I had remembered seeing The Colors of Courage: Gettysburg's Forgotten History - Immigrants, Women, and African Americans in the Civil War's Defining Battle by Margaret S. Creighton in our bookstore at work when it first came out back around 2005-2006. But already having a number of books on Gettysburg, I decided to pass on it at that time. Then, in a recent issue of the Civil War Monitor magazine, a panel of historians were asked to offer their favorite books on Gettysburg, and a number of them included it among their choices. With those endorsements, I searched and found an inexpensive copy online and added it to my library. When I suggested it to our book club at work for our next group read, it was selected. And having sometime over the holidays I dove in and finished it. Wow! I'm glad all of those above related circumstances worked out the way they did, because it all led me to an excellent book.

The Colors of Courage, as the subtitle suggests, takes a non-traditional approach to the Gettysburg experience. While there are obvious connections to the military history of the battle, especially where it concerns German soldiers of the XI Corps of the Army of the Potomac and with references to the immigrants among the Louisiana Tigers, the focus is much more on social and cultural history. What Creighton attempts to do, and I believe she fully succeeds, is to tell those other stories of how the campaign and battle also effected people who were not traditional combatants.

Her look into the world of women in the town of Gettysburg is fascinating! With many of the town's men already in the Union army or fleeing the chance of capture in the advance of Gen. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia, it was the women of the community to were largely left to deal with the Confederate invasion. It was they who tried to hide the cows, hogs, and preserves; it was they who had to feed the hungry soldiers of both armies; it was they who braved the battle as it spread through the town; and it was they who were often left to nurse the wounded of both sides, and even bury the dead.

The important third leg of Creighton's study is the African American community of Gettysburg. Due to the location of Gettysburg, it was an often traveled route for fugitive slaves in the decades before the Civil War, and for many of those who had attained their freedom, it became their new home. Often forced to work in service occupations and largely segregated to their own corner of the community, they nevertheless provided invaluable labor for the town and developed a rather close-knit community built around church and racial solidarity. When Confederates started rounding up both free people as well as fugitive slaves in the region, many of Gettysburg's blacks were forced to flee to areas further north. Some who had few options of mobility or the time required to get away stayed and braved the storm.

This all makes for an amazing story of struggle and perseverance. Creighton's well-written book incorporates many different sources of information: military reports, newspaper accounts, letters, journals, and oral histories, all help provide the accounts she chooses to tell. This book is significant because it gives us those missing pieces of the puzzle that the traditional military histories too often leave out.

The actions of armies do not only have repercussions for the belligerent opposing forces, they also have long-term effects on the communities where they happen to fight. This is the story of how immigrants, women, and African Americans handled (and also remembered) their part of the Gettysburg storm. I highly recommend it!

Monday, December 31, 2018

Saturday, December 29, 2018

Gettysburg's Black Barber in 1860

I've been reading Margaret S. Creighton's excellent book, The Colors of Courage: Gettysburg's Forgotten History - Immigrants, Women, and African Americans in the Civil War's Defining Battle, and happened across an interesting comment. In her research, she found a comment from someone that mentioned something to the effect that after the battle they could not find a waiter to serve a meal or a barber for a haircut or shave.

Why were there so few black people in Gettysburg, well, Creighton does a fantastic job of explaining that story. During the Army of Northern Virginia's invasion of Pennsylvania the Confederates purposely sought out and captured African Americans with the intention of taking them back to the Confederate states for laborers or to sell.

Gettysburg's geographical location, being in southern Pennsylvania, only a few miles from slaveholding Maryland, ensured frequent visits by slave catchers during the decades before the Civil War. The black people who came to call Gettysburg home, whether free or fugitive, felt constant threats of becoming slaves by hook or crook. When these black people heard about Gen. Lee's invasion and that they were taking blacks prisoners, most African Americans fled to more safe points to the north. Harrisburg, the state capital, was a particularly popular landing spot.

In the book Creighton explains that Gettysburg's black population in 1860 included some 200 souls. I was curious to see if there were black barbers among their inhabitants. So, last evening I spent a few minutes scrolling through the 60 pages of the town's manuscript census.

African Americans claimed several occupations in Gettysburg in 1860. There were blacksmiths, shoemakers, day laborers, servants, a brick maker, a confectioner, a janitor, a hostler, a teamster, among several other jobs, and a few with no listed occupations. However, I only found one barber: Solomon Steevens.

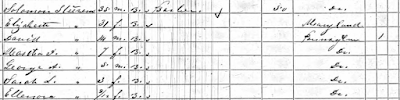

Steevens appears in the 1860 census as a 35 year old black man who had personal property worth $50.00 and was born in Pennsylvania. In Stevens's household were his wife, Elizabeth (31) born in Maryland, sons David (14) and George (5), daughters Aletha (7), Sarah (3), and Ellenora (8 mo.). All of the children were born in Pennsylvania, and eldest son David attended school during the 1860 year.

I was unable to find Solomon Steevens in the 1870 census to see if carried on his pre-war occupation into the Reconstruction years. If anyone has additional information on Solomon or his family, I would be most interested to learn more about his story.

