Saturday, December 26, 2015

Plantation Life - Duties and Responsibilities (Slave Cooking & Food)

The DeBow's Review article made the issue of food for enslaved workers understood to be significant to masters:

"Servants should be well fed. Not on Botany Bay provisions, stale and tainted, unless under convict punishment; not stintedly, unless upon diet; but wholesome and sound, and of this sort enough. Where they are required to cook their own victuals, time and means ought to be afforded them for doing it to the best advantage. Cooking has much to do with how far a given quantity of raw material will go. All alimental properties may be saved and used, or a large part of them thrown away in the process. The best virtues of a piece of meat may be wasted upon a coal or spit, and what would, with skill and economy in its preparation, do for two men, will hardly satisfy the hunger of one. A great chemist has announced to the world a method by which people could subsist on one third of their usual allowance: cook it with threefold more care, and chew it three times as much. In many a cabin the chief article in the kitchen inventory is a wornout corn field hoe. With this, turned up on its eye, the cake is baked; hence the widely-prevalent name of that simplest edible form of Indian meal--the hoe-cake. . . .

Variety in food is healthy as it is pleasant. It keeps up the chemistry of the system. A vegetable garden in common is a good thing: not cultivated in common, for it would not be cultivated at all on the community principle; not used in common, for then it would soon be used up; but laid out of ample size, cultivated and dealt out by authority, for the common benefit. The servant should have an honest interest in the forward roasting ears, the ripe fruit, the melons, potatoes, and fat stock."

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Sunday, December 20, 2015

Plantation Life - Duties and Responsibilities (Slave Clothing)

From that same DeBow's Review issue in 1860 the subject of slave clothing we briefly mentioned:

"Negroes are liable to suffer peculiarly from cold. Their health and comfort that they be well protected. It is not uncommon or unpleasant spectacle to see them half-stripped and basking in the genial rays of their native sun; but a shivering servant is a shame to any master.

Besides the coarse fabrics for working use, it is a commendable custom to furnish occasionally a Sunday or holiday attire. This keeps alive among servants a proper self-respect, and promotes those associations that contribute to their moral improvement, and from which they would otherwise refrain. It takes but little in this way to diffuse a very general gladness over a household or plantation."

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Friday, December 18, 2015

Plantation Life - Duties and Responsibilites (Slave Shelter)

Browsing through an 1860 issue of DeBow's Review I came across an article titled "Plantation Life - Duties and Responsibilities." Among the many topics it covers are food, clothing, and shelter for slaves. Of course, I found the discussion on shelter particularly interesting.

As far as slave housing the author explained: "A glance at the servants' quarter, in town or country, will leave no one in doubt why, when pestilence prevails, it is so fatal to this population; the wonder only is, that they do not oftener suffer pestilence: fortunately, not much of their time is passed in these pent-up and noisome abodes. A large proportion of human diseases is bred in human habitations. When vegetable matter, heat, and moisture combine, there must be present febrile miasma. Bearing this in view, if many masters would survey their servants' cabins, they would immediately go to work, pulling down the old and putting up new ones. It would be a saving in the end. It would soon be saved out of doctor's bills and sick-list. When cholera rages, whitewash is brought into requisition and sanitary regulations established. Why cease to enforce them when the panic subsides? These same causes, of easy prevention, do always, more or less, work sickness and death."

He continued a little later: "After all, one thing still is to be looked to: no house, of what dimensions soever, can be comfortable if crowded. Morality is very directly involved here. The mingling of sexes, or the throwing of aliens and strangers together, in the same house, without reference to the natural grouping of families, is fatal to most domestic virtues."

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Tuesday, December 15, 2015

Waud Sketches Contraband Women

When Civil War photographs are difficult to find on certain subjects, I often turn to sketches. Artists such as Edwin Forbes and Alfred Waud were on the scene at many of the conflict's most important events, and luckily, they captured many scenes of everyday life, too.

In this sketch by Waud, titled "Skedaddlers Hall, Harrisons Landing," a sutler's store of New York's Excelsior Brigade on July 3, 1862, is depicted. This was two days after the Battle of Malvern Hill. Lee's bloody Confederate assaults against Union artillery helped encourage McClellan to retreat to his base of operations on the James River near the boyhood home of former U.S. president William Henry Harrison.

Among all the many individuals in the sketch are three African American women. It is unclear what their role is with this group of soldiers, but perhaps some clues are provided in the image. One of the women sits on a large wooden tub. There appears to be clothing in the tub. Were these women possibly laundresses? It was a common enough occupation for runaway slave women who came into Union lines, and seems the most likely explanation.

A close-up gives us a better view, but little better idea of what is truly in the tub or what the women are indeed doing here. All three wear head wraps. Two wear short sleeve dresses, which of course, would meet the demands of weather on a July 3rd day as well as the job of washer women.

Only one of the womens' faces is clearly visible. She provides a left profile and shows her hair tucked under her head wrap and an earring dangling from her left ear. Her face provides little idea as to her mood or what she thinks of the situation she found herself in.

One has to wonder what her life was like in slavery? What did she do to make her way to the Union army? What was her primary job as a slave? What did she get paid while working for the Yankees? Did she live through the war? If so, what did she do when the war war over? Was she married? Did she have children at this point? Who are her descendants? If so, would she be proud of what they have accomplished?

