Wednesday, September 30, 2015

One Pinch of Owl Dung?

Students of the Civil War are often armed with a plethora of quotes. Some are even familiar to the most casual of enthusiasts. Who can forget, "There stands Jackson like a stone wall;" or "War means fighting, and fighting means killing;" or "May God have mercy on Bobby Lee, for I shall have none;" or "It is well that war is so terrible, or we should grow too fond of it." They go on and on. But one that always makes me chuckle is Samuel D. Sturgis' (pictured above) thoughts of fellow Union general John Pope.

During the Second Manassas Campaign Pope had earned the enmity of not only Confederates such as normally mild-mannered Robert E. Lee, who labeled Pope a "miscreant," the bombastic Kentucky native also riled his fellow officers. At one point in the maneuvering of troops during the campaign Sturgis commandeered a train to move his troops instead of men intended for Pope's forces. When reprimanded by Union railroad man Gen. Herman Haupt for his actions, Sturgis exclaimed "I don't care for John Pope one pinch of owl dung."

So, was this a common phrase of the time (I've never heard it in any other instance)? Or did Sturgis just bring it off the cuff? I'm guessing the derogatory phrase probably just came to Sturgis, but I think it's about time we make it mainstream. I can hear it now, "I don't care for (insert your least favorite political candidate or opposing football coach here) one pinch of owl dung!" Still makes me chuckle.

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Wednesday, September 23, 2015

Ready to March

I never get tired of looking at images from the Liljenquist Family Collection on the Library of Congress website. Of the many many photographs, few of them show soldiers in full marching gear.

This unidentified Union soldier carries a knapsack with rolled blanket. Other equipment shown includes his waist belt, tarred haversack, bayonet scabbard, and cartridge box and sling. I don't see his canteen, but it likely is hidden by his arm resting over his haversack. Tucked in his waist belt looks to be a Smith and Wesson revolver, as well as a knife of some type. His coat is an enlisted man's frock. His headgear is a common Union forage cap.

Just your average common soldier fighting an uncommon war.

Tuesday, September 15, 2015

The William Gaines Family and their Slaves

Today, I was searching for some images for a project I am working on at work. I found the above picture while searching and thought I'd share it on here since it was new to me.

The Library of Congress website description states that this was taken in Hanover County, Virginia, in 1862 on the plantation of Dr.William Gaines. The photographer was George Harper Houghton.

Being curious, I thought I'd look up Gaines in the 1860 census. Interestingly there were two William Gaines listed--both on the same page, so I am guessing they were father and son.

The first "Wm. Gaines" was indeed listed as "Dr. & farmer." He was only twenty-five years old. Only initials are given for this Mrs. Gaines, who was twenty-seven, and their daughter, who was three. Either Gaines accrued a sizable fortune early, or more likely, was provided a good start by his father as he is listed as owning $29,300 in real estate and $11,970 in personal property.

The other Gaines, "Wm. F. Gaines," was fifty-six years old and was a "M.D. & farmer." Mr. Gaines, Sr. had $56,000 in real estate and $54,475 in personal property. His wife "J.G." was forty-seven. The next listed household is that of W.H. Wood, an overseer; presumably the elder Gaines's plantation manager.

William Gaines is shown as owning fifteen slaves in the 1860 slave schedules, living in what looks to be seven slave dwellings. I assume this is Gaines the younger. William F. Gaines owned seventy-four slaves and their twelve slave quarters. I am guessing that those enslaved individuals shown in the photograph above are those of Gaines, the older, but that is purely speculation on my part.

I found that William Gaines, who's date of birth makes it the son, fought in Company I, Fifteenth Virginia Infantry. He enlisted less than a week after Virginia seceded.

Photographer George Harper Houghton apparently took the above image while accompanying soldiers on the Peninsula Campaign from his home state of Vermont. Some of Houghton's amazing work can be seen here.

Tuesday, September 8, 2015

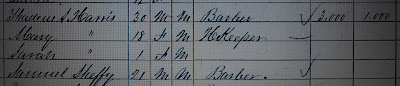

Lexington, Virginia's Antebellum Black Barbers

Since I am searching census records online, it seems best to focus on those of towns and cities, where black barbers are most likely to work. I don't want to totally ignore rural county records, as barbers may live out of town limits and come to those more populated areas to do their work, but at present it makes sense to seek those in urban areas first.

