Enslaved Women, Work, and the Domestic Slave Trade by Alexandra J. Finley

November

42. The Great Battle Never Fought: The Mine Run Campaign by Chris Mackowski

43. No Excuses: The Making of a Head Coach by Bob Stoops

44. Grant's Left Hook: The Bermuda Hundred Campaign by Sean Michael Chick

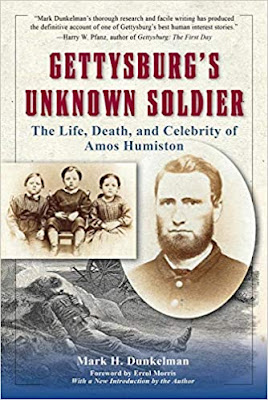

45. Gettysburg's Unknown Soldier: The Life Death, and Celebrity of Amos Humiston by Mark Dunkleman

46. Aberration of Mind: Suicide and Suffering in the Civil War-Era South by Diane Miller Sommerville

December

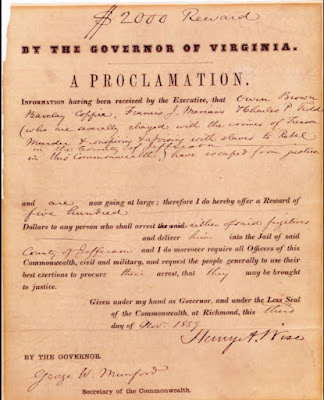

47. America's Good Terrorist: John Brown and the Harpers Ferry Raid by Charles P. Roland, Jr.

48. Ties that Bind: The Story of an Afro-Cherokee Family in Slavery and Freedom by Tiya Miles