Sunday, December 31, 2017

Happy New Year's Eve!

I would like to wish everyone a very Happy New Year. As we finish up the old year and ring in the new one, I want to thank you for your continued readership. It is my greatest hope that something that I wrote this past year resonated with you, created some curiosity to learn something new, or made you think about a historical event, person, or issue in a different way.

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress. Auld Lang Syne Cigars advertisement, 1871.

Saturday, December 30, 2017

"The Black Regiment" by George H. Boker

I found this poem on the same Library of Congress document that contained the Andrew Johnson and Emancipation in Maryland stories that I shared at the end of November and early this month. I had not read this one before and thought it might be new to others as well, so here you go.

The poem was composed by George H. Boker, a leading poet and playwright of the day.

The poem was composed by George H. Boker, a leading poet and playwright of the day.

Friday, December 29, 2017

Recent Acquisitions to My Library

This Christmas season brought with it a several opportunities to expand my library. Some of my recent acquisitions were books that I received as direct gifts or from gift card purchases, one was for a book review, and one is a selection that that I had on my Amazon.com Wishlist that I bought for myself when I saw the price had dropped.

Released just last October, Ron Chernow's Grant is receiving rave reviews. I've seen the author interviewed on a number of popular talk and morning television shows, so hopefully it sparks an interest with the larger population and creates a buzz much like his earlier book on Alexander Hamilton did. However, I don't know if Grant is the material to make into a hip-hop musical, but hey, who knows? Grant runs almost 1000 pages, so it may be a while before I commit to starting it, although I have heard it is a true page-turner.

Anytime something comes out on Nat Turner, I eventually have to read it. That historical event is one of those that particularly fascinates me. I'm excited to read the interpretive approach that David Allmendinger, Jr. puts forth in Nat Turner and the Rising in Southampton County and see what new evidence he finds to make this book different from several others that have been published in the last decade or so.

Another topic that is finally receiving more and more scholarly attention is Civil War guerrilla warfare. One of the emerging historians in this field is Matthew Hulbert. His book The Ghosts of Guerrilla Warfare: How Civil War Bushwhackers became Gunslingers in the American West was published in October 2016 by the University of Georgia Press, and has received excellent reviews in a number of scholarly journals. This book seeks to show how Civil War era guerrillas have been remembered and portrayed since the conflict.

Tera W. Hunter's Bound in Wedlock: Slave and Free Black Marriage in the Nineteenth Century, promises to be a social history triumph. Nineteenth century white Americans, who most often viewed African Americans as non-citizens politically, and inferiors socially, also often viewed black marriage as less recognizable than their own. Enslaved, and even free blacks, who had little to no legal standing sometimes saw themselves separated from their partners on the will or whim of those who held power. I am interested in learning more about how blacks themselves viewed their marriages and I'm also hopeful a number of the historical myths surrounding slave ceremonies will be covered.

A Union Indivisible: Secession and Politics of Slavery in the Border South by Michael D. Robinson is another work that I had on my Amazon.com Wishlist. However, the literary gods must have smiled on me, because I was soon blessed by receiving it in exchange for writing a book review for it. Border state studies have really ramped up in the last eight years or so. And A Union Indivisible looks to be a fine addition to this particular field along with studies from William C. Harris, Aaron Astor, Christopher Phillips, Anne Marshall, Patrick Lewis, Matthew Stanley, and Brian McKnight, among others. I remember first hearing about this work while dining with William J. Cooper, Jr., who was the keynote speaker at the Kentucky History Education Conference a few years back. He mentioned he had a graduate student named Michael Robinson who was working on a dissertation on the border states. I had been keeping my eyes and ears open for its publication since that time, as Cooper gave his student such high praise for his writing and research. I'm looking forward to reading it and continuing to expand my knowledge of the border states during the Civil War era.

Wednesday, December 27, 2017

Books I Read in 2017

As the December days disappear, it looks like I will not finish another book this year. Therefore, I will post the list of ones I have completed over the last twelve months. I often share the current book I am reading on my Facebook page, and then when finished, I write a brief summary paragraph of it to hopefully spark some curiosity in friends with similar reading interests. However, I've never listed the books that I read in a given year.

I've been keeping a list of books I read since the beginning of 2006. I don't know what a psychiatrist might think if I told him or her that about me, but it has come in handy at times when I've wanted to confirm that I had already read a particular book. Anyway, here goes. Oh, I've highlighted a few of these that I found especially insightful, helpful, or just plain fascinating.