I reported on 1860 census finds in Goodson (Bristol) and Abingdon in Washington County, Virginia in my last post. My next location to search was Lexington in Rockbridge County. I have a soft spot in my heart for Lexington as I completed a graduate fellowship there at the Stonewall Jackson House in the summer of 2004, the wonderful memories of those three months remain with me to the present. Interestingly, while there, I went several times to have hair cut by an elderly African American man. Unfortunately, I cannot remember his name, but I do remember him telling me stories of his service in World War II driving a deuce and a half.

The 1850 Lexington census only consisted of twenty-seven pages, so I worked my way through them rather quickly and found two barbers. They both resided in the household of Edward J. McCampbell, a twenty-five year old lawyer. I assume the men were boarders. One, Thomas Campbell, was listed as a twenty-one year old black man, who was a native of Virginia. The other, Joseph Cooper, was a twenty-five year old mulatto, who was also a native of the Old Dominion. Neither are shown as owning real estate. The 1850 census did not record personal property worth. It is speculation on my part, but perhaps these men rented a shop together and roomed together.

The 1860 census included what appeared to be a set of brothers; or perhaps cousins. Robert Bibey was a twenty-five year old mulatto, who owned $30 in personal property and is listed as not able to read or write. Sauney Bibey was twenty-two years old and was described as mulatto and illiterate as well. Also in the household was Julia Bibey, who was twenty-three years old. Was Julia Bibey Robert and Sauney's sister, or one of the men's wife? She is listed as mulatto like the men, but that is certainly not conclusive either way.

The other 1860 Lexington black barber was Charles Evans. This young man was only fourteen, and is listed as a mulatto. He is not shown with any wealth. However, his is in the household of Hariet Mays or Mayo, a forty-five year old washer woman, who had $30 in personal property. Perhaps Hariet was Charles's mother. Regardless, they lived next door to the Bibeys and Charles likely worked shaving and cutting hair with Roberty and Sauney Bibey.

Image courtesy of the Virginia Military Institute Archives.

Saturday, September 5, 2015

Virginia Antebellum Black Barbers

I'm not sure where I'm going to find the time and energy to do the research and writing, but some preliminary searching in the 1860 Virginia census is turning up a significant amount of promising information on the state's antebellum black barbers. I had made some limited searches as evidenced from previous posts about some mentions of barbers in Richmond newspaper stories and advertisements,but had not started a thorough search of any county until this past week. We'll see if I can keep up the hunt and what comes out of it.

I thought I'd take a start with the Washington County census. Washington County is located in the southwest part of the state and has historic towns in Bristol and Abingdon. I figured that if the Old Dominion is anything like Kentucky, those towns would have a black barber or two. They did. I fact, I located three.

A few other reasons I chose Washington County as a starting place is that I have ancestral connections to the area, and having lived and worked nearby, I thought it would be a interesting point of entry. But, the main reason is that while looking up some information on famed Confederate guerrilla leader John S. Mosby after having visited Warrenton, I came across the listing of barber Christopher Martin (above) on the same census page as Mosby.

Before the war, Mosby worked as an attorney in Goodson (present day Bristol) and covered cases in both Washington County, Virginia, and Sullivan County, Tennessee. In fact, Mosby joined a local regiment called the Washington (County) Rifles before ending up in the cavalry, and then forming his own famous guerrilla battalion.

Martin, like many of the barbers in Kentucky, had accumulated a significant amount of wealth for a free man of color. He is listed with $1000 in real estate and $200 in personal property. Martin's large family included six children. Although teenage sons Albert and Frank do not have occupations listed, I would not be surprised if they served as barber apprentices in their father's shop.

Also in Goodson (Bristol) was William Rucker, who is noted as owning the same amount of wealth as competitor Christopher Martin. Rucker, too, has a teenage son, William Jr., who may have assisted in his father's barber shop. The census indicated that Rucker had been born in North Carolina.

This limited sample group fits many of the same patterns that I had found in my Kentucky research. All of these Washington County barbers were in their thirties, and were all listed as mulatto. I will be interested to see if the number of black and mulatto barbers even out as I increase my findings. Also, all of these men held solid amounts of wealth for the time period.

I'll keep you all posted on what I find as more counties get perused.

Wednesday, September 2, 2015

The Ubiquitous Edmund Ruffin

On our trip Isle of Wight County, and while driving down Highway 10 through Prince George County, I spotted a sign indicating the birthplace of Edmund Ruffin. In my latest post on Ruffin, I mentioned that he seemed to be present a many historic events, such as John Brown's hanging and Fort Sumter. After doing a little more reading, I was reminded that the old "hot spur" was at the Battle of First Manassas, too.

