Tuesday, June 30, 2020

Battle of New Market Heights Memorial & Education Association's Website Now Live

I am so happy to end June 2020 by sharing some great news. The Battle of New Market Heights Memorial and Education Association's (BNMHMEA) website is live! You can now keep up with the organization's efforts to memorialize the soldiers of the United States Colored Troops and educate the pubic about their courageous acts in the September 29, 1864 battle. If you are not aware, 14 African American soldiers and two white officers from the 3rd Division of the XVIII Corps in the Army of the James received the Medal of Honor for their bravery and heroism. People need to know about their inspiring story!

On the website you can read the stories of a number of the men who fought at New Market Heights. Be sure to check back often, as new stories are being added all the time. The website also allows visitors to support BNMHMEA's twin goals of memorialization and education by becoming a member and or giving a kind donation.

BNMHMEA hopes that you become a frequent visitor to the website and its accompanying Facebook page.

"Three Medals of Honor" image courtesy of Don Troiani

Saturday, June 27, 2020

A Soldier's Trials and Tribulations

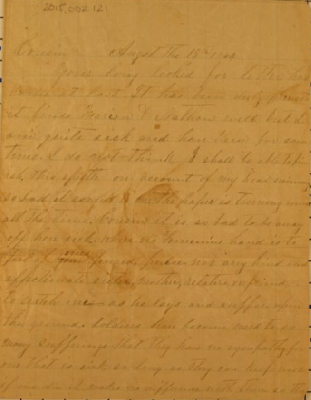

One of the things that often comes out

in Civil War soldier’s letters is the toll that military service took on one’s

body, mind, and spirit. Experiencing hard fighting, eating bad food, enduring

long marches, and living out in all types of weather wreaked havoc on men’s

physical and mental systems.

The Petersburg Campaign’s summer months

of 1864 were particularly trying. After almost a month of constant combat in

May and early June, the fighting transitioned to Petersburg for control of the

area’s roads and railroads. On August 18, 1864, Lt. Joseph G. Younger of

Company F, 53rd Virginia Infantry, sat down to write a letter to a

cousin. This letter is now in the collections of Pamplin Historical Park and

the National Museum of the Civil War Soldier. Younger opened by stating that he

had received his kinsman’s letter that he had “long looked for.”

Fighting in Company F with Younger were

his brothers, Francis Marion and Nathan B. Younger. He informed the recipient that

both of them were fine, but that he himself was not feeling well and had been

sick “for some time.” Younger gives the reader a hint of his symptoms. “I do

not think I shall be able to finish this epistle on account of my head swimming

so bad it seems to me the paper is turning ‘round all the time.” Perhaps

Younger was suffering from a high fever, or consequences of heat exhaustion.

Regardless, he ached for kind medical attention: “Cousin, it is so bad to be

away off here sick, where no feminine hand is to feel of one’s pulse, or any

kind and affectionate sister, mother, relative, or friend to watch one as he

lays and suffers upon the ground.”

Younger had enlisted in July 1861, and

over his three years of service had experienced many hardships and viewed

terrible sights on various battlefields. Soldiers often mentioned the callous

nature that built up over time. Younger mentioned it, too. “Soldiers here

become used to so many sufferings that they have no sympathy for one that is

sick, so long as they can keep well. If one dies it makes no difference with

them . . . . If one gets killed in battle it is the same case,” he wrote.

For a few lines—perhaps forcing his

thoughts in a more pleasant direction—Younger writes about some of the young

ladies back home and their current situations. However, soon he is right back

to his present experience, without even a transition. “There was terrible

shelling at Petersburg this morning before day. I have not heard the cause of

it. We will have hot times here soon I think. A good deal of sickness is

getting among our soldiers.”

With so much hardship to endure it is

easy to see how one might become somewhat disheartened. That sentiment comes

though: “I am in hopes the war will end soon. I have thought it would end this [past]

winter, but I do not know how it will end, nor when. I know this much; it

cannot end too soon for us. I think it has as well end this winter as to go on

next spring, for it will never end by fighting no-how.”