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Saturday, November 14, 2015

The Reliable Contraband

The "Reliable Contraband," by Edwin Forbes provides an intriguing view of the relationship that sometimes developed between Union soldiers and the African American slaves they encountered in the Southern states. Many Union officers were hesitant to accept so-called contrabands into their lines, especially early in the war. But as the conflict wore on, blacks came to be seen as a double (even triple) positive to the Union forces. Not only did they take away labor from Southerners, but many came to work for the Union, and thus in opposition to their former owners.

In addition to being a valuable work force, former slaves also provided vital information to Union soldiers, otherwise unobtainable. Northern soldiers often encountered the fierce animosity of the Southern white population. Yankee questions as to where roads ran, or how far the nearest town was, were often met with cold silence. However, even before the Emancipation Proclamation, African Americans fully understood that the Union presence in the slaves states would likely doom the institution, and therefore quite willingly offered up any pieces of information that potentially assisted Union success and thus enhanced their chances of freedom.

The image Forbes provides likely shows the meeting of a contraband and what appears to be a Union cavalry officer and soldier near a ramshackle slave quarter. In deference to the white man, the black man tips his hat in respect. The former slave is holding a bucket and is leading a horse, one that probably belonged to his former owner. Pitched beside the quarter are a couple of Federal shelter tents, near which another soldier looks be cleaning his boot off. Behind the quarter a couple of horses are tied to a tree. A couple more horses are behind the shelter tents.

This scene probably played out in countless Southern rural settings. The information that former slaves provided to their eventual liberators would come to serve the Union forces well and assist greatly in their ultimate victory.

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Monday, November 2, 2015

Southern Honor?, or What the Heck Was That?

Southern honor is a subject I find fascinating. The extreme desire to protect one's name and reputation by going to dire lengths is something quite foreign to us. However, I feel like I have a good grasp on why a person might fight a duel or take out an advertisement calling out one's social rival or enemy.

But the above advertisement is beyond my comprehension. It was published in the February 28, 1865, issue of the Richmond Daily Dispatch and placed by John W. Talley of the Third Virginia Cavalry. In it Talley felt the need to publicly call out an anonymous person who wrote Talley a letter accusing the cavalryman of using disrespectful language in a Valentine.

Unless the anonymous person shared Talley's alleged letter with others, what was the purpose of Talley printing such a personal advertisement as this? Why did Talley feel the need to air this seemingly non-public affront? After all, Talley had no idea who even sent the letter claiming the cavalryman's alleged disrespectful language?

Does anyone have any perspective that I am perhaps missing?

Sunday, November 1, 2015

A Touching Personal Advertisement

While browsing through issues of the Richmond Daily Dispatch looking for resolutions issued by Confederate soldiers, I came across the touching personal advertisement above. It is quite unlike anything I have ever seen. In this March 15, 1865 issue, John [McKeehan] of Co. E, 7th Tennessee Infantry placed a personal classified advertisement seeking to locate his brother, Samuel McKeehan. John was sick in Chimborazo Hospital in Richmond and likely thought he was going to die.

Curiosity had me searching Fold3 for the brothers' records. I found them; what little there was to them. There was only one card for John G. McKeehan. It states that he enlisted February 12, 1865 in Bristol, Tennessee. I suspect that the written in date of 1865 is possibly incorrect. However, it may be correct as brother Samuel's enlistment was also listed as February 12, 1865, but noted as enlisting at nearby Carter County, Tennessee. Also in Co. E, was Landon McKeehan, who, too, enlisted in Carter County on February 12. Were all of these men late war conscripts? I'm not sure.

Doing additional research I found the East Tennessee McKeehans in the 1860 census. John is listed as fourteen years old and in the household of W. W. McKeehan. By 1865 he would have been eighteen or nineteen years old. There is a twenty-seven year Samuel in his own neighboring household. Landon McKeehan is also twenty-seven and in a neighboring household, perhaps that of an uncle. Landon may have been a cousin.

I was unable to positively determine if John survived his illness or not. But I did locate a John McKeehan living in Kansas in 1870 who was born in Tennessee and was 24 years old, which matches perfectly with the John in the 7th Tennessee Infantry who laced the ad. Samuel was still living in Carter County in 1870. He was married and had five children.

Saturday, October 31, 2015

Monday, October 26, 2015

Francis Bartow's Manassas Monument

Civil War battlefields that later became National Parks are often filled with monuments to the regiments and individual officers that fought there. The reason many generals have monuments on these battlefields is because they had earned a name and reputation fighting in previous battles. However, there is a monument at the Manassas National Battlefield Park who honors an officer who died in his first battle.

When it was mentioned on my recent extended tour how tragic it would have been to have died in the fighting at, say Sailor's Creek, or Appomattox with Lee's surrender only a few days or even hours away, it made me think. But it also struck me that dying early in the war prevented some soldiers the opportunity to be remembered as well as those that fought in many later battles and earned a respected reputation. For example, what if Thomas Jonathan Jackson had been killed at Manassas instead of "standing like a stonewall?" Would he have all the recognition he eventually received without his effective 1862 Valley Campaign or his significant role in the Battle of Chancellorsville? Not likely.

Francis Bartow's (pictured above) and Bernard Bee's monuments at Manassas honor two soldiers who fell in their first fight. They would not receive other military honors. But it makes one wonder what would they have done if they had lived. Would they have had outstanding careers? Or would they have faded or been transferred to some backwater of the war? We'll never know.