Ruffin wrote about his experience in the war's first big battle in his extensive diary: "I was overtaken by one of Kemper's field pieces, which I was sure was on the route to the battle-field, or to wherever it could do the best service. . . . The officer in command, Sergeant Stewart, knew me, & as passing, invited me to take a seat, the only one vacant, on the cannon, which invitation I gladly accepted." After traveling a short distance on the cannon, the crew stopped. "I most gladly took the opportunity to dismount from my very uneasy & also precarious seat on the cannon & with leave, asked & was granted, seated myself on the gun carriage. My previous ride had been disagreeable to me, as my position must have been ludicrous to anyone enough unoccupied to be an observer." A bumpy ride across a cornfield brought the gun to a halt and Ruffin observed the Union army retreating and the Confederates cheering. Ruffin later learned that Kemper's artillery had been ordered out of the battle due to it hard service during the fight.

However, with the Yankees on the run, the Confederate artillerymen thought it a perfect chance to cause some additional pandemonium. "By order two of Kemper's guns were unlimbered, & quickly ready for firing. I, having before obtained the captain's permission, fired the first of these guns--either 10 or 12 being thus directed, & rapidly fired off. We could not see the effect from our position--but soon some of the enemy were seen escaping by a lateral road to our left, from the first position fired at." Ruffin later learned from battle reports that the shot he fired hit on a stone bridge over Cub Run and forced a wagon to overturn, which clogged the route of Union retreat.

I'm sure the old man couldn't have been happier to see the Yankees fleeing back toward Centreville and Washington D.C. beyond. Ruffin went on to see the fighting at Seven Pines, but he probably never felt quite the same exhilaration as that day at Manassas.

Tuesday, September 1, 2015

Suffering for the Cause

While at Bacon's Castle this past weekend we picked up several brochures they had displayed that highlighted other local historic sites. After driving on to Isle of Wight County and having lunch in the great "Main Street" town of Smithfield, we drove a few more miles to see St. Luke's Church (above). St. Luke's is the oldest church in Virginia. Services began here according to some sources as early 1632.

Taking a leisurely stroll through the cemetery that surrounds the old brick church, I spotted a "Southern Cross" beside one of the graves. Curiosity got the better of me so I walked over to see who was buried there. When I read the name "Emmett M. Morrison," and that he was colonel of the 15th Virginia Infantry Regiment, it didn't help ring any bells in my memory. While there though, I thought I would go ahead a snap a shot his headstone just in case I decided to look him up and to help me remember his name.

Well, what I found in Morrison's service records, and with some online research, provided yet another example of the extent some Confederate soldiers went to in attempt to realize their new nation.

Morrison's grave being located in Isle of Wight is no surprise. He was born there, grew up there, and after the war, he worked and died there.

The 1850 census shows Morrison as a nine year old in his father, Edwin's, household. Edwin Morrison was a hotel keeper and along with his family of six, there were ten other individuals living in what I assume was their hotel. Interestingly, one of the occupants was an eighty year old free black woman named Sabina West. Edwin owned eleven slaves.

I was unable to locate Edwin Morrison in the 1860 census, but he does show up in that year's slave schedules as the owner of fifteen slaves. By that time his son Emmett was attending Virginia Military Institute in Lexington, Virginia.

When Virginia seceded in April of 1861, Edwin was among a number of the cadets sent to Richmond to train the Confederate recruits arriving from across the South. It didn't take long for young Emmett to land in a permanent regiment. With his military skills and knowledge on full display he was elected as the captain of Company C of the 15th Virginia Infantry. He was promoted to major on August 19, 1862, and lieutenant colonel on April 22, 1864, but with the rank dating back to January 24, 1863.

Between young Morrison's promotions from major to lieutenant colonel, the 15th Virginia fought at the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862. During the engagement Morrison took a severe slug wound to his right shoulder. After being attended to at a field hospital he was captured and sent to Fort Henry and then Fort Delaware before he was finally exchanged.

Morrison fought on the Bermuda Hundred line in Pickett's division in the fall and winter of 1864. He reported sick and was admitted to a hospital in Petersburg in January 1865, but soon returned to duty. After resuming his duties, Morrison was captured at Sailor's Creek on April 6, and was sent to Old Capitol Prison and then to Johnson's Island prison. He was released in the summer of 1865 after taking the oath of allegiance.

After the war Morrison returned to his native Isle of Wight County. He married Sarah Wilson in 1872, and became a teacher at Smithfield Academy (which still stands). He later held positions as a surveyor, superintendent of schools, and postmaster. He lived to the old age of ninety, dying in 1932.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)