The phrase has been used across the ages. In the Texas Revolution it was "Remember the Alamo." In the Spanish-American War it was "Remember the Maine." In World War I it was "Remember the Lusitania." In World War II it was "Remember Pearl Harbor." And, in our most recent conflicts, it is "Remember 9/11." These phrases helped both soldiers and civilians to remember notorious acts by enemies and inspired determination and action to avenge such wrongs.

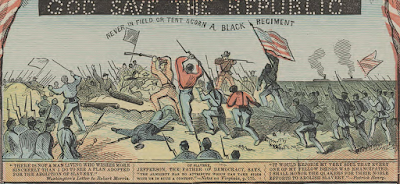

In the Civil War, for the United States Colored Troops, "Remember Fort Pillow" was the battle cry more than once or twice.

Fort Pillow, fought on April 12, 1864, on the Mississippi River in West Tennessee, involved a garrison of white Unionist Tennesseans and black troops, who were requested to surrender to forces under the command of Confederate cavalry general Nathan Bedford Forrest. Not being a patient man, Forrest allegedly used a truce period to move his men closer to the fort. When surrender was refused, Forrest's men stormed the position, overtaking the troops inside. In a congressional investigation held later about the action, it was reported that the Confederates refused to allow a large number of the black troops inside to surrender, maliciously killing the capitulating defenders.

The word spread rapidly about the atrocities at Fort Pillow. At the Battle of Resaca, Georgia, in May 1864, in the terrific fighting that occurred there, white Wisconsin soldiers overran a Confederate artillery position and happened upon a Confederate with "Fort Pillow" tattooed on his arm. Instead of taking him as a prisoner of war, the leaped upon him bayoneting and shooting him.

Fort Pillow's legacy was especially strong among the rapidly expanding USCT regiments in the spring and summer of 1864. Three and a half months after Fort Pillow, at the Battle of the Crater, black troops of the IX Corps yelled "Remember Fort Pillow," and "No quarter to the Rebels," in the fierce maelstrom that raged around them. However, at the Crater, the Confederates gained the upper hand in a fierce counter attack and reversed the cry of "No quarter" to many of the black troops, taking the phrase to heart and carrying out brutal acts against their black opponents.

To help motivate and encourage the African American soldiers of Gen. Charles J. Paine's division before the desperate fight at the Battle of New Market Heights, on September 29, 1864, Maj. Gen. Benjamin Franklin Butler (pictured above) implored the men to "Remember Fort Pillow!" In his memoirs, published in 1892, Butler claimed his words to them were:

"At half past four o'clock I found the colored division, rising three thousand men, occupying a plain which shelved toward the [James] river, so that they were not observed by the enemy . . . . They were formed in close column of division right in front. I rode through the division, addressed a few words of encouragement and confidence to the troops. I told them to go over and take a work which would be before them after they got over the hill, and that they must take it all hazards, and that when they went over the parapet into it their war cry should be 'Remember Fort Pillow!'"

As at the Battle of the Crater, the Confederates had an advantage. They were ensconced behind breastworks. The Southerners, after they shattered the attack by Col. Duncan's Brigade, consisting of the 4th and 5th USCI regiments, and just before the attack of Col. Draper's Brigade, comprised of the 5th, 36th, and 38th USCI regiments, came over the earthworks and dispatched many of the wounded black soldiers. The Rebels also took equipment, uniform parts, and rifles from the dead and wounded, which they used against Draper's attackers.

A combination of a Confederate withdrawal order and a resurgent attack by the Draper's USCT regiments powered the black men over the works pushing out the remaining defenders. As they continued, they did as Butler had earlier requested, they yelled "Remember Fort Pillow!"