Younger’s last thoughts include a few

lines about facing African American Union soldiers in battle, or the “Yankee

negro,” as he termed them. “I think if they fight negroes against us, we ought

to conscript some of ours to meet them. I reckon our negroes will fight as well

as theirs,” Younger wrote. He concluded the letter much as he started it: “I

must close as I am getting so weak I cannot sit up. Write soon. I remain your

affectionate cousin.”

Younger transferred to an artillery unit

in December 1864 and survived the war. He died in Arkansas in 1916.

Saturday, June 20, 2020

A Confederate Captive at Five Forks

|

| Confederate Soldiers Captured at Five Forks, Virginia, and their Guards |

Moore was an eager and early enlistee. He signed up on May 14, 1861, in Richmond, his home town. Absent sick for a significant amount of his service, Moore returned from the hospital due to a severe case of diarrhea on January 2, 1865.

The 15th Virginia, part of Gen. Montgomery Corse's Brigade in Gen. George E. Pickett's Division, served on the Bermuda Hundred Peninsula during much of the campaign. However, they were transferred to Dinwiddie County in late March 1865 and ordered to hold the important crossroads at Five Forks. On March 31, Pickett's Division battled Union Gen. Philip H. Sheridan's force near Dinwiddie Court House. The Confederates did well, but due to pressure from the V Corps on other Southern forces along White Oak Road, Pickett fell back to Five Forks. Ordered by Lee to hold Five Forks at all hazards, Pickett and other Confederate commanders neglected to maintain proper vigilance. When attacked by Sheridan's cavalry and the V Corps, the Southern resistance proved too meager to make a stand.

Caught up in the turmoil west of the Five Forks intersection was Corse's Brigade, the 15th Virginia, and of course, Pvt. Moore. In his reminiscences, published at the beginning of the 20th century, Moore explained the situation: "We were in a cul de sac produced by the forks of the roads. I continued to fire as before, but after firing about ten or twelve rounds my ramrod got hung in the gun, and I was about to fire ramrod and all into a cavalryman, who was about to shoot me, when someone dismounted him. I got the ramrod down again and resumed my position on the ground."

Moore was about to fire into a group of enemy soldiers when he heard a "click, click" and received an order to surrender. Moore claimed, "I threw up my hands in token surrender, and with many others was ordered to the rear. Nearly half of our division (Pickett's) captured.

As was often the case with battlefield captives, they were marched off the field to a relatively safe location away from the fighting. Moore said that, "I confess when ordered to throw down my rifle and go to the rear I felt very sad, but I also felt a relief that it was over, and that the inevitable had come . . . . As I threw my half emptied cartridge box into a ditch I breathed a prayer of thankfulness to God, Who had spared my life."

During my research I've located numerous accounts from Union soldiers who were robbed of their equipment, food, and money from their Confederate captors. However, Moore claimed that he was "ordered to open our haversacks and surrender their contents." Moore told them that as he was now a prisoner he needed his surplus clothes. They let him keep his underwear but he had to give up half of his tobacco and the little food he had. Moore borrowed a pocket knife from one of the guards and conveniently forgot to return it, "which proved useful in prison."

Moore and the other Confederate prisoners were marched from Five Forks to City Point, the Union supply base and command center located at the confluence of the Appomattox and James Rivers in Prince George County. Moore remembered plodding along the muddy road, not allowed to walk in fields beside the roads. Escorted partly by Union cavalry, he felt an attempt at escape was futile. When he arrived at City Point, Moore was amazed at the Union's stock of wagons, artillery, and reserve troops.

From City Point, the prisoners were put aboard ships for transport to Point Lookout, Maryland's POW camp. Moore and the others were issued hardtack and salt pork rations to eat on the trip. His service records tell us that he took the oath of allegiance on June 15, 1865, and was released.

After the war, Moore married, had a son, and worked in the grocery business in Richmond. He died on May 13, 1913, just about a month shy of his 70th birthday. He now rests in peace in Hollywood Cemetery.