1. Writing the Civil War: The Quest to Understand. Edited by James M. McPherson and William J. Cooper

2. Liberty, Virtue and Progress: Northerners and their War for the Union by Earl J. Hess

3. Slavery and Forced Migration in the Antebellum South by Damian Alan Pargas

4. The Roots of Southern Distinctiveness: Tobacco and Society in Danville, Virginia, 1785-1865 by Frederick F. Siegel

5. Counterfeit Gentlemen: Manhood and Humor in the Old South by John Mayfield

6. Troubled Refuge: Struggling for Freedom in the Civil War by Chandra Manning

7. Slave Life in Virginia and Kentucky: A Narrative by Frances Frederick, Escaped Slave. Edited by C.L. Innes

8. The Peninsula Campaign and the Necessity of Emancipation: African Americans and the Fight for Freedom by Glenn David Basher

9. Dueling in the Old South: Vignettes of Social History by Jack K. Williams

10. The Making of a Racist: A Southerner Reflects on Family, History, and the Slave Trade by Charles B. Dew

11. Reminiscences of Life in Camp by Susie King Taylor

12. River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in the Cotton Kingdom by Walter Johnson

13. Virginia's Private War: Feeding Body and Soul in the Confederacy, 181-1865 by William Blair

14. The Rebel Yell: A Cultural History by Craig A. Warren

15. Landon Carter's Uneasy Kingdom: Revolution and Rebellion on a Virginia Plantation by Rhys Isaac

16. Creek Paths and Federal Roads: Indians, Settlers, and Slaves and the Making of the American South by Angela Hudson

17. The Peace that Almost Was: The 1861 Washington Peace Conference and the Final Attempt to Avert Civil War by Mark Tooley

18. Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862-1867 by William A. Dobak

19. Fort Harrison and the Battle of Chaffin's Farm: To Surprise and Capture Richmond by Douglas Crenshaw

20. Richmond Must Fall: The Richmond-Petersburg Campaign, October 1864 by Hampton Newsome

21. The Guerrilla Hunters: Irregular Conflicts during the Civil War. Edited by Brian D. McKnight and Barton A. Myers

22. The First Battle for Petersburg: Attack and Defense of the Cockade City, June 9, 1864 by William Glenn Robertson

23. Thunder at the Gates: The Black Civil War Regiments that Redeemed America by Douglas R. Edgerton

24. John Randolph of Roanoke by David Johnson

25. Lincoln and the U.S. Colored Troops by John David Smith

26. The Bloody Crucible of Courage: Fighting Methods and Combat Experience of the Civil War by Brent Nosworthy

27. To Have and to Hold: Slave Work and Family Life in Antebellum South Carolina by Larry E. Hudson, Jr.

28. We Look Like Men of War by William R. Forstchen

29. Gender and the Sectional Conflict by Nina Silber

30. The Yankee Plague: Escaped Union Prisoners and the Collapse of the Confederacy by Lorien Foote

31. The Making of a Confederate: Walter Lenoir's Civil War by William L. Barney

32. A Troublesome Commerce: The Transformation of the Interstate Slave Trade by Robert H. Gudmestad

33. The Army of the Potomac in the Overland and Petersburg Campaigns: Union Soldiers and Trench Warfare, 1864-1865 by Steven Sodergren

34. William Lowndes Yancey and the Coming of the Civil War by Eric H. Walther

35. South Carolina Fire-Eater: Laurence M. Keitt, 1824-1864 by Holt Merchant

36. Ku Klux: The Birth of the Klan during Reconstruction by Elaine Frantz Parsons

37. The Price for Their Pound of Flesh: The Value of the Enslaved, from Womb to Grave, in the Building of a Nation by Daina Ramey Berry

38. Northerners at War: Reflections on the Civil War Home Front by J. Matthew Gallman

39. The Imperfect Revolution: Anthony Burns an the Landscape of Race in Antebellum America by Gordon S. Barker

40. An Irishman in Dixie: Thomas Conolly's Diary of the Fall of the Confederacy. Edited by Nelson Lankford

41. The Field of Honor: Essays on Southern Character and American Identity. Edited by John Mayfield and Todd Hagstette

42. The Judas Field: A Novel of the Civil War by Howard Bahr

43. The Battle of New Market Heights: Freedom Will be Theirs by the Sword by James S. Price

44. Our Good and Faithful Servant: James Moore Wayne and Georgia Unionism by Joel McMahon

45. Storm Over Texas: The Annexation Controversy and the Road to Civil War by Joel H. Silbey

46. Drift Toward Disunion: The Virginia Slavery Debate of 1831-1832 by Alison Goodyear Freehling

47. Uncommon Valor: A Story of Race, Patriotism, and Glory in the Final Battles of the Civil War by Melvin Claxton and Mark Puls