Francis Bartow had a lot to fight for. He was a wealthy attorney who had received about as good of an education as one could get in 19th century America. He married the daughter of a well to do Georgia politician, which added land and slaves to his growing riches. The 1860 census show Bartow owning over 80 slaves on is Chatham County, Georgia plantation.

Bartow started the war as the captain of a Savannah militia company, but was soon elected to the Confederate Provisional Congress. He decided a military career was a better fit and became captain of a company of the 8th Georgia Infantry in May 1861. The following month Bartow was made colonel of the 8th. His leadership would be short, as he was killed in the Manassas fighting on July 21. He fell near the Henry House, which was at the center of the fighting after attempting to rally his troops who had suffered a flanck attack from their Union opponents. He died after reportedly stating, "They have killed me, boys, but never give up the field." His body was returned to Savannah, and that same year a Georgia county was renamed in his honor.

Although Bartow was indeed leading a brigade when he died at Manassas, apparently he never formally received a brigadier general's commission.

Sunday, October 25, 2015

Memorializing Virginia's Colonial History

I apologize for the lack of posts this month, but responsibilities have pulled me in several directions. One of the pleasant responsibilities was guiding a custom tour which took in some non-Civil War sites. Included on the list was Jamestown; site of the first permanent English settlement in America.

On the grounds is an impressive monument (pictured above). The towering granite obelisk honors those early settlers and the colony. It was erected and dedicated on 1907; the 300th anniversary of the founding of the settlement. The monument, called the Memorial Church and Tercentenary Monument, stands resolutely between the Old Towne and New Towne sections of Jamestown Colonial National Historical Park.

Statues to two of Jamestown's most famous personalities also grace the grounds. Inside the outline of the original fort is a monument to Captain John Smith (above), which was also dedicated around the 300th anniversary. Although Smith's actual stay in Jamestown was rather short, his impact on the settlement was significant. A statue to Pocahontas (not shown), Chief Powhatan's daughter, is just outside the fort and near the Memorial Church. Many myths about Pocahontas have emerged over the years since her death in 1617 in England, but her marriage to John Rolfe in 1614 helped create a somewhat more amicable relationship between the colonists and native people, if only briefly.

Starting with an initial purchase of twenty-two and one-half acres of Jamestown Island land in 1893 by Preservation Virginia, the historic site has grown and become a must-see for those wishing to learn more about early white settlements and their contact with Native Americans in Virginia. If you have not been to Jamestown, take time to go and appreciate this important story in our nation's history.

Wednesday, October 14, 2015

Thursday, October 8, 2015

Joel Walker Sweeney's Grave

Appomattox National Historical Park is a wonderful place that I have visited several times. However, I had not taken the time to locate the grave of banjo man Joel Walker Sweeney's grave, which is on the park grounds. This past Tuesday, I enjoyed yet another visit to Appomattox and determined to find it.

Sweeney's grave is quite near where Gen. Robert E. Lee made his last official army headquarters and where he met Gen. Grant the day after the surrender at the McLean House. There are only a handful of marked graves among the simple rail-fenced cemetery. It appears that Sweeney's grave marker is a rather recent placement.

The beginnings of the Appomattox River runs near Sweeney's grave as well. It is difficult to believe that this small stream turns into the broad river it ends up being at Petersburg, and a little further downstream, where it merges into the James River.

Sunday, October 4, 2015

An Unwilling Slave Patroller's Account

Reading through American Slavery As It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses, published in 1839, by abolitionist Theodore Dwight Weld, I came across the account of Hiram White, who had lived in North Carolina for over thirty years, but moved to Illinois, presumably to get away from slavery's influence.

Slavery as an institution of racial control is sometimes overlooked in favor of the economic interests that owners invested in the practice. The amount to which slaves lives were controlled was almost unfathomable to us today living in a era of almost unlimited rights and liberties. Slaves were often required to carry passes when away of their home plantations and were likely to be subjected to random searches both in their quarters and when found out and about at night by patrollers.

But back to our account:

"About the 20th, December, 1830, a report was raised that the slaves of Chatham county, North Carolina, were going to rise on Christmas Day, in consequence of which a considerable commotion ensued among the inhabitants; orders were given by the Governor to the militia captains, to appoint patrolling captains in each district, and orders were given for every man subject to military duty to patrol as their captains should direct. I went two nights in succession, and after that refused to patrol at all. The reason why I refused was this, orders were given to search every negro house for books or prints of any kind, and Bibles and Hymn books were particularly mentioned. And should we find any, our orders were to inflict punishment by whipping the slave until he informed who gave them to him, or how they came by them."

Later in his testimony, White provided a view of the results of the searches:

"At the time of the rumored insurrection above named, the Chatham jail was filled with slaves who were said to be confined in the plot. Without the least evidence of it they were punished in divers [sic] ways; some were whipped, some had their thumbs screwed in a vice to make them confess, but no proof satisfactory was ever obtained that the negroes had ever thought of an insurrection, nor did any so far as I could learn, acknowledge that an insurrection has ever been projected. From this time forth, the slaves were prohibited from assembling together for the worship of God, and many of those who had previously been authorized to preach the Gospel were prohibited."

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Wednesday, September 30, 2015

One Pinch of Owl Dung?

