|

| Photo courtesy of Wisteria Perry |

“Penetrating gunshot wound, ball entered

three inches below right axilla, passed through thorax, lung perforated . . . .“

So reads the Surgeon General’s copied records in the 1869 widow’s pension

case filed by Sarah Cotton, who was seeking to provide evidence to receive

financial compensation for her soldier husband’s death over four years earlier.

Although not enslaved, the circumstances that brought Sarah Cotton to this

point in her life developed in large part due to the institution of slavery. A

little bit of backstory will help to develop that connection further, although admittedly,

many holes remain due to the lack of records.

When Pompey Cotton was born in Martin County, North Carolina, about 1840, the United States population included almost 2,500,000 enslaved men, women, and children and over 385,000 free people of color. Pompey Cotton was enslaved, and Sarah, then Smith, was a free woman of color. It is unknown how Pompey came to live in Virginia, but perhaps a former enslaver sold him. It is also unknown how Pompey and Sarah met and then fell in love, but records show that they apparently married at Deep Creek, Norfolk County, Virginia. The location was perhaps where Pompey worked at the time. It is possible that Pompey was leased out, as one of Sarah’s records states on their wedding day that Pompey went to pay his “quarter’s wages” to his enslaver Edwin Ives, so he was apparently not living on Ives’ Princess Anne County, Virginia plantation.

There is conflicting testimony in the Sarah’s widow’s pension file on when the marriage occurred. Deposed in July 1869, Miles Butt (a Company D, comrade of Cotton’s) and Timothy Moreley, agreed with Sarah Cotton that the wedding occurred on October 25, 1860, and that there was not a formal ceremony but there was a “supper and dance given at the time.” In August 1869, Benjamin Anderson and George Floyd provided testimony that the wedding happened “between new and old Christmas” [December 25, 1860 and January 5, 1861].

Regardless of the circumstances of the apparent marriage, Pompey’s enslaver, Edwin Ives, does appear in the historical record. In the 1860 census he appears as a 37-year-old Princess Anne County farmer living with this wife, Mary, and two free men of color (perhaps brothers), Hillary and Emerson Cuffee, who must have worked for Ives. At the time of the census Ives possessed $16,000 in real estate, and $8,360 in personal property, which included 14 enslaved individuals, who ranged in age from 80 to three. Among the enumerated enslaved are two 21 year old men, both of whom closely match Pompey Cotton’s age in 1860.

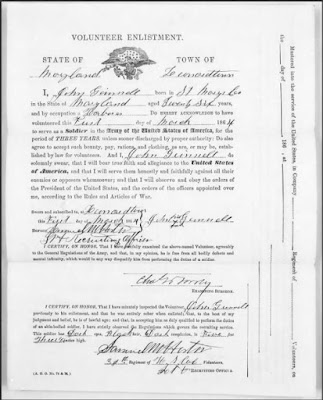

Witnesses in Sarah Cotton’s pension claim stated that she and Pompey “lived together in the same domicile and were regarded as husband and wife by their owner friends and neighbors until Pompey enlisted.” Cotton joined Company D, 38th United States Colored Infantry (USCI) on February 10, 1864, and formally mustered into service on February 23. Standing six feet, two inches tall, Cotton likely towered over most of his comrades. The enrolling officer noted that Cotton had a “dark” complexion. Perhaps Pompey’s intelligence, personality, or impressive height influenced his officers to assign him the rank of corporal on the day he enlisted.

Whether Sarah came with Pompey to the Norfolk area is unknown. As historian James Bryant notes, “the families of former slaves serving in the Union army not only suffered financially [due to initially receiving less pay than White soldiers], but were closer to battle fronts in Union-occupied areas of the South. Southern black families often suffered from abuse by white civilians as well as unsympathetic Union military officials.” Some Black soldiers’ wives actually braved the dangers of army life and followed their soldier husbands to the front doing camp duties. Lt. John H. Owen, a White officer in the 36th USCI, which eventually served in the same brigade as Corp. Cotton’s 38th USCI, wrote home explaining, “here are two women wives of men in the Regt. that have necessitated in following us—through shot and shell . . . They do not seem to be afraid—one is our cook.” Other soldiers’ wives earned much needed funds as company laundresses.

Commanded by Lt. Col. Dexter E. Clapp, the 38th USCI joined the Eighteen Corps, Army of the James, in June 1864, and moved to the nearest scene of action at Petersburg. That month Cotton made “color corporal.” For Capt. Peter Schlick’s Company D, and the rest of the 38th USCI, serving in the trenches at Petersburg throughout the summer proved quite dangerous. Thomas Morris Chester, a Black correspondent for the Philadelphia Press, wrote, “There is not a day but what some brave black defender of the Union is made to bite the dust by at rebel sharpshooter or picket. . . .” But Chester also noted, “They are ever on the alert to catch a glimpse of a rebel, to whom they send their compliments by means of a leaden messenger. Between the negroes and the enemy it is war to the death. The colored troops have cheerfully accepted the conditions of the Confederate Government, that between them no quarter is to be shown.”

|

| Thomas Morris Chester |

In September 1864, while some of the soldiers in the Third Division of the Eighteenth Corps labored on the Dutch Gap canal project, others moved to Deep Bottom landing on the north side of the James River to man the bridgehead defenses and to serve picket duty. Yet others served at some of the forts down river on the James. However, at the end of the month, other than the 10th USCI, the division’s regiments consolidated at Deep Bottom for a planned assault. While the White divisions of the Eighteenth Corps attacked at Fort Harrison about three miles to the west, the Black Third Division was ordered to assault the Confederate defenses along New Market Road. The Tenth Corps was to provide support for the Black division if needed.