48. Eagles on Their Buttons: A Black Infantry Regiment in the Civil War by Versalle F. Washington

50. American Scoundrel: The Life of the Notorious Civil War General Dan Sickles by Thomas Keneally

51. The Secret Life of Bacon Tait: A White Slave Trader Married to a Free Woman of Color by Hank Trent

52. War Upon Our Border: Two Ohio Valley Communities Navigate the Civil War by Stephen Rockenbach

53. On to Petersburg: Grant and Lee, June 4-15, 1864 by Gordon Rhea

54. America's Forgotten Caste: Free Blacks in Antebellum Virginia and North Carolina by Rodney Barfield

55. Midnight in America: Darkness, Sleep, and Dreams during the Civil War by Jonathan W. White

56. Freedom's Dawn: The Last Days of John Brown in Virginia by Louis A, DeCaro, Jr.

57. Civil War Citizens: Race, Ethnicity, and Identity in America's Bloodiest Conflict. Edited by Susannah J. Urals

58. Sojourner Truth: A Life, A Symbol by Nell Irvin Painter

59. There is Something About Edgefield: Shining a Light on the Black Community through History, Genealogy, and Genetic DNA by Edna Gail Bush and Natonne Elaine Kemp

60. The Worst Hard Time: The Untold Story of Those Who Survived the Great American Dust Bowl by Timothy Egan

61. Something Must Be Done About Prince Edward County: A Family, a Virginia Town, a Civil Rights Battle by Kristin Green

So there you go! Sixty-one books in fifty-two weeks. Not too bad. I feel thankful that my life situation allows me such ready access to books, and the time to read them. Like Thomas Jefferson once said, "I cannot live without books!"

Tuesday, December 19, 2017

Just Finished Reading - There Is Something About Edgefield

It has been quite a while since I've posted a book review on this forum. I've written a number of reviews for other publications in 2017, so that, perhaps unfairly, has resulted in a diminished number here. However, I recently received an opportunity to review There Is Something About Edgefield: Shining a Light on the Black Community through History, Genealogy, and Genetic Testing by Edna Gail Bush and Natonne Elaine Kemp (Rocky Pond Press, 2017) and jumped at the chance.

Ever since I read All God's Children: The Bosket Family and the American Tradition of Violence by Fox Butterfield, about twenty years ago, I've sought to learn more about Edgefield County when an opportunity presented itself. Located along the Georgia border in west-central South Carolina, the area produced some of the state's most noted politicians and fierce defenders of slavery and post-Civil War white supremacy. Born in Edgefield were governors George McDuffie, Pierce Mason Butler, James Henry "Cotton is King" Hammond, Francis W. Pickens, Benjamin "Pitchfork" Tillman, and Strom Thurmond. Edgefield also produced Preston Brooks (who caned Charles Sumner on the Senate floor in 1856), and Confederate general James Longstreet.

As one might imagine, Edgefield County had a large enslaved population, and the authors' attempts to connect to their Edgefield ancestors is the main focus of the book. In 1860, there were over 24,000 slaves in the county. This is the sixth highest total in the United States that year!

There Is Something About Edgefield begins with thoughtful and informative sections which provide the co-authors' acknowledgements, as well as a preface, forward, and introduction.

Co-author Edna Gail Bush supplies the first two chapters of the book. In the first chapter Bush examines her paternal ancestors and focuses on the family's ability to acquire land in post-Civil War Edgefield, and sadly, how it was eventually taken from them. Bush also shares the amazing story of her DNA findings. She had her brothers take the Y-DNA tests and found that the results indicated her paternal line as originating solely from European countries. As she states, "The fact is, for many African Americans, a European progenitor serves as the original head of the paternal line." (pg. 55)

In the second chapter, Bush seeks and provides information on her maternal ancestors. Doing genealogical research for African American ancestors is difficult enough, especially when searching before 1870, but finding maternal lines lend extra special challenges. Her search for information found an early date of about 1799 for one ancestor and also put her on the trail of her maternal ancestors' enslavers, the Burton Family. As Bush wisely writes "It is a sad fact that the only way I have been able to trace my enslaved ancestors is by looking through records that pertain to property, which may or may not even give the dignity of a name." (Pg. 80). After emancipation in 1865, things do not always get easier for the genealogist. Although census information is available for African Americans from 1870 on, there are still obstacles such as name changes, gaps here and there due to census taker errors, and often overlooked households or households with incorrect information.