Students of the Civil War are often armed with a plethora of quotes. Some are even familiar to the most casual of enthusiasts. Who can forget, "There stands Jackson like a stone wall;" or "War means fighting, and fighting means killing;" or "May God have mercy on Bobby Lee, for I shall have none;" or "It is well that war is so terrible, or we should grow too fond of it." They go on and on. But one that always makes me chuckle is Samuel D. Sturgis' (pictured above) thoughts of fellow Union general John Pope.

During the Second Manassas Campaign Pope had earned the enmity of not only Confederates such as normally mild-mannered Robert E. Lee, who labeled Pope a "miscreant," the bombastic Kentucky native also riled his fellow officers. At one point in the maneuvering of troops during the campaign Sturgis commandeered a train to move his troops instead of men intended for Pope's forces. When reprimanded by Union railroad man Gen. Herman Haupt for his actions, Sturgis exclaimed "I don't care for John Pope one pinch of owl dung."

So, was this a common phrase of the time (I've never heard it in any other instance)? Or did Sturgis just bring it off the cuff? I'm guessing the derogatory phrase probably just came to Sturgis, but I think it's about time we make it mainstream. I can hear it now, "I don't care for (insert your least favorite political candidate or opposing football coach here) one pinch of owl dung!" Still makes me chuckle.

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Wednesday, September 23, 2015

Ready to March

I never get tired of looking at images from the Liljenquist Family Collection on the Library of Congress website. Of the many many photographs, few of them show soldiers in full marching gear.

This unidentified Union soldier carries a knapsack with rolled blanket. Other equipment shown includes his waist belt, tarred haversack, bayonet scabbard, and cartridge box and sling. I don't see his canteen, but it likely is hidden by his arm resting over his haversack. Tucked in his waist belt looks to be a Smith and Wesson revolver, as well as a knife of some type. His coat is an enlisted man's frock. His headgear is a common Union forage cap.

Just your average common soldier fighting an uncommon war.

Tuesday, September 15, 2015

The William Gaines Family and their Slaves

Today, I was searching for some images for a project I am working on at work. I found the above picture while searching and thought I'd share it on here since it was new to me.

The Library of Congress website description states that this was taken in Hanover County, Virginia, in 1862 on the plantation of Dr.William Gaines. The photographer was George Harper Houghton.

Being curious, I thought I'd look up Gaines in the 1860 census. Interestingly there were two William Gaines listed--both on the same page, so I am guessing they were father and son.

The first "Wm. Gaines" was indeed listed as "Dr. & farmer." He was only twenty-five years old. Only initials are given for this Mrs. Gaines, who was twenty-seven, and their daughter, who was three. Either Gaines accrued a sizable fortune early, or more likely, was provided a good start by his father as he is listed as owning $29,300 in real estate and $11,970 in personal property.

The other Gaines, "Wm. F. Gaines," was fifty-six years old and was a "M.D. & farmer." Mr. Gaines, Sr. had $56,000 in real estate and $54,475 in personal property. His wife "J.G." was forty-seven. The next listed household is that of W.H. Wood, an overseer; presumably the elder Gaines's plantation manager.

William Gaines is shown as owning fifteen slaves in the 1860 slave schedules, living in what looks to be seven slave dwellings. I assume this is Gaines the younger. William F. Gaines owned seventy-four slaves and their twelve slave quarters. I am guessing that those enslaved individuals shown in the photograph above are those of Gaines, the older, but that is purely speculation on my part.

I found that William Gaines, who's date of birth makes it the son, fought in Company I, Fifteenth Virginia Infantry. He enlisted less than a week after Virginia seceded.

Photographer George Harper Houghton apparently took the above image while accompanying soldiers on the Peninsula Campaign from his home state of Vermont. Some of Houghton's amazing work can be seen here.

Tuesday, September 8, 2015

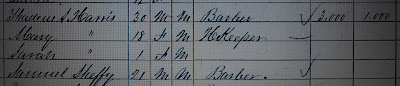

Lexington, Virginia's Antebellum Black Barbers

Since I am searching census records online, it seems best to focus on those of towns and cities, where black barbers are most likely to work. I don't want to totally ignore rural county records, as barbers may live out of town limits and come to those more populated areas to do their work, but at present it makes sense to seek those in urban areas first.

I reported on 1860 census finds in Goodson (Bristol) and Abingdon in Washington County, Virginia in my last post. My next location to search was Lexington in Rockbridge County. I have a soft spot in my heart for Lexington as I completed a graduate fellowship there at the Stonewall Jackson House in the summer of 2004, the wonderful memories of those three months remain with me to the present. Interestingly, while there, I went several times to have hair cut by an elderly African American man. Unfortunately, I cannot remember his name, but I do remember him telling me stories of his service in World War II driving a deuce and a half.

The 1850 Lexington census only consisted of twenty-seven pages, so I worked my way through them rather quickly and found two barbers. They both resided in the household of Edward J. McCampbell, a twenty-five year old lawyer. I assume the men were boarders. One, Thomas Campbell, was listed as a twenty-one year old black man, who was a native of Virginia. The other, Joseph Cooper, was a twenty-five year old mulatto, who was also a native of the Old Dominion. Neither are shown as owning real estate. The 1850 census did not record personal property worth. It is speculation on my part, but perhaps these men rented a shop together and roomed together.