Tuesday, December 25, 2018

Books I Read in 2018

Last December I started the tradition of sharing a complete list of books that I during the year, so I thought that since it doesn't look like I'll be finishing any more by the end of this year that I would share the 2018 version here on Christmas Day. Like last year, I'll highlight those that I found particularly informative, enjoyable, or otherwise really liked. Here goes:

1. Break Beats in the Bronx: Rediscovering Hip Hop's Early Years by Joseph C. Ewoodzie

2. An Uncommon Soldier: The Civil War Letters of Sarah Rosetta Wakeman by Lauren Cook Burgess

3. The Black Family in Slavery and Freedom, 1750-1925 by Herbert Gutman

4. Unholy Sabbath: The Battle of South Mountain by Brian Matthew Jordan

5. A Union Indivisible: Secession and the Politics of Slavery in the Border South by Michael D. Robinson

6. Madness Rules the Hour: Charleston, 1860 and the Mania for War by Paul Starobin

7. The American Dreams of John B. Prentis, Slave Trader by Kari J. Winter

8. Stark Mad Abolitionists: Lawrence, Kansas, and the Battle Over Slavery in the Civil War Era by Robert K. Sutton.

9. The F Street Mess: How Southern Senators Rewrote the Kansas-Nebraska Act by Alice Elizabeth Malavasic

10. Battle Hymns: The Power and Popularity of Music in the Civil War by Christian McWhirter

11. Grant by Ron Chernow

12. Bound to the Fire: How Virginia's Enslaved Cooks Helped Invent American Cuisine by Kelley F. Deetz

13. The Great Fire of Petersburg, Virginia by Tamara J. Eastman

14. The Aftermath of Battle: The Burial of the Civil War Dead by Meg Groeling

15. The Thin Light of Freedom: The Civil War and Emancipation in the Heart of America by Edward Ayers

16. Great Crossings: Indians, Settlers, and Slaves in the Age of Jackson by Christina Snyder

17. Your Brother in Arms: A Union Soldier's Odyssey by Robert C. Plumb

18. Colored Travelers: Mobility and the Fight for Citizenship before the Civil War by Elizabeth S. Pryor

19. A Melancholy Affair at the Weldon Railroad: The Vermont Brigade, June 23, 1864 by David Farris Cross

20. Letters to Amanda: The Civil War Letters of Marion Hill Fitzpatrick, Army of Northern Virginia, edited by Jeffrey Lowe and Sam Hodges

21. Word by Word: Emancipation and the Act of Writing by Christopher Hager

22. Petersburg to Appomattox: The End of the War in Virginia, edited by Caroline Janney

23. Marching Home: Union Veterans and their Unending Civil War by Brian Matthew Jordan

24. Southern Pamphlets on Secession: November 1860 to April 1861, edited by Jon L. Wakelyn

25. We Were in Power Eight Years: An American Tragedy by Ta-Nehisi Coates

26. Masterless Men: Poor Whites and Slavery in the Antebellum South by Kari Leigh Merritt

27. The Ghosts of Guerrilla Memory by Matthew C. Hulbert

28. Frederick Douglass: America's Prophet by D. H. Dilbeck

29. A Campaign of Giants: The Battle for Petersburg, Vol. 1, The Crossing of the James to the Crater by A. Wilson Greene

30. Fighting Means Killing: Civil War Soldiers and the Nature of Combat by Jonathan Steplyk

31. Strike the Blow for Freedom: The 6th United States Colored Infantry by James M. Paradis

32. Civil War Logistics: A Study of Military Transportation by Earl J. Hess

33. Almost Free: A Story about Family and Race in Antebellum Virginia by Eva Sheppard Wolf

34. Inglorious Passages: Noncombat Deaths in the American Civil War by Brian Steel Wills

35. Confederate Supply by Richard D. Goff

36. My Brother's Keeper: African Canadians and the American Civil War by Brian Prince

37. Dear Ones at Home: Letters from Contraband Camps, edited by Henry L. Swint

38. The Color of Christ: The Son of God and the Saga of Race in American by Edward J. Blum and Paul Harvey

39. The Loyal Republic: Traitors, Slaves, and the Remaking of Citizenship in Civil War America by Erik Mathisen

40. A Nation Under Our Feet: Black Political Struggles in the Rural South from Slavery to the Great Migration by Steven Hahn

41. Secessionists and Other Scoundrels: Selections from Parson Brownlow's Book, edited by Stephen V. Ash

42. The Confederacy is on Their Way Up the Spout: Letters to South Carolina, 1861-1864, edited by J. Roderick Heller and Carolynn A. Heller

43. Five for Freedom: The African American Soldiers in John Brown's Army by Eugene L. Meyer

45. John Brown Speaks: Letters and Statements from Charlestown, edited by Louis DeCaro, Jr.

46. Be Free or Die: The Amazing Story of Robert Smalls' Escape from Slavery to Union Hero by Cate Lineberry

47. Don't Hurry Me Down to Hades: The Civil War in the Words of Those Who Lived It by Susannah J. Ural

48. Slavery in the Clover Bottoms: John McClain;s Narrative of His Live in Slavery and during the Civil War, edited by Jan Furman

49. Lincoln's Loyalists: Union Soldiers from the Confederacy by Richard Nelson Current

50. A Fierce Glory: Antietam - The Desperate Battle that Saved Lincoln and Doomed Slavery by Justin Martin

51. No Freedom Shrieker: The Civil War Letters of Union Soldier Charles Biddlecom, edited by Katherine Aldridge

52. Ring Shout, Wheel About: The Racial Politics of Music and Dance in North American Slavery by Katrina Dyonne Thompson

53. The Field of Blood: Violence in Congress and the Road to Civil War by Joanne B. Freeman

54. Civil War Barons: The Tycoons, Entrepreneurs, Inventors, and Visionaries Who Forged Victory and Shaped a Nation by Jeffry D. Wert