Natonne Elaine Kemp examines the line of her Blair ancestors in chapter three. In doing so Kemp reminds us that networking with other researchers can be of great benefit. Sharing one's findings, discussing them with others, and receiving help with research obstacles is one of the most rewarding aspects of doing historical research. This chapter is infused with contextual history, which I sincerely appreciated. In telling about her ancestor's challenges, especially during the Reconstruction years, Kemp exposes the terroristic state in which Edgefield's black population found itself after the Civil War, when recently defeated whites sought to reclaim political dominance through intimidation, mayhem, and murder.

Kemp continues searching for her Blair connections in chapter four, but puts particular emphasis on an incident where a white Blair killed an African American man in 1872. The examination of this particular incident illustrates the significant knowledge one acquires during the research process. It is one thing to read about Reconstruction violence from a formal history book, it is yet another to get into the nitty-gritty of a specific tragic occasion, which in turn illustrates the larger situation. I also found Kemp's research on Calliham Baptist Church intriguing. The break from the church by its black members after the Civil War and the Calliham congregation's response is particularly fascinating.

The also book contains three short epilogues. The first provides a bullet-point list that enumerates post-1870 potential sources for information on African American genealogy. The second and third reemphasize the help that DNA testing can provide, particularly when searching a specific geographic area.

I was especially impressed with the book's documentation. Being a historian, it is pleasing to see a work so clearly cited. It adds a level of credibility that can only come through such work. Other pluses to the book were the included family photographs. Seeing the people who where being researched and written about adds a level of connection to their stories that words alone cannot fill. In addition, the defined terms related to DNA testing were helpful to someone who is not all that familiar with this rather new form of research. Lineage charts, maps, graphs, and other primary sources were all selected with care and only enhance the book's many strengths.

One might think that a book on someone else's genealogy could not be a "can't put down" type of book, but I found that There Is Something About Edgefield is one of those kind of books. It is not only a family tree book. Rather, by describing their exhaustive research resources, both traditional and non traditional, the authors give readers ideas on the plethora of ancestral information sources available to family history researchers. But not only that, this book gives hope. Hope for those searching to know their family's hidden pasts, and hope that through studying the past, we can create better presents and futures for all of us. By this point you can understand why I highly recommend this book. On a one to five scale, I have no reservations giving it an empathetic five! Well done!

Sunday, December 17, 2017

Sojourner Truth's Grandson, 54th Massachusetts POW

The 54th Massachusetts Infantry, a black regiment allowed to retain its state regimental designation, was composed of African American men from all across the free states. Some men were former slaves who had made new lives in the North, but many more were free men of color. In the regiment were the sons, grandsons, and relatives of black abolitionists. Famously, Frederick Douglass's two sons, Louis and Charles, served in the famous 54th, as did Martin R. Delaney's son, Touissant L'Overture Delaney. Another descendant of a black abolitionist in the 54th was James Caldwell (shown above), the grandson of Sojourner Truth. The image of Truth below shows Caldwell's photograph on her lap.

Caldwell appears in the 1860 census in Battle Creek, Calhoun County, Michigan as a sixteen year old, who was born in New York state. He is listed as "B" for black and appears in the household of Luther Slater, a fifty-seven year old white man, who was a blacksmith. This fits with his Civil War service records, which lists Caldwell's occupation as blacksmith. The young man was likely apprenticing with Slater before the war. Caldwell is the only non-white in the household.

I've tried to determine which child of Truth's was Caldwell's mother. It appears that it was Elizabeth. James may be one of those individuals who was counted twice in the 1860 census. In Sojourner Truth's household in Calhoun County, Michigan was Elizabeth Banks, who was thirty-three, and a James Colvin, which may have been a census takers mishearing of Caldwell, who is listed as fourteen years old, and born in New York state.

When he found out that the Union army was accepting black men, Caldwell apparently told to his famous relative, "Now is our time Grandmother to prove that we are men." Caldwell enlisted in Company H, 54th Massachusetts Infantry on April 17, 1863, and was mustered in on May 13 at Readville, Massachusetts, where the 54th trained. His records state he was nineteen when he enlisted and was five feet nine inches tall, with a "dark" complexion.