The 1860 census included what appeared to be a set of brothers; or perhaps cousins. Robert Bibey was a twenty-five year old mulatto, who owned $30 in personal property and is listed as not able to read or write. Sauney Bibey was twenty-two years old and was described as mulatto and illiterate as well. Also in the household was Julia Bibey, who was twenty-three years old. Was Julia Bibey Robert and Sauney's sister, or one of the men's wife? She is listed as mulatto like the men, but that is certainly not conclusive either way.

The other 1860 Lexington black barber was Charles Evans. This young man was only fourteen, and is listed as a mulatto. He is not shown with any wealth. However, his is in the household of Hariet Mays or Mayo, a forty-five year old washer woman, who had $30 in personal property. Perhaps Hariet was Charles's mother. Regardless, they lived next door to the Bibeys and Charles likely worked shaving and cutting hair with Roberty and Sauney Bibey.

Image courtesy of the Virginia Military Institute Archives.

Saturday, September 5, 2015

Virginia Antebellum Black Barbers

I'm not sure where I'm going to find the time and energy to do the research and writing, but some preliminary searching in the 1860 Virginia census is turning up a significant amount of promising information on the state's antebellum black barbers. I had made some limited searches as evidenced from previous posts about some mentions of barbers in Richmond newspaper stories and advertisements,but had not started a thorough search of any county until this past week. We'll see if I can keep up the hunt and what comes out of it.

I thought I'd take a start with the Washington County census. Washington County is located in the southwest part of the state and has historic towns in Bristol and Abingdon. I figured that if the Old Dominion is anything like Kentucky, those towns would have a black barber or two. They did. I fact, I located three.

A few other reasons I chose Washington County as a starting place is that I have ancestral connections to the area, and having lived and worked nearby, I thought it would be a interesting point of entry. But, the main reason is that while looking up some information on famed Confederate guerrilla leader John S. Mosby after having visited Warrenton, I came across the listing of barber Christopher Martin (above) on the same census page as Mosby.

Before the war, Mosby worked as an attorney in Goodson (present day Bristol) and covered cases in both Washington County, Virginia, and Sullivan County, Tennessee. In fact, Mosby joined a local regiment called the Washington (County) Rifles before ending up in the cavalry, and then forming his own famous guerrilla battalion.

Martin, like many of the barbers in Kentucky, had accumulated a significant amount of wealth for a free man of color. He is listed with $1000 in real estate and $200 in personal property. Martin's large family included six children. Although teenage sons Albert and Frank do not have occupations listed, I would not be surprised if they served as barber apprentices in their father's shop.

Also in Goodson (Bristol) was William Rucker, who is noted as owning the same amount of wealth as competitor Christopher Martin. Rucker, too, has a teenage son, William Jr., who may have assisted in his father's barber shop. The census indicated that Rucker had been born in North Carolina.

This limited sample group fits many of the same patterns that I had found in my Kentucky research. All of these Washington County barbers were in their thirties, and were all listed as mulatto. I will be interested to see if the number of black and mulatto barbers even out as I increase my findings. Also, all of these men held solid amounts of wealth for the time period.

I'll keep you all posted on what I find as more counties get perused.

Wednesday, September 2, 2015

The Ubiquitous Edmund Ruffin

On our trip Isle of Wight County, and while driving down Highway 10 through Prince George County, I spotted a sign indicating the birthplace of Edmund Ruffin. In my latest post on Ruffin, I mentioned that he seemed to be present a many historic events, such as John Brown's hanging and Fort Sumter. After doing a little more reading, I was reminded that the old "hot spur" was at the Battle of First Manassas, too.

Ruffin wrote about his experience in the war's first big battle in his extensive diary: "I was overtaken by one of Kemper's field pieces, which I was sure was on the route to the battle-field, or to wherever it could do the best service. . . . The officer in command, Sergeant Stewart, knew me, & as passing, invited me to take a seat, the only one vacant, on the cannon, which invitation I gladly accepted." After traveling a short distance on the cannon, the crew stopped. "I most gladly took the opportunity to dismount from my very uneasy & also precarious seat on the cannon & with leave, asked & was granted, seated myself on the gun carriage. My previous ride had been disagreeable to me, as my position must have been ludicrous to anyone enough unoccupied to be an observer." A bumpy ride across a cornfield brought the gun to a halt and Ruffin observed the Union army retreating and the Confederates cheering. Ruffin later learned that Kemper's artillery had been ordered out of the battle due to it hard service during the fight.

However, with the Yankees on the run, the Confederate artillerymen thought it a perfect chance to cause some additional pandemonium. "By order two of Kemper's guns were unlimbered, & quickly ready for firing. I, having before obtained the captain's permission, fired the first of these guns--either 10 or 12 being thus directed, & rapidly fired off. We could not see the effect from our position--but soon some of the enemy were seen escaping by a lateral road to our left, from the first position fired at." Ruffin later learned from battle reports that the shot he fired hit on a stone bridge over Cub Run and forced a wagon to overturn, which clogged the route of Union retreat.

I'm sure the old man couldn't have been happier to see the Yankees fleeing back toward Centreville and Washington D.C. beyond. Ruffin went on to see the fighting at Seven Pines, but he probably never felt quite the same exhilaration as that day at Manassas.