Monday, June 15, 2020

Col. Joseph Kiddoo Reports on Baylor's Farm Fight, June 15, 1864

The United States Colored Troops division of the XVIII Corps, Army of the James, certainly saw their fair share of combat during the Petersburg Campaign. These soldiers are best known for their fighting late in the day on June 15, 1864, taking several battery emplacements on Petersburg's Dimmock Line, and, of course later, at the Battle of New Market Heights on September 29, 1864.

However, often overlooked is their true baptism in combat early on the morning of June 15 at Baylor's Farm during the approach to Petersburg's defensive line.

The USCT division, commanded by Gen. Edward Hinks, consisted of two brigades. Col. Samuel A. Duncan led the brigade composed of the 4th, 5th, 6th, and 22nd United States Colored Infantry regiments. Col. John H. Holman was in charge of the other brigade, which only contained the 1st USCI and 5th Massachusetts Colored Cavalry.

During the night of June 14/15, Duncan's Brigade moved from their encampment at Point of Rocks on the Bermuda Hundred to the south side of the Appomattox River via a pontoon bridge placed at Broadway Landing. At near the same time, Holman's Brigade moved from their City Point camps to junction with Duncan's Brigade in preparation to attack Petersburg. White divisions in the XVIII Corps maneuvered just to the west, near the City Point Railroad line.

Blocking Hink's route to Petersburg along the City Point Road was an earthwork emplacement containing infantry and artillery at Baylor's Farm. The location of this engagement is now near where I-295 and Hwy. 36 intersect in Prince George County, on the southwest side of Hopewell, Virginia.

The following is the portion of Colonel Joseph Kiddoo's (22nd USCI) official report that concerns the action at Baylor Farm:

"On the morning of the 15th I moved with the rest of the brigade from Spring Hill on the City Point road. Approaching the enemy's advanced line of rifle-pits near Baylor's house, I received orders from the colonel commanding the brigade [Duncan] to form line of battle and advance, the Fifth U.S. Colored Troops being at the same time on my right and the Fourth U.S. Colored Troops on my left. I also received orders from the colonel commanding to be ready to charge when ordered. After I had gotten under the fire of the enemy's artillery, concluding that on account of the broken nature of the ground orders could not reach me to charge, or that I could not be found, I took the responsibility and ordered my regiment to charge the line of rifle-pits in my front. The effect with which the enemy's artillery was playing upon my line was the strongest inducement for me to give this order. The charge was gallantly made, and that portion of the rifle-pits in front of my line possessed, together with one 12-pounder howitzer, from the fire of which my men suffered severely while coming through the woods. From thence I marched with the rest of the brigade to the left and toward the main line [Dimmock Line] of the enemy's works."

As Kiddoo's men charged, they yelled "Remember Fort Pillow!" The New York Herald correspondent, Mr. J. A. Brady, shared a report that published on June 20, 1864. It reads:

"With a wild yell, that must have certainly struck terror into the hearts of their foes, the Twenty-second and Fifth United States colored regiments, commanded by Colonels Kidder [sic] and Conner, charged under a hot fire of musketry and artillery over the ditch and parapet, and drove the enemy before them capturing a large brass field piece, and taking entire possession of their works."

Brady continued: "When the negroes found themselves within the works of the enemy no words could paint their delight. Numbers of them kissed the gun they had captured with extravagant satisfaction, and feverish anxiety was manifested to get ahead and charge some more of the rebel works. A number of the colored troops were wounded and a few killed in the first charge. A large crowd congregated, with looks of unutterable admiration, about Sergeant Richardson and Corporal Wobey [sic], of the Twenty-second United States colored regiment, who had carried the colors of their regiment and had been the first men in the works."

However, often overlooked is their true baptism in combat early on the morning of June 15 at Baylor's Farm during the approach to Petersburg's defensive line.

The USCT division, commanded by Gen. Edward Hinks, consisted of two brigades. Col. Samuel A. Duncan led the brigade composed of the 4th, 5th, 6th, and 22nd United States Colored Infantry regiments. Col. John H. Holman was in charge of the other brigade, which only contained the 1st USCI and 5th Massachusetts Colored Cavalry.