Caldwell's active service was rather short lived, as he was captured in an engagement on July 16, 1863, at James Island, South Carolina, just two days before the 54th attained their Glory at the Fort Wagner fight on Morris Island. It appears that Caldwell was held in Confederate hands for the almost two next years. His records indicate that he was finally released at Goldsboro, North Carolina, on March 4, 1865. His records also show that he spent at least part of this prisoner of war time at Florence, South Carolina, in the "rebel prison pen" there.

James Caldwell was sent on to Annapolis, Maryland (Camp Parole) for recovery. There he received his discharge on May 12, 1865, and received three months extra pay "due to hardships endured at Rebel prisons" by order of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton.

I was not able to determine what happened to young James Caldwell in the years following the Civil War. If anyone should happen to know or can point me in a direction to where I could find out, I would be grateful.

Image of James Caldwell in the public domain.

Image of Sojourner Truth courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Thursday, December 14, 2017

Sojourner Truth, Lyricist

I've been reading Nell Irvin Painter's Sojourner Truth: A Life, A Symbol over the last few days. It is certainly a fascinating biography. I was quite aware that Truth, a former Northern (New York State) slave, became a spokesperson for women's rights and abolition in the years before and during the Civil War. But I did not know that the illiterate activist, who dictated her life's narrative to a white writer, also composed lyrics to a song about African American soldiers that was sung to the tune of "John Brown's Body," or later, the "Battle Hymn of the Republic."

One might be inclined to think that an illiterate woman would not be able to come up with such touching verses, but they are indeed outstanding. The song was written in honor of the First Michigan Colored Infantry Regiment, which eventually was redesignated the 102nd United States Colored Infantry. The stirring words to the song are:

We are the valiant soldiers who've 'listed for the war;

We are fighting for the Union, we are fighting for the law;

We can shoot a rebel farther than a white man ever saw,

As we go marching on.

Chorus.-

Glory, glory, hallelujah! Glory, glory, hallelujah!

Glory, glory, hallelujah! as we go marching on.

Look there above the center, where the flag is waving bright;

We are going out of slavery, we are bound for freedom's light;

We mean to show Jeff Davis how the Africans can fight,

As we go marching on. - Chorus.

We are done with hoeing cotton, we are done with hoeing corn;

We are colored Yankee soldiers as sure as you are born.

When massa hears us shouting, he will think 'tis Gabriel's horn,

As we go marching on. - Chorus.

They will have to pay us wages, the wages of their sin;

They will have to bow their foreheads to their colored kith and kin;

They will have to give us house-room, or the roof will tumble in,

As we go marching on. - Chorus.

We hear the proclamation massa, hush it as you will;

The birds will sing it to us, hopping on the cotton hill;

The possum up the gum tree couldn't keep it still,

As he went climbing on. - Chorus.

Father Abraham has spoken, and the message has been sent;

The prison doors have opened, and out the prisoners went

To join the sable army of African descent,

As we go marching on. - Chorus.

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Wednesday, December 6, 2017

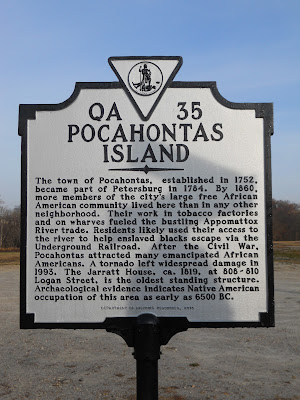

Pocahontas and Petersburg

On Monday I made an early morning trip to get my oil changed and tires rotated. While at the mechanic shop, I passed the time by reading, but fortunately it didn't take near as long as I expected. So on the way home I decided to stop by Pocahontas and see the new historical marker (below) a reader of this blog recently made me aware of. I won't go into a long history of this Appomattox River community, but I will encourage you to dig a little deeper than what is relayed on the above marker.

Pocahontas was the home to what many believe to be one of Virginia's, and the nation's, oldest free black communities. A wave of manumissions in Virginia followed the Revolutionary War and its spirit of liberty. These emancipations added numerous families to those free people of color who had been calling Pocahontas home for generations. Many of these people made their livings on the Appomattox River and by providing valuable services and skilled work to the commercial marketplace in adjacent Petersburg.