55. Honoring the Civil War Dead: Commemoration and the Problem of Reconciliation by John R. Neff

56. Calculating the Value of the Union: Slavery, Property Rights, and the Economic Origins of the Civil War by James L. Huston

57. Hood's Texas Brigade: The Soldiers and Families of the Confederacy's Most Celebrated Unit by Susanah J. Ural

58. Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom by David W. Blight

59. The Colors of Courage: Gettysburg's Forgotten History - Immigrants, Women, and African Americans in the Civil War's Defining Battle by Margaret S. Creighton

60. From "Superman" to Man by Joel Augustus Rogers

Well, I fell one book short of last year's total of 61, but completing better than a book a week is not too bad. 2019 has a number of great history releases coming, and there is always my ever-growing "to be read" shelf. Merry Christmas! And happy reading in the New Year!

Monday, December 24, 2018

Just Finished Reading - Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom

Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom by David W. Blight was one of my top three anticipated books of 2018. The problem with anticipating books (and movies and albums) is that sometimes they let you down. This one certainly did not let me down.

I had read Douglass's three autobiographies, as well as the William McFeely biography, along with a host of other studies on Douglass over the last two decades, but none of them come close to the research, narration, and analysis that Blight provides. As one might imagine choosing what to put in and leave out about such an accomplished man's life can be quite the challenge, and although Blight uses over 750 pages to tell Douglass's amazing story, he crafts it in such a way that the abolitionist's life story melds seamlessly from one decade to the next and from one cause to the next.

What this book really made clear to me is that Douglass was a life-long fighter. Blight does a fantastic job of telling about Douglass's enslaved experience and how he developed almost an addiction to reading and learning as a boy. His transition from fugitive to abolitionist spokesperson and then move from Garrisonian moral suasion proponent to practical activist are explained so well by Blight. Douglass's life of struggle to better all humanity comes thorough vividly. His efforts at abolition are not done solely for the enslaved, although they obviously are of primary concern, but he also sees that when freedom and liberty are achieved for all, that all actually benefit. When Douglass helped defeat slavery, and who could argue that he did not play a significant role with all of the speaking, writing, and recruiting, he moved to the next challenge. When citizenship was obtained with the 14th amendment, he moved to the next hurdle, voting rights, and when the 15th amendment passed, he continued to fight for the rights of the poor, women, and other marginalized people as the nation and racism evolved in the post-Civil War decades.

Another intriguing aspect that Bright brought to my attention was Douglass's politics. Although originally a proponent of the Liberty Party, and at first a reluctant supporter of the Republican Party, due largely to their initial support of colonization and lack of moral repugnance against slavery, Douglass eventually became a Republican stalwart. He viewed the 19th century Republicans as the agents of progressive change and the opposing force to Democratic conservatism. Douglass's disdain for Andrew Johnson and his stump support of men such as Grant, Hays, Garfield, and Harrison shows clearly his political leanings. Douglass was never afraid to wave the bloody shirt or remind Americans of his memory of what the Civil War was about or what resulted from it, and he never gave up fighting for better world until he drew his last breath in February 1895.

Lastly, although sometimes challenged by a lack of sources, Blight give us a better picture of Douglass's family relationships. Blight tries as much as possible to inform us about first wife Anna, who died in 1882, and second wife Helen Pitts, a 20-year younger white woman, who survived Douglass. He tells about the sibling rivalries among the great abolitionist's children and some of their challenging spouses. And he tells us about the women who worked for Douglass, such as German Ottilie Assing, who desired to be Mrs. Douglass, and editorial assistant Julia Griffith Crofts, who worked tirelessly in support of Douglass and abolitionism.

This is a masterpiece of biography. It is now the definitive work on America's foremost 19th century African American and it could not come a better time. Douglass's story of rising from enslavement to man of many prominent positions is one that is both educational and inspiring. I most highly recommend it!

I had read Douglass's three autobiographies, as well as the William McFeely biography, along with a host of other studies on Douglass over the last two decades, but none of them come close to the research, narration, and analysis that Blight provides. As one might imagine choosing what to put in and leave out about such an accomplished man's life can be quite the challenge, and although Blight uses over 750 pages to tell Douglass's amazing story, he crafts it in such a way that the abolitionist's life story melds seamlessly from one decade to the next and from one cause to the next.

What this book really made clear to me is that Douglass was a life-long fighter. Blight does a fantastic job of telling about Douglass's enslaved experience and how he developed almost an addiction to reading and learning as a boy. His transition from fugitive to abolitionist spokesperson and then move from Garrisonian moral suasion proponent to practical activist are explained so well by Blight. Douglass's life of struggle to better all humanity comes thorough vividly. His efforts at abolition are not done solely for the enslaved, although they obviously are of primary concern, but he also sees that when freedom and liberty are achieved for all, that all actually benefit. When Douglass helped defeat slavery, and who could argue that he did not play a significant role with all of the speaking, writing, and recruiting, he moved to the next challenge. When citizenship was obtained with the 14th amendment, he moved to the next hurdle, voting rights, and when the 15th amendment passed, he continued to fight for the rights of the poor, women, and other marginalized people as the nation and racism evolved in the post-Civil War decades.