During the night of June 14/15, Duncan's Brigade moved from their encampment at Point of Rocks on the Bermuda Hundred to the south side of the Appomattox River via a pontoon bridge placed at Broadway Landing. At near the same time, Holman's Brigade moved from their City Point camps to junction with Duncan's Brigade in preparation to attack Petersburg. White divisions in the XVIII Corps maneuvered just to the west, near the City Point Railroad line.

Blocking Hink's route to Petersburg along the City Point Road was an earthwork emplacement containing infantry and artillery at Baylor's Farm. The location of this engagement is now near where I-295 and Hwy. 36 intersect in Prince George County, on the southwest side of Hopewell, Virginia.

The following is the portion of Colonel Joseph Kiddoo's (22nd USCI) official report that concerns the action at Baylor Farm:

"On the morning of the 15th I moved with the rest of the brigade from Spring Hill on the City Point road. Approaching the enemy's advanced line of rifle-pits near Baylor's house, I received orders from the colonel commanding the brigade [Duncan] to form line of battle and advance, the Fifth U.S. Colored Troops being at the same time on my right and the Fourth U.S. Colored Troops on my left. I also received orders from the colonel commanding to be ready to charge when ordered. After I had gotten under the fire of the enemy's artillery, concluding that on account of the broken nature of the ground orders could not reach me to charge, or that I could not be found, I took the responsibility and ordered my regiment to charge the line of rifle-pits in my front. The effect with which the enemy's artillery was playing upon my line was the strongest inducement for me to give this order. The charge was gallantly made, and that portion of the rifle-pits in front of my line possessed, together with one 12-pounder howitzer, from the fire of which my men suffered severely while coming through the woods. From thence I marched with the rest of the brigade to the left and toward the main line [Dimmock Line] of the enemy's works."

As Kiddoo's men charged, they yelled "Remember Fort Pillow!" The New York Herald correspondent, Mr. J. A. Brady, shared a report that published on June 20, 1864. It reads:

"With a wild yell, that must have certainly struck terror into the hearts of their foes, the Twenty-second and Fifth United States colored regiments, commanded by Colonels Kidder [sic] and Conner, charged under a hot fire of musketry and artillery over the ditch and parapet, and drove the enemy before them capturing a large brass field piece, and taking entire possession of their works."

Brady continued: "When the negroes found themselves within the works of the enemy no words could paint their delight. Numbers of them kissed the gun they had captured with extravagant satisfaction, and feverish anxiety was manifested to get ahead and charge some more of the rebel works. A number of the colored troops were wounded and a few killed in the first charge. A large crowd congregated, with looks of unutterable admiration, about Sergeant Richardson and Corporal Wobey [sic], of the Twenty-second United States colored regiment, who had carried the colors of their regiment and had been the first men in the works."

The 22nd USCI went on to have tremendous success later that day at Petersburg capturing a portion of the Dimmock Line. However, it is important to remember their marked success earlier in the day, too.

Sunday, June 14, 2020

Flag Day Remembers: Sgt. William H. Carney

Sgt. William H. Carney, Company C, 54th Massachusetts Infantry

Medal of Honor Recipient, May 9, 1900, "for most distinguished gallantry in action . . . ."

"Severely wounded in left hip at assault at Fort Wagner, South Carolina, July 18, 1863."

Born: February 29, 1840 in Norfolk, Virginia

Died: December 9, 1909 in Boston, Massachusetts

"Boys the old flag never touched the ground."

Saturday, June 13, 2020

Corps Badges - Ready Recognition

When the American Civil War began there

was no formal method for a United States Army military organization to

distinguish itself from another. Tradition attributes the conceptual idea of a

corps badge to Maj. Gen. Philip Kearny from the Army of the Potomac. Kearny, a

veteran of the Mexican-American War who had lost an arm in that conflict,

supposedly became frustrated when on a retreat he could not tell his division’s

soldiers from others. Apparently soon thereafter, men started wearing a red

piece of cloth cut into the shape of a “lozenge” or diamond. Kearny received a

mortal wound at the Battle of Chantilly (also known as Ox Hill) on September 1,

1862, but the idea of an army-wide system of corps badges was born.