One time Pocahontas resident, Charles Stewart, became a noted jockey, riding for his master, William Ransom Johnson, who was one of the best-known turfmen in the Old Dominion. Stewart is shown in the above painting by noted equine artist Edward Troye, holding Johnson's horse, Medley.

The Jarratt House (above), which dates from about 1819 sits on Logan Street, its windows and doors boarded up and the rear wall being held up by a wooden structural support. Hopefully some funds can be located and allocated toward its rehabilitation, as its survival is important to telling the community story.

Monday, December 4, 2017

Recent Acquisitions to My Library

I've been stocking up on some winter reading--as if my "to be read" shelf was not already bulging--but who can resist with such intriguing titles out there.

My interest in hip-hop originated in 1983-84, when it was just finally gaining attention where I lived. I was in 8th grade and became fascinated with break dancing. I watched the movie "Beat Street" over and over on VHS from the local video rental store. Break dancing introduced me to the music that fueled the dancing. It didn't take for me long to get hooked, buying music then like I buy books these days. I've read several so-called histories of hip-hop over the years, but being published by UNC Press adds a even greater sense of credibility to Break Beats in the Bronx: Rediscovering Hip-Hop's Early Years by Joseph C. Ewoodzie, Jr. Here's hoping it give us a whole new way of thinking about hip-hop's early years and its influences.

I've often wondered how difficult it must have been for the enslaved, or even free people of color, to travel in the antebellum United States. Whether free or slave, traveling any distance posed issues that most whites did not have to consider. Well, it looks like I will get my questions answered by reading Colored Travelers: Mobility and the Fight for Citizenship before the Civil War by Elizabeth Stordeur Pryor and published by UNC Press. I'm sure this will be an eye-opening look into a overlooked topic and will certainly be enlightening.

Regional studies on slavery are some of my favorite reading. Slavery differed from area to area due to everything from duration of settlement to crops grown to geography. With the transition from tobacco to a more diversified agriculture, slavery in the Chesapeake and eastern North Carolina changed, too. Money over Mastery, Family over Freedom: Slavery in the Antebellum Upper South by Calvin Schermerhorn examines this transition, its effect on slave families, and in turn, their effect on the American marketplace.

My visit to the Sunflower State in 2010 for a conference, and thus my subsequent museum and historic site visits there only served to fuel my then growing interest in learning more about "Bleeding Kansas." Although this subject has not received a tremendous amount of scholarship in the past decade, Stark Mad Abolitionists: Lawrence, Kansas, and the Battle over Slavery in the Civil War Era, by Robert K. Sutton, and published by Skyhorse, may just reignite an new examination of the importance of this particular place and time.

Slavery's spread to the Old Southwest in the first half of the nineteenth century drastically transformed the United States. Migrating planters and their transported human property, along with the rise in the interstate slave trade, changed the politics, economy, and society of areas like Texas as much as they did the physical landscape. Seeds of Empire: Cotton, Slavery, and the Transformation of the Texas Borderlands, 1800-1850, by Andrew J. Torget (UNC Press), promises to provide readers with a better understanding of how slavery's introduction into Mexican territory helped lead to the Texas Revolution, the Mexican War, and the Civil War.

Now the challenge becomes finding the time to read these great titles. What a wonderful problem to have!

Friday, December 1, 2017

Andrew Johnson Speaks to Black Crowd in Nashville

This news snippet of a speech made on October 24, 1864, by Andrew Johnson was found printed on the third page of the document I shared in yesterday's post. I thought I'd share it, too, as it caught me a little by surprise. Knowing Johnson's seeming about-face when he assumed the presidency after Lincoln's assassination makes these comments intriguing.

Johnson, never a friend of the Southern aristocracy, came from humble beginnings. He ran away as a apprentice tailor in North Carolina as a young man and eventually set up his own shop in Greeneville, Tennessee, where he was self educated with the help of his wife. Johnson became involved in politics, serving in the state legislature, then the US House of Representatives, Governor of Tennessee, and the US Senate. He was the only senator from a seceded state who did not resign his seat. Johnson was appointed Military Governor of Tennessee during the Civil War by Lincoln and then became the Old Abe's vice presidential choice after the election of 1864.

As president Johnson still abhorred those former Confederate aristocrats who sought his pardon, but he also saw that their rights were restored as well as their previously confiscated lands. His promises of protection and equal rights for African Americans, as expressed above, was seemingly forgotten in his attempt to reconcile the sectional divisions the war had finally settled with arms.

Johnson image and text image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)