Early on September 29, Col. Stephen Duncan’s Brigade (4th and 6th USCI) made a desperate and valiant attempt on the Confederate works. Some made it to the earthwork line, but the majority fell attempting to navigate the double row of abatis, losing half of their force killed, wounded or captured in the effort. Col. Alonzo Draper’s Brigade (5th, 36th, and Cotton’s 38th USCI) attacked next, after Duncan’s Brigade, or what was left of it, fell back to reorganize. But instead of advancing in lines of battle as Duncan’s Brigade had attacked, Draper’s Brigade went forward in column. Enduring heavy casualties also, the second assault ground to a halt, but through a spirited cheer, and led largely by the Black non-commissioned officers after many of the White officers went down, momentum picked back up and the attackers went over the works pushing out the famous Texas Brigade defenders. White officers from the 38th USCI who received recognition afterward were: Capt. Schlick, of Corp. Cotton’s Company D, and Lt. Samuel Bancroft, also of Company D, “for daring and endurance. Being shot through the hip at the swamp, he crawled forward on his hands and knees, waving his sword and cheering his men to follow.” In addition, Sgt. Maj. Weiss, a White non-commissioned officer, elicited comment “for courage, gallantry, and good conduct in the attack.” More notably, three of Cotton’s Black comrades also garnered mention and received Medals of Honor for their heroic actions: 1st Sgt. Edward Ratcliff, Company C; Pvt. William Barnes, Company C; and Sgt. James Harris, Company B.

|

| Capt. Peter Schlick, Co. D, 38th USCI, courtesy of the Huntington Library |

The cost of victory came at a high price. From their starting point hundreds of yards away, up to the defensive earthworks, hundreds of killed and wounded men from the five main attacking regiments covered the ground. Writhing in pain, Corp. Pompey Cotton was among the wounded. His regiment suffered 21 killed, 12 mortally wounded, and 75 who were wounded but survived. Fortunately, since the Federal force held the field, medical help transferred the wounded from the battlefield to boats a mile away at the James River. Records are not clear, but Corp. Cotton may have received initial treatment at the Point of Rocks hospital near Petersburg. However, perhaps when surgeons discovered the true severity of his wound, he ended up at Balfour Hospital in Portsmouth, Virginia.

If Corp. Cotton’s wound had been limited to the right axilla (shoulder/arm joint), it is likely that he would have recovered with little complication, but since the minie ball traveled into his chest instead of traveling straight through, it resulted in damage to his right lung. Recovery cases from lung wounds did occur during the Civil War, but it was more the exception than the rule. Unfortunately, Corp. Cotton was not an exception. Medical knowledge of the time dictated that there was little surgeons could do for internal organ injuries. Cotton died at Balfour on October 3, 1864. He received an interment at Hampton National Cemetery where he rests in peace today. Company D’s Lt. George Everett filled out Corp. Cotton’s final paper work which included the statement that Cotton had “served honestly and faithfully in the field. . . .” Corp. Cotton’s inventory of last effects only listed three things: one pair of trousers, one half of a shelter tent, and a haversack.

|

| Lt. George Everett, Co. D, 38th USCI, courtesy of the Library of Congress |

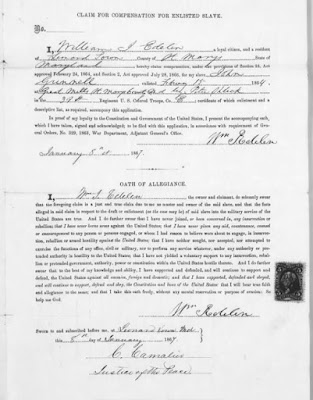

In an 1869 document in Sarah’s pension file she states that she did not learn about her husband’s death until six months later. However, an 1873 document appears to show that she lived with another man and that she went by Jane Mitchell after Cotton’s death. Her previous testimony said she had not remarried. Perhaps she viewed her relationship with John Mitchell, a sailor who served on a government steamer, and who died in 1867, as something other than a marriage. Regardless, Sarah’s pension payment of $8 per month stopped with this discovery by the Pension Bureau in 1873.

We remember Corp. Pompey Cotton, and honor his service and sacrifice. He enlisted and fought to abolish a labor system based on supposed inferiority. In doing so he helped change many people’s minds and became a respected non-commissioned officer in the United States army. Well done soldier!

.png)