Another intriguing aspect that Bright brought to my attention was Douglass's politics. Although originally a proponent of the Liberty Party, and at first a reluctant supporter of the Republican Party, due largely to their initial support of colonization and lack of moral repugnance against slavery, Douglass eventually became a Republican stalwart. He viewed the 19th century Republicans as the agents of progressive change and the opposing force to Democratic conservatism. Douglass's disdain for Andrew Johnson and his stump support of men such as Grant, Hays, Garfield, and Harrison shows clearly his political leanings. Douglass was never afraid to wave the bloody shirt or remind Americans of his memory of what the Civil War was about or what resulted from it, and he never gave up fighting for better world until he drew his last breath in February 1895.

Lastly, although sometimes challenged by a lack of sources, Blight give us a better picture of Douglass's family relationships. Blight tries as much as possible to inform us about first wife Anna, who died in 1882, and second wife Helen Pitts, a 20-year younger white woman, who survived Douglass. He tells about the sibling rivalries among the great abolitionist's children and some of their challenging spouses. And he tells us about the women who worked for Douglass, such as German Ottilie Assing, who desired to be Mrs. Douglass, and editorial assistant Julia Griffith Crofts, who worked tirelessly in support of Douglass and abolitionism.

This is a masterpiece of biography. It is now the definitive work on America's foremost 19th century African American and it could not come a better time. Douglass's story of rising from enslavement to man of many prominent positions is one that is both educational and inspiring. I most highly recommend it!

Saturday, December 22, 2018

Main Street Hospital for Slaves in Richmond

I've posted on here about a couple of hospitals that focused on treating slaves in the South. Those facilities were Jackson Street Hospital in Augusta, Georgia, and Dr. Robards Private Infirmary for Negroes in Memphis. This week while browsing through Virginia newspapers I located one in Richmond, Main Street Hospital. The above advertisement appeared in the Christmas Day 1860 issue of the Richmond Daily Dispatch.

With slaves being such a valuable commodity, it is no wonder that health care providers target marketed their services to owners who wished to keep their enslaved property healthy and productive. In Richmond, the second largest slave trade center in the South, a hospital for slaves, especially one near the epicenter of the trade at Shockoe Bottom, had to be seen by them as an attractive alternative to nurse ill slaves back to health for the market.

The ad claims that the hospital was for the "MEDICAL, SURGICAL and OBSTETRICAL treatment of SLAVES. The notice also provides the terms of treatment costs and listed the names of three medical doctors and the resident assistant. I assume names of the physicians were provided for reference purposes.

Friday, December 21, 2018

Nathan Sprague, 54th Massachusetts, Frederick Douglass's Son-In-Law

It is well known that Frederick Douglass, the noted black abolitionist, had two sons, Charles and Lewis, who served in the famous 54th Massachusetts Infantry. Another son, Frederick Jr., served as a recruiting agent in the Mississippi River Valley. However, it is not as widely known that son-in-law, Nathan Sprague fought in the 54th as well.

Unfortunately, not a whole lot of information is available in Pvt. Nathan Sprague's service records. Sprague married Rosetta Douglass, the abolitionist's oldest child, on Christmas Eve, 1863. He was born enslaved in Prince Georges County, Maryland, about 1841, but by the late 1850s he had settled in Rochester, New York, where he worked as a gardener.

Sprague's service records do tell us that he was 23 years old and eleven months when he enlisted in Company D of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry on September 3, 1864. The timing of Sprague's enlistment is interesting. He joined up after he was married, much later than his two brother-in-laws had signed up, and after his regiment's July 18, 1863 dramatic show of courage at Battery Wagner, made famous in the movie Glory. Perhaps Sprague was prompted into service by his wife, or felt pressure to join since his father-in-law's name appears (above) on his enlistment, or maybe he saw the service as an opportunity for career networking and future advancement. Maybe he just wanted to do his part in ending slavery and proving black men were as able to fight and thus entitled to equal citizenship rights as white men.

The young enlistee was listed as 5 feet 6.5 inches tall. His hair, eyes, and complexion, were all described as black. Sprague enlisted for one year and received 1/3 for his $100 bounty upon signing up. It appears that he mustered out on August 20, 1865, in Charleston, South Carolina.

After the war, Sprague returned to civilian life like so many other Union veterans and found the transition difficult. He bounced around from job to job, developed a stained relationship with his brother-in-laws, borrowed money often from his father-in-law, all while being defended by his wife. He and Rosetta eventually had seven children, six girls and a boy. Sprague died in Washington D.C. in 1907, and buried in Mount Hope Cemetery in Rochester.

Thursday, December 20, 2018

Frederick Douglass Fled

I mentioned in a recent post that I am currently reading David Blight's Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom. It is a fascinating read, bringing many aspects of Douglass's life that I was not that familiar with to light. One episode I did know a little something about was Douglass's exodus from the United States in the wake of John Brow's raid.

Curious to see if this news landed in Southern newspapers, and expecting it did, I wanted to see how it was told. I searched through several weeks of the Richmond Daily Dispatch following the Harper's Ferry affair, and in the October 27, 1859, issue I hit upon the small notice above.

Douglass, fearing implication in the raid and worrying about conspiracy charges due to some of Brown's papers captured following the failed mission, did indeed flee to Canada. This little article, with an attempt at tongue-in-cheek humor spun his flight to protect himself and the interests he had built u over the years into an "underground railroad" ride to Canada.

In truth, when Douglass became aware of Brown's attempt, the black abolitionist was in Philadelphia. On October 20, Douglass was escorted to Paterson, New Jersey and took the railroad home to Rochester, New York. He quickly packed his luggage and took a boat across Lake Ontario to Canadian soil.