Tuesday, September 1, 2015

Suffering for the Cause

While at Bacon's Castle this past weekend we picked up several brochures they had displayed that highlighted other local historic sites. After driving on to Isle of Wight County and having lunch in the great "Main Street" town of Smithfield, we drove a few more miles to see St. Luke's Church (above). St. Luke's is the oldest church in Virginia. Services began here according to some sources as early 1632.

Taking a leisurely stroll through the cemetery that surrounds the old brick church, I spotted a "Southern Cross" beside one of the graves. Curiosity got the better of me so I walked over to see who was buried there. When I read the name "Emmett M. Morrison," and that he was colonel of the 15th Virginia Infantry Regiment, it didn't help ring any bells in my memory. While there though, I thought I would go ahead a snap a shot his headstone just in case I decided to look him up and to help me remember his name.

Well, what I found in Morrison's service records, and with some online research, provided yet another example of the extent some Confederate soldiers went to in attempt to realize their new nation.

Morrison's grave being located in Isle of Wight is no surprise. He was born there, grew up there, and after the war, he worked and died there.

The 1850 census shows Morrison as a nine year old in his father, Edwin's, household. Edwin Morrison was a hotel keeper and along with his family of six, there were ten other individuals living in what I assume was their hotel. Interestingly, one of the occupants was an eighty year old free black woman named Sabina West. Edwin owned eleven slaves.

I was unable to locate Edwin Morrison in the 1860 census, but he does show up in that year's slave schedules as the owner of fifteen slaves. By that time his son Emmett was attending Virginia Military Institute in Lexington, Virginia.

When Virginia seceded in April of 1861, Edwin was among a number of the cadets sent to Richmond to train the Confederate recruits arriving from across the South. It didn't take long for young Emmett to land in a permanent regiment. With his military skills and knowledge on full display he was elected as the captain of Company C of the 15th Virginia Infantry. He was promoted to major on August 19, 1862, and lieutenant colonel on April 22, 1864, but with the rank dating back to January 24, 1863.

Between young Morrison's promotions from major to lieutenant colonel, the 15th Virginia fought at the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862. During the engagement Morrison took a severe slug wound to his right shoulder. After being attended to at a field hospital he was captured and sent to Fort Henry and then Fort Delaware before he was finally exchanged.

Morrison fought on the Bermuda Hundred line in Pickett's division in the fall and winter of 1864. He reported sick and was admitted to a hospital in Petersburg in January 1865, but soon returned to duty. After resuming his duties, Morrison was captured at Sailor's Creek on April 6, and was sent to Old Capitol Prison and then to Johnson's Island prison. He was released in the summer of 1865 after taking the oath of allegiance.

After the war Morrison returned to his native Isle of Wight County. He married Sarah Wilson in 1872, and became a teacher at Smithfield Academy (which still stands). He later held positions as a surveyor, superintendent of schools, and postmaster. He lived to the old age of ninety, dying in 1932.

Sunday, August 30, 2015

More Virginia Slave Dwellings

Yesterday, Michele and I took a drive down to Surry County to visit Bacon's Castle. It was a wonderful trip fill with lots of great history. Bacon's Castle is the oldest brick house in Virginia and is the only example of Jacobean architecture in the United States. It was built by Arthur Allen in the mid-1600s. The house stayed in the Arthur family for many years before it devolved to the Hankins family, who operated the plantation during the Civil War years.

On the property are a number of out buildings, including a mid-19th century slave dwelling and smokehouse. The slave quarter is a typical two story duplex frame and clapboard design.

However, instead of central chimney shared by the two apartments, each gabled end had its own chimney. Each apartment has its own door entrance.

An interesting feature were the small upper-level two-over-two windows. The building was not guest accessible, so I was unable to inspect the upper story to see if they included a fireplace as did the ground floor.

On our drive back to Petersburg we stopped at the City Point Unit of Petersburg National Battlefield in Hopewell. Here the National Park Service interprets the Union army's supply base during the Petersburg Campaign, as well as Appomattox Manor, the Eppes family plantation. On its grounds are several period outbuildings. Shown above is the laundry (left) and kitchen (right) building. Similar to the structure at Bacon's Castle, it had two sections. The laundry side had a stairway to the upper-level, although it was also inaccessible. A smokehouse stands to the building's left.

The story of the Richard Eppes family and his scores of slaves was fascinatingly told to us by park ranger Emmanuel Dabney. Eppes owned land on several non-contiguous plantations, but lived at Appomattox Manor until the summer of 1862, when he and his family fled to the safety of Petersburg as the Union army made its toward Richmond during the Peninsula Campaign. Many of Eppes' slaves used the opportunity to grasp their freedom.

The final slave dwelling I photographed this weekend is located in Sutherland, which is just southwest of Petersburg. Once known as Sutherland Station, it was on the Southside Railroad. Fighting occurred here during the April 2, 1865 Union army breakthrough as they neared their goal of capturing the rail line. The slave dwelling rests behind the Fork Inn, also known as the Sutherland Tavern, once a stagecoach rest stop, hotel, and tavern built in 1803. The property was owned by Elizabeth Sutherland during the Civil War.

Ms. Sutherland appears in the 1860 census as seventy-five years old. She is listed as being involved with "Farming and Private Inn and Tavern" business.She owned $9,000 in real estate and $21,300 in personal property. She owned twenty slaves, ranging in age from seventy-five to ten months, who lived in three slave dwellings.

