Tomorrow marks the 154th anniversary of the famous Battle of the Crater. What must ultimately be determined a fiasco of an operation by the Union IX Corps could have had a greater chance of success had the attack's leadership not been almost totally absent and greater support provided.

Here black Union troops from Ferrero's Division mixed in deadly hand-to-hand combat with the Army of Northern Virginia's Confederate veterans for the first time. As most students of the battle know, the level of blood-lust was at a high at the Crater. Emotions overtook reason and self-control in this heated combat. Calls of "NO QUARTER!" and "REMEMBER FORT PILLOW!" by the attackers were answered with atrocities by the defenders.

The vitriol displayed by the Confederate soldiers, and the Southern press, is one that is difficult for the modern reader to fathom. When reading page 504 of Will Greene's recently published Volume 1 study of the Petersburg Campaign, A Campaign of Giants: From the Crossing of the James to the Crater, one is struck with the blatant tone of the editor of the Richmond Enquirer in the August 1-2, 1864 issue. "Let every salient we are called upon to defend be a Fort Pillow, and butcher every negro that Grant hurls against our brave troops, and permit them not to soil their hands with the capture of the negro." The paper then called for Gen. William Mahone, to not be so merciful in the future and to let the Southern soldiers carry out what he saw as a providential task. "We beg [Mahone] hereafter, when negroes are sent forward to murder the wounded and come shouting 'no quarter,' shut your eyes, General, strengthen your stomach with a little brandy and water, and let the work which God has entrusted to you and your brave men, go forward to its full completion; that is until every negro has been slaughtered."

Curious to see if these sentiments were similarly expressed in other papers, I looked up the Richmond Daily Dispatch of August 2, 1864. Although less explicit than the Enquirer, under the headline, THE WAR NEWS, it claimed unabashedly that the black troops were "slaughtered like sheep" and that "hundreds were slain."

The paper then mentioned that it was simply impossible for the Confederates to render aid to those wounded caught between the lines due to the Union sharpshooters. The writer also speculated on the length of the mine tunnel, guessing that it was 600 feet long, which was about 90 feet longer than the actual distance. It, too, gave the killed and wounded figures of Mahone's counterattacking force. The article continued with a deprecating tone about the black and white Union prisoners:

Fighting black Union troops on the battlefield and attempting to contain the enslaved on the shrinking home front was certainly disconcerting to white Southerners. Many of them must have wondered about the future and what would ultimately become of their new nation. Would it slip away along with each mile of lost ground or would a miracle occur to turn the tide? It would take hundreds of more lives and more than eight months to finally decide the outcome, and turn their worlds upside down.

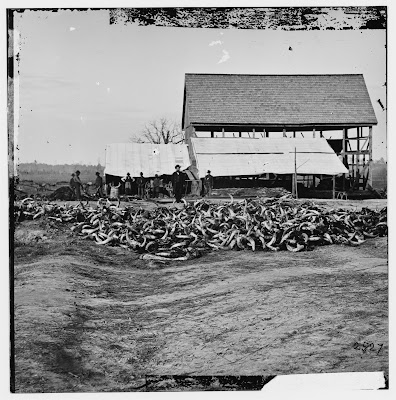

Image of "Mahone's Counterattack" courtesy of Don Troiani artworks.