In November 1859, Douglass moved through Toronto to Quebec, where he embarked to Liverpool, England on the Nova Scotia. This was Douglass' second trip to Great Britain. He spoke at various spots in England and Scotland during his sojourn. He returned home in late April 1860, but avoided the speaking limelight as the U.S Senate continued its Harper's Ferry raid investigations.

However, it was not only the Southern press who denigrated Douglass for his flight. Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, rival to Harper's Weekly, included a political cartoon in their November 12 issue showing a hurried Douglass losing one of his shoes and his hat while carrying a traveling trunk on his shoulder. The cartoon was titled, "The Way in Which Frederick Douglass Fights Wise of Virginia." As if a black man in post-Dred Scott America had a wink of a chance in any court of law!

Wednesday, December 19, 2018

Rescue of a Fugitive Slave

Incidences of fugitive rescues happened with increasing frequency in the decade after the passage of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law. The most well known rescues and rescue attempts were those that happened in eastern states, and thus seemed to get the most East Coast press. The cases of Shadrack Minkins, Anthony Burns, William Henry (Jerry rescue), among many others, are all rather well known by historians.

However, fugitive slave rescues happened all across the spectrum of northern states, as is shown in the news article above, published in the October 27, 1859 issue of the Richmond Daily Dispatch, and that happened in Ottawa, Illinois.

Cases such as this one brought added pressure to the already divisive issue of slavery. Northerners did not feel obligated to help maintain a labor system they did not feel they benefited from, and one that many felt was morally objectionable. Not that most Northerners believed in equality between whites and blacks, but most did not hold to the idea of a person owning another person. Southerners on the other hand believed that since the Fugitive Slave Law was a federal law, their northern neighbors were obligated to abide by it, whether they liked it or not. When secession came, most southern states included among their stated reasons for leaving the Union the North's unwillingness to uphold the law. Without slavery there would not have been secession, and without secession there would have been no war.

Tuesday, December 18, 2018

Dying Far From Home: Corp. John Jewell, 118th USCI

After viewing the World War I documentary, They Shall Not Grow Old, last evening, I feel a certain obligation to start writing some of these memorial posts again.

While I've shared United States Colored Troops soldiers' stories from Poplar Grove National Cemetery near Petersburg, and City Point National Cemetery at Hopewell in the past, it was about a week and a half ago, after showing a couple of friends around the New Market Heights battlefield, that I first visited Fort Harrison National Cemetery. Being that it is within relatively close proximity to New Market Heights, I thought I might be able to pay my respects to some of those men killed in that fight.

One of the interpretive waysides at the cemetery states that there are several New Market Heights causalities buried there. However, most of those with names on headstones do not seem to be associated with New Market Heights, but rather died in other ways, most in the final few months of the war. Perhaps a number of those unidentified (marked with small square blocks as pictured above) were killed at New Market Heights.

.

One of those men that lies in an identified grave is Corporal John Jewell of Company F, 118th United States Colored Infantry. Reviewing Jewell's service records, I found some interesting information.

John Jewell was born in Spencer County, Kentucky. He is described as 5 feet 6.5 inches tall, with a black complexion, black hair, and black eyes. Another service record card claimed he was "copper" complexioned. He was 21 years old when he enlisted at Owensboro, Kentucky, on September 27, 1864. His service records indicate that he was promoted to corporal the same day that he enlisted. The 118th officially mustered into service at Baltimore, Maryland, on October 19, 1864.

The 118th became part of the XVIII Corps in the Army of the James, first as part of a provisional brigade in the Third Division. They were then transferred to the all-black XXV Corps when it was created (First Brigade, Third Division). They remained on the Petersburg/Richmond front while other elements of the XXV Corps participated in the Fort Fisher Campaign in North Carolina.

Unfortunately, Jewell was killed in action during a fight at Fort Brady on the James River called the Battle of Trent's Reach on January 24, 1865. Fort Brady was constructed by the Union army after capturing Fort Harrison and New Market Heights in the fierce late September 1864 fighting. Fort Brady, being adjacent to the James River, was posted with heavy guns and helped keep Confederate gunboats north of that location on the James River.

Jewell's final personal effects are listed among his service records forms. They included:

1 forage cap

1 uniform coat

2 pair of trousers

1 pair of cotton drawers

2 flannel shirts

1 pair of shoes

1 pair of socks

1 pair of gloves

Jewell's personal effects were "turned over to his Brother Ben Jewell - being his legal heir." Pvt. Ben Jewell was also in Co. F. He was John's older brother, listed at 26 years old. Ben survived the war and mustered out in Texas in February 1866.

John and Ben's service records show that they were owned by David Jewell of Daviess County, Kentucky. David Jewell appears in the 1860 census as a 52 year old farmer, who owned $6,000 in real estate and $10,000 in personal property. The 1860 slave schedules show that David Jewell owned 9 enslaved men, women, and children, who ranged in age from 4 to 75. One, a 40 year old female, is noted as an "idiot." Two males of John and Ben's approximate age (21 and 23) are included on the list and are surely the two brothers.

Benjamin Jewell probably went back to Kentucky with a heavy heart after losing his brother during the war. Ben appears in the 1870 census in Daviess County as a 32 year old "farm hand" with $100 in personal property. In his household is his wife, Jane, daughters Mariah, and Martha, and son, 4 year old John William, most likely named for his uncle, born since the end of the war.

Rest in peace Corp. Jewell.

Monday, December 17, 2018

They Shall Not Grow Old

It's fairly obvious that my primary history interests do not stray too far from the United States, 1800-1880 time frame. However, tonight I had the great good fortune to see They Shall Not Grow Old at our local Regal Cinema.