Although often overlooked in favor of their more impressive "big houses," these structures are important pieces of Virginia history that all appear to be safe at present. Hopefully these buildings will continue to be preserved and interpreted so we can better understand and appreciate the lives of those who lived and toiled long hours at these sites.

Wednesday, August 26, 2015

Sketches of Union Army Mules

"A Tough Customer. Army Mule," by Edwin Forbes. Rappahanock Station, Virginia, February 5, 1864.

"An Army Mule." Culpeper Courthouse, Virginia, September 28, 1863.

"The Meditative Mule." Culpeper Courthouse, Virginia, September 28, 1863.

"A Played-Out Mule in Hospital." Rappahannock Station, February 5, 1864.

Images courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Tuesday, August 25, 2015

The Mule Driver

"The Mule Driver," by Edwin Forbes, November 23, 1863 at Kelly's Ford, Virginia.

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Monday, August 24, 2015

Edmund Ruffin's Losses

Few men wanted Southern secession, or did more to try to make it happen, than Virginian Edmund Ruffin. The long-haired old man's appearance at Harpers Ferry shortly after John Brown's raid and his reappearance at the abolitionist's hanging were not by coincidence. He wanted to witness history in the making. Later, he was at Fort Sumter's bombardment as well. Some claimed he pulled the lanyard to fire the first shot.

During the war, Ruffin lost one of his plantation homes to Yankee arsons and his slaves absconded. But if Edmund Ruffin knew anything (and he knew plenty) he knew loss. Two of his children had died as mere babies, his wife had died, and three grandchildren had died. Three of his adult daughters died, and one of his daughter-in-laws, who he considered a daughter, had died.

However, the death of Ruffin's second son, Julian, was especially hard on the old fire-eater. Julian was born in 1821 in Prince George County. As a young man he had helped his father establish the Southern Magazine and Monthly Review. Julian was obviously proud of his father's influence and contributions to Southern nationalism, for in 1861, Julian named a newborn son, after grandpa and his adventures; Edmund Sumter Ruffin.

Julian was a sergeant in Company B, 12th Battalion of Virginia Light Artillery when the end came. His service records indicate he enlisted the unit in Petersburg on August 10, 1863 for the duration of the war. Apparently Julian had served in a different unit previously. Julian's service did not last for the duration of the war though. He was killed in the fighting at Drewry's Bluff on May 16, 1864. With a broken heart and seemingly in denial Edmund Ruffin penned in his diary on May 23: "My mind cannot take in the momentous fact, nor my perceptions approach to the measure of reality."

Ruffin could not take much more, and when Confederate defeat finally became a reality, he ended his ruined world by his own hand. On June 17, 1865, he took time to write in his diary: "I here declare my unmitigated hatred to Yankee rule-to all political, social & business connection with Yankees-& to the Yankee race. Would that I could impress these sentiments, in their full force, on every living southerner, & bequeath them to every one yet to be born! May such sentiments be held universally in the outraged & down-trodden South, though in silence & stillness, until the now far-distant day shall arrive for just retribution for Yankee usurpation, oppression, & atrocious outrages-& for deliverance & vengeance for the now ruined, subjugated, & enslaved Southern States!"

Using a stick to trigger his weapon, Ruffin's gun misfired on first attempt. He recapped the piece and was successful in his second try. The old hot-spur was buried on his former plantation, Marlborough, in Hanover County, suffering no more losses.

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Saturday, August 22, 2015

Henry A. Wise's Loss

Wanting to learn more about Virginia's enigmatic politician, Henry A. Wise, I recently completed reading Craig M. Simpson's 1985 book, A Good Southerner: The Life of Henry A. Wise of Virginia. I enjoyed the book and found Wise to be as an intriguing personality as I imagined.

You might remember that Wise was governor of the Old Dominion when John Brown struck at Harpers Ferry in 1859. The book's chapter on Wise and Brown was quite fascinating. Although Wise certainly was at odds with Brown's ideals of racial egalitarianism, the governor had a healthy respect for Brown's courage and commitment to his cause. One might even say that Wise admired Brown.

Wise was succeeded as governor by John Letcher, but his political influence continued. He strongly encouraged the state's secession during its April 1861 convention. When war broke out, Wise, although in his mid-fifties, raised a combined infantry, artillery and cavalry unit appropriately named Wise's Legion. In the summer of 1861, Wise was made a brigadier general. At best, Wise had a checkered track record during the war. His touchiness and honor-bound nature caused him to clash any fellow officers who presented the slightest offense. An 1861 foray into Western Virginia and his inability to work with fellow former governor Gen. John Floyd serves a perfect example.

In early 1862, Wise was transferred to North Carolina. There, he immediately rubbed Gen. Benjamin Huger the wrong way. On February 8, in a fight at Roanoke Island while Wise was sick, his oldest son Obadiah Jennings Wise, a former editor of the Richmond Enquirer, was killed in the battle. Wise the younger was born in 1831, and like his father, held honor most high. Before the war Obadiah fought several duels, some of which came at the defense of his father and his political policies.

Obie, as he was sometimes known, was part of the Richmond Light Infantry Blues, a local militia unit that dated back to 1789. During the Civil War the Blues became Company A of the 46th Virginia Infantry. Apparently Obie was hit in the wrist of his sword-carrying arm while leading his company in the fight at Roanoke Island. Quickly bandaging the injury, he soon received a mortal wound.