Produced and directed by Peter Jackson of Lord of the Rings fame, this documentary is a fantastic accomplishment. Using BBC oral history interviews from British WWI veterans in the 1970s, and war film footage from the Imperial War Museum, Jackson provides the viewer with a great understanding of the UK's common soldiers.

What really struck me was the common threads of soldier experiences despite different times and different conflicts. In many of the interviews, other than changes in uniforms and weaponry, much of the day-to-day struggles of British WWI soldiers were quite similar to that of Union and Confederate soldiers of the American Civil War. Particularly poignant were the veterans' discussions of transitioning from solder life back to civilians, and how those at home had no idea of what combat entailed and how impossible it was to describe it to them.

After the film and credits are completed, Jackson spends about 30 minutes or so describing the making of the film, from doing the research, to getting the background sound correct, to colorizing the film, to lipreading the silent films, and so much more.

They Shall Not Grow Old is being shown again in selected theaters across the United States on December 27 at 4:00 pm and 7:00 pm. If it is shown near you and you have the time, I highly recommend seeing it. It is truly powerful.

Sunday, December 16, 2018

A Visit to a Hero's Grave - Vermont's Capt. Charles G. Gould

If you've ever been to Pamplin Historical Park and the National Museum of the Civil War Soldier, and then made the short walk to the Park's Battlefield Center, you likely encountered the dramatic story of Captain Charles Gilbert Gould.

Gould enlisted in the 1st Vermont Heavy Artillery in the fall of 1862 and remained in garrison duty for much of the war until he received a promotion to captain of Co. H in the 5th Vermont on December 30, 1864.

Soon after his promotion Gould sought and received a 20-day furlough to go home. In his service records is a copy of the letter he penned ostensibly to visit his home in Windham, Vermont and help settle the estate of his deceased father. His request was approved (see below).

The only problem with Gould's request is that it seems it was made under false pretenses. Sixteen year old Charles Gould appears in his father, James's, household in the 1860 census with mother Judith and older brothers Aaron (24) and James M. (17). Father James was 47. Checking the 1870 census, James still appears at age 57 with his wife Judith, but now the couple had an empty nest. James was not dead when Charles made his request.

Regardless of his alleged fib to gain a furlough, the not yet 20 year-old Gould stepped up when it came time to exhibit bravery. Below is a quote stating the distinctive part Gould played and that was later printed the May 2, 1865 issue of the the nearby Manchester (Vermont) Journal. The paper reprinted the official after action report from the April 2, 1865 Breakthrough at Petersburg.

Gould received a brevet promotion to major for his bravery. And an even higher honor, the Congressional Medal of Honor in 1890 for his heroic actions 25 years earlier at Petersburg.

Back in November, while on our honeymoon in Vermont, we stayed in Manchester. Looking up Windham on the map, we found it was only a short drive up into the Green Mountains to the small isolated community. My wonderful wife and I decided to take a few minutes to go visit the hero's grave and pay our respects. It was a cold and windy day, and it took some searching once at the cemetery, but we found him (pictured top), resting in peace nestled in his beloved Green Mountains and among a number of other Vermont Civil War veterans.

Saturday, December 15, 2018

Recent Acquisitions to My Library

My birthday landed on Thanksgiving this year, and thanks to my wonderful wife, I received Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom by David Blight as one of my gifts. For me, this was probably the most anticipated biographical release since James I. Robertson's Stonewall Jackson: The Man, the Soldier, the Legend. I was looking forward to reading Blight's new book so much that I jumped several others patiently waiting for my attention and started it this past week. What makes this book so anticipated you ask? Well, first of all, the subject of the study is arguably one of the most influential Americans of the 19th century. Secondly, David Blight is one of our country's most insightful and well written historians. Combine the significance of the subject and the quality of the author and you have the potential for a "once in a decade" book. I am thoroughly enjoying it, although I am only about 150 pages in. Of course, I'll be sharing a brief review when I finish it.

Speaking of anticipated books . . . Unfortunately, there have not been many Civil War common soldier studies in recent years. Yes, there has been a plethora of published letter collections from the perspective of the common soldier, but new studies that synthesize information and offer new angles that help us better understand the trials, and tribulations, and how men coped are sorely lacking. Coming to fill the void in common soldier studies is Peter Carmichael's The War for the Common Soldier: How Men Thought, Fought, and Survived in Civil War Armies. I heard Carmichael speak on this subject this past June at Gettysburg College's Civil War Institute. If you've not watched that talk, you should. And once you do, I bet you'll be buying this book, too.

I've long been a proponent of the argument that fugitive slaves' agency led directly to the Southern slave states seceding in 1860 and 1861, and thus prompted the outbreak of the Civil War. Most of my study on this subject has been focused in the decades form the 1830s to the 1860s. The War Before the War: Fugitive Slaves and the Struggle for America's Soul from the Revolution to the Civil War by Andrew Delbanco, however, promises to fill in the gaps of my knowledge from the end of the 18th century, and its 1793 Fugitive Slave Law, on into the first part of the 19th century.

My recent trip to Vermont has spurred a new interest in that state's participation in the Civil War. In my various readings about the Army of the Potomac, I've come across numerous references and quotes from Private Wilbur Fisk of the 2nd Vermont Infantry Regiment. Hard Marching Every Day: The Civil War Letters of Private Wilbur Fisk, 1861-1865, seems to offer the Civil War student an almost unprecedented portrait of soldier life in the Union army of the eastern theater.