Thus, Henry A. Wise not only suffered defeat in northeastern North Carolina, he lost what some considered his favorite son. Obie's body was recovered and when father saw son, Wise exclaimed, "Oh, my brave boy, you have died for me, you have died for me." Obie was buried in Hollywood Cemetery. Father joined son in Hollywood in 1876.

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Friday, August 21, 2015

Wade Hampton's Loss

My continuing study of the Petersburg Campaign has brought a new admiration for the military skills of Wade Hampton. Whether displaying his daring in carrying out the Beefsteak Raid, or his tactical ability at Reams Station, Hampton's cavalry was a proven commodity for Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia.

Wade Hampton sacrificed more than just his enormous fortune for the Confederate cause; he lost a son. At the Battle of Hatcher's Run in February 1864, Lt. Preston Hampton was cut down in the fighting. It is difficult to imagine the pain Hampton must have felt in learning the sad news. In a kind attempt to sooth the mourning father, Gen. Lee wrote the cavalryman. Lee had intimately experienced a similar loss when his daughter Annie died in 1862 at age twenty-three.

Lee wrote:

"My dear General, I grieve with you at the loss of your gallant son. So young, so brave, so true. I know how much you must suffer. Yet, think of the great gain to him; how changed his condition, how bright his future. We must labor in the charge before us, but for him I trust is rest and peace for I believe our merciful God takes us when it is best for us to go. He is now safe from all harm and from all evil and nobly died in the defense of the rights of his country. May God support you under your great affliction and give you strength to bear the trials He may impose on you. Truly your friend, R.E. Lee"

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Tuesday, August 18, 2015

Gen. Cullen Battle's Grave

Have you ever wondered where you will rest in peace? I know, that's a pretty morbid thought. But, I admit, I've wondered. Will it be in the area where I last reside? Or, will I find myself in a generations-old traditional family plot?

Similarly, I sometimes wonder why certain people end up in certain cemeteries. Today, I was over at Petersburg's Blandford Cemetery with a colleague doing some preliminary research on project. One of the graves we visited was that of Confederate General Cullen Andrews Battle. Doing some quick thinking of what I knew of Battle, I found myself at a loss as to why he was buried in Petersburg.

Cullen Battle was born in Hancock County, Georgia, in 1829, but moved with his family to Eufala, Alabama as a boy. After studying at the University of Alabama, Battle read law and was admitted to the bar in 1852. A tried and true secessionist, Battle was close friends with Alabama's leading fire-eater, William Lowndes Yancey. After John Brown's raid, Battle raised a local militia unit and offered its services to Virginia. However, Virginia Governor Henry A. Wise already had enough in-state militia. Battle's unit continued to drill though and maintained a readiness as sectional tensions increased.

When war finally came in 1861, Battle was made major of the 3rd Alabama Infantry. The 3rd eventually made their way to Virginia and fought during the Peninsula Campaign, at South Mountain, and Antietam. For competent service, Battle was promoted to colonel of the 3rd at the end of 1862.

Battle received promotion to brigadier general in February 1864, taking command of Gen. Robert E. Rodes's former brigade. Battle missed a good deal of service due to injuries and illness. After missing time in the summer of 1864 for dysentery, he returned but was wounded at the Battle of Cedar Creek that fall. That wound kept the general out of commission for the remainder of the war. Although major general is listed on his headstone, it appears that promotion was never made official.

In 1880, Battle resettled in New Bern, North Carolina, and edited a newspaper. Later, he resided in Greensboro, North Carolina, where he died at age 75 in 1905 .

So, why wasn't Battle buried in Greensboro, New Bern, or even back in Alabama? The answer it seems was just a wish. Apparently, Battle's son, Henry, a Petersburg minister, desired to have his father's body be brought to and buried in the Cockade City. Sometimes it is as simple as that.

Thursday, August 13, 2015

A Sample of Warrenton's Town Slave Quarters

My visit to Warrenton had me seeking out evidence of the town's antebellum slave life. I was a little surprised it was actually not too difficult to find. While I only took a hand full of shots of what appeared to be surviving slave quarters, there were a number more dotting the town's landscape, often behind beautiful historic homes.

Parking at the town's visitor center put us adjacent to what is known as the Mosby House. And behind the Mosby House was the two story building pictured above. Although I did not go in the building, if I had to guess, I would wager that the right side door of the building entered into what served as the home's kitchen and the left door probably when up stairs to an apartment room. While many slave quarters that I have encountered in Virginia are two story structures, most are more horizontally oriented. I found it an extremely interesting design.

A short walk across the yard was what probably served as a smokehouse. This square-shaped brick building with a pitched-point roof is common for Virginia smokehouses.

Although the home is called the Mosby House, it was actually built by Edward Spillman, a judge, in 1859. The famed Confederate guerrilla leader Col. John Singleton Mosby owned the home after the Civil War. Later, Confederate general Eppa Hunton owned the home.

Walking down a side street I noticed the above brick building. It, too, was likely a kitchen and house slave/cook's quarters. It looks like it has been converted into a small home office or guest apartment.

The small frame building shown above fits the description of a town slave quarters. The structure has had a few alterations and additions to it but it was quite small as can be seen when comparing it to the car parked next to it.

Now I am curious to explore some other old Virginia towns to see if Warrenton's town slave quarters are just uncommonly common.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)