James C. Klotter's Henry Clay: The Man Who Would Be President is another book that I've had on my wishlist for a while and that I received for my recent birthday. I had the good fortune to work with Dr. Klotter on a couple of different projects while I was at the Kentucky Historical Society. He is the consummate gentleman and historian. In this new work, Klotter seeks to explain how Clay never became president despite being immensely popular, charismatic, and politically accomplished. Despite being nominated and receiving electoral votes in three elections, and desired the Whig Party's nomination twice more; and despite being one of our nation's most gifted orators and top senators in history, he never attained the nation's highest political office. I'm looking forward to getting Klotter's explanation on all of this.

With the recent publication of Chandra Manning's Troubled Refuge: Struggling for Freedom in the Civil War, and now, Amy Murrell Taylor's Embattled Freedom: Journeys through the Civil War's Slave Refugee Camps, the so-called contraband camps of the Civil War are receiving some much needed scholarly attention. Taylor's essay on Camp Nelson, Kentucky, which appeared in Weirding the War: Stories from the Civil War's Ragged Edges, brought an important but largely forgotten story to light that influenced future legislation which saw Congress grant freedom to the immediate family members of formerly enslaved soldiers in the Union army. This book promises to similarly show how individuals who had practically no political power somehow influenced significant decisions that altered America forever. I'm interested in learning more about their individual stories and gaining inspiration from the decisions they made and the risks they took to gain freedom and fight for equality.

Thursday, December 13, 2018

LOST - My Free Papers

When I come across these types of advertisements while browsing historic newspapers I always try to share them, because they tell important stories. Individuals such as George Valentine, Mary Brown, Richard Newsome, and here Margaret James, all misplaced their certificates of freedom and likely fretted over their return. Most of them offered rewards for the safe return of the precious documents.

This particular advertisement ran in the Richmond Enquirer on October 4, 1864. I'm always curious to find out more about these individuals from available census records. In this case, however, it is a bit more difficult.

Much like Mary Brown, above, Margaret James, being such a common name, produces at least two possibilities in the 1860 census. Interestingly, they both lived in Richmond's Second Ward and were born within about five years of each other.

One Margaret James, a 24 years old domestic, lived in the household of Robert and Ellen James, likely her parents. Robert was listed as a "driver," probably meaning a wagon driver. All of the James family (2 sisters and a brother) are listed as mulatto and were all born in Virginia.

The other Margaret James, 19 years old with the occupation of "servant," lived in the household of Benjamin Davis, a white man, who was born in England and is listed as a "trader." Yes, Benjamin Davis was a slave trader. Margaret was noted as black. Interestingly, another African American woman, a mulatto, Alice Maning, 13 years old, and also listed as a "servant," lived in the Davis household, too. Both James and Maning were born in Virginia.

Being that he was a slave trader with seeming access to any type of laborer he could want, it seems somewhat curious that Davis would employ two free black women as servants rather than use enslaved individuals. Davis also appears in the 1860 slave schedules as the owner of five slaves. They consisted of one 40 year old mulatto male and four black females ages 30, 35, 19, and 60. Perhaps Davis believed he was able to be more profitable selling slaves and employing free women. Yet another conundrum of the "peculiar institution."

Wednesday, December 12, 2018

Just Finished Reading - Hood's Texas Brigade

During (and following) the Civil War, some regiments and brigades achieved legendary status. The Stonewall Brigade, the Iron Brigade, the Irish Brigade, and certainly Hood's Texas Brigade, among a few others, stand out for their fighting ability.

In Hood's Texas Brigade: The Soldiers and Families of the Confederacy's Most Celebrated Unit, author Susannah J. Ural examines these westerners who fought primarily in Gen. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia to try to explain why they were so extraordinary. Ural is able to credit the Texans' effectiveness to several factors.

First, from early on, the brigade identified themselves with the Confederate cause. Most of the men (or their parents) and their families had moved to Texas as the United States was expanding. Many had benefited from the institution of slavery and the success it brought them socioeconomically through agricultural pursuits. When war came in 1861 with the secession of the Lone Star State, a rush to arms filled the ranks of what would be the core of the Texas Brigade (1st, 4th, 5th infantry regiments).

Secondly, there was a strong bond between the officers and enlisted men in the brigade. Several attempts were made to install officers in regiments against the enlisted men's wishes, which created difficult situations and several officers' resignations. Once acceptable officers were placed, unit morale soared. The officers took care of the men as best they could and the men fought as as hard as they could for their officers.

Thirdly, the men demonstrated a commitment to a growing reputation and showing that Texans were the best troops in the Army of Northern Virginia. Instead of staying in the Trans-Mississippi or Western Theater, these Texans believed that the war would be fought and won in Virginia and desired to be where they could make the greatest impact.

And fourthly, the Texans had a tremendous support structure back home. The soldiers' families back on the plains, plantations, and pine woods of East Texas were as committed as the soldiers themselves to attaining Confederate independence.

That final point is where this book, in my opinion, surpasses several other unit histories. As the subtitle suggests, Ural takes time to tell the stories of the soldiers' families on the home front and how their encouragement sustained the men in the most difficult times. Through high battle casualties, disease, and periodic supply shortages, the solders could always rely on the home folks. This support system contributed toward reduced desertion figures for the Texans as compared to many other units.

Hood's Texas Brigade provides historians with an excellent example of how unit history should be written. Getting to know the Texas Brigade inside and out helps us better understand why so many Confederates went to such great lengths in their efforts for independence. I highly recommend it.

Tuesday, December 11, 2018

Enormous Price

Perusing Civil War newspapers in effort to catch bits of military information almost always turns up peripheral social, economic, and political information if one keeps their eyes open for it.

While reading Hood's Texas Brigade by Susannah J. Ural, I learned that some of the Texans posted an advertisement in the Richmond Whig seeking shoes for their soldiers. Not having access to digital versions of the Whig, I wondered if they might have posted the advertisement in other Richmond papers. I looked through some of the available November 1863 issues of the Richmond Enquirer, but got sidetracked by many of the advertisements that mentioned slavery in the November 3 edition. One brief notice (pictured above) particularly caught my eye.

After the introductory title "ENORMOUS PRICE.-" it reads: "A negro girl, aged seventeen, was sold by Hargrove & Co. for the small fortune of six thousand one hundred and fifty dollars cash, on Monday last, at Lynchburg."

My historical thinking mind started churning. The first thing that came to me, largely from my reading and research on slavery was that this was likely a "fancy girl" situation. Especially attractive, young, female slaves sometimes brought extraordinary prices. Although the advertisement does not give a physical description of this young woman, those of light complexion, straight hair, and shapely form sometimes became the most sought after of possessions. Desired by both slave traders, who hoped to improve profits on their human investments, and often bachelor males who sought enslaved females for sexual purposes, bidding wars sometimes drove prices to astounding amounts.

Attempting to consider all possibilities, and thus continuing my line of thinking led me to reason that war-time inflation may also have escalated slave prices. Inflation had repercussions on almost everything in the Confederacy, particularly items in short supply. However, it seems that if inflation was the cause, this would not have been an outstanding case and thus the newspaper would not have claimed it an "enormous price."

Enslaved people who possessed skills often brought higher prices. Coopers, carpenters, brick masons, weavers, cooks, and similarly skilled laborers commanded advanced values. But, those talents normally upped their cost by tens and hundreds of dollars, not normally the thousands of dollars that this young woman apparently commanded. It is difficult to believe that a seventeen year old woman had acquired many skills to bring such an exorbitant price.

Are there many other possibilities than this being a fancy girl? Does anyone have thoughts?

Monday, December 10, 2018

Albert Boisseau Home Burned

One never knows what one will find while browsing through old newspapers. Today, while looking through old issues of the Richmond Enquirer via an online platform, I happened on a report "FROM PETERSBURG" in the Friday, October 7, 1864 edition. In it are mentioned some activities related to the Battle of Peebles Farm, which occurred as part of Gen. Grant's Fifth Offensive at Petersburg (Sept. 30-Oct.2, 1864).

During the fighting, which ranged over a few miles, the Union army's V and IX Corps pushed back the Confederates and established a new line of earthen fortifications just a couple of stones throws south of where Pamplin Historical Park is today.

Part of the property where this action occurred was owned by Dr. Albert Boisseau, son of Tudor Hall plantation patriarch, William E. Boisseau, and brother of Tudor Hall's war-time owner, Joseph G. Boisseau. During the engagement, Dr. Boisseau's home happened to be between the lines and was probably used as cover for sharpshooters/skirmishers on both sides as the battle raged back and forth.

According to this article, Dr. Boisseau's house was burned on Tuesday, October 4, during "several small skirmishes" that occurred after the main fighting had ended. I had always assumed that it was burned during the days of the main battle. It is also interesting, but not particularly surprising, that the report states that the home was vandalized before it was burned. Houses and outbuildings were often dismantled for materials used to erect fortifications, and or winter quarters.

I will be looking for other pieces of evidence to corroborate this particular report, but I have no reason to doubt its validity at this point.

Saturday, December 1, 2018

Just Finished Reading - Calculating the Value of the Union

Much of the historical debate over slavery's divisiveness rests on whether the institution would be accepted or prohibited in the future western territories. Whether slavery would be allowed into the expanding west certainly brought its fair share of political debate on the issue in the years leading up to the Civil War. Others have argued that the main issue splitting the North and the South was the free states' unwillingness to abide by the Fugitive Slave Law and their passage of personal liberty laws, in effect nullifying the federal provision. This additionally strong argument is supported by a ton of evidence running through the 1840s, 1850s, and the claims made by the seceding states in their secession ordinances.

In Calculating the Value of the Union: Slavery, Property Rights, and the Economic Origins of the Civil War by James L. Huston offers a somewhat supplemental argument. Huston contends that both of the previously mentioned issues were instrumental, but they were couched within the overarching problem of property rights.

Since even before establishing the United States government through the Constitution Southerners had claimed property rights in slaves. The North, after the Revolutionary War made a move away from slavery and toward a free, wage-based labor system. Northerners also struggled accepting the idea of owning property in people. Racism was still pervasive in the North and most did not accept blacks as equals there but they believed that one man owning another reduced the value of labor and created unfair advantages by slaveholders.

This fear of allowing slavery into the western territories produced the rise of the Republican Party, which was opposed to further extension of the institution. As the 1850s wound down, Southerners, who believed that slavery was their best means toward future prosperity, were unwilling to make any compromise on losing or reducing the $3 billion in what they believed was legitimate property. When Republican Party candidate Abraham Lincoln was elected, Southerners felt their property rights were under assault and believed their only recourse was secession with South Carolina starting the tumbling Dominoes.

Huston mounts a solid argument based on good evidence, and while most sections of the book are clear, others get quite dense. I recommend it especially to those with political and economic niche interests.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)