During the spring of 1863, the Army of

the Potomac, now under the command of Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, instituted a

formal system of identifying the army’s various corps. Apparently, Hooker’s

Chief of Staff, Gen. Daniel Butterfield worked out the basics of the badge

system for the army. Each corps of the Army of the Potomac was designated with

a shape or symbol. For example, the I Corps was a sphere or circle, the II Corp

was a trefoil (clover), the III Corps inherited the lozenge, and the V Corps a

Maltese Cross, etc. In addition, a color denoted each division of each corps.

The first division was red, the second division was white, and the third

division was blue. Therefore, for instance, one could recognize the second

division of the I Corps by its white sphere, and so on.

The corps badges were often no more than

shaped swatches of colored cloth that soldiers often sewed onto their hat or

cap. However some soldiers also sewed corps badges to their uniform jackets,

and some decorated their canteen covers or knapsacks with painted corps symbols.

Soon, other Union field armies adopted

the corps badge system, although they sometimes incorporated different colors

than the Army of the Potomac’s red, white, and blue scheme.

Among the collections at Pamplin Historical

Park and the National Museum of the Civil War Soldier there are a number of

corps badge examples. One, shown here, is from the Army of James’ X Corps.

Constructed of brass, it contains a blue center, indicating that its wearer was

from that corps’ third division. The Third Division of the X Corps was composed

primarily of men serving in various regiments of United States Colored

Infantry.

Thursday, June 11, 2020

Dog Jack

Civil War soldiers often sought ways to

bring pieces of home to war with them as reminders of more pleasant times and to

gain a sense of normalcy. They did so sometimes by adopting a pet mascot.

Common animals like dogs and cats became the boon companions of hundreds of men

in companies and regiments, both Union and Confederate. Some fighting units

preferred more novel mascots. A Mississippi regiment kept a camel named “Old Douglas.”

“Old Abe” was the eagle mascot of the 8th Wisconsin Infantry. Some

men caught and tamed raccoons or other wildlife for their mascots. However,

dogs seemed to be preferred and were the most common Civil War mascots.

Several dogs, like Sallie of the 11th

Pennsylvania, and Jack of the 102nd Pennsylvania Infantry became

famous in the Union’s Army of the Potomac. Sallie, sadly killed in the Battle

of Hatcher’s Run during the Petersburg Campaign was so prized the 11th

Pennsylvania immortalized her on their monument on the Gettysburg battlefield.

Jack’s image appeared in different photographs during the war, one of these

images, a carte de visite, is in the collections at Pamplin Historical Park and

the National Museum of the Civil War Soldier.

Jack’s career as a mascot began even

before the conflict. He appeared one day at the Niagara Volunteer Firehouse in

Pittsburg, Pennsylvania and was quickly adopted by the firemen. When many of

the men went off to fight in the Civil War they took Jack, too, as a good luck

charm.

The 102nd Pennsylvania served

in the Army of the Potomac’s IV Corps early in the war. They saw action during

the Peninsula Campaign, the Seven Days’ Battles—where Jack received a wound at

Malvern Hill, and the Antietam Campaign. It was reported that Jack was very

intelligent and even understood bugle calls. In the fall of 1862, the 102nd

transferred to the VI Corps and experienced fighting around Fredericksburg. In

combat at Salem Church, just outside of Fredericksburg, Jack became a prisoner

of war. Apparently, about six months later, he returned to the 102nd,

formally exchanged in a prisoner swap.

The 102nd Pennsylvania fought

through the severe Overland Campaign in the spring of 1864 and in the

Petersburg Campaign. It was during the VI Corps’ detached service from the Army

of the Potomac, helping protect Washington D.C. in the fall, summer, and winter

of 1864 that Jack went missing at Frederick, Maryland. Some of the regiment’s

soldiers believed he was taken for his expensive silver collar. Jack was never

heard from again. The 102nd mustered out of Union service in June of

1865 but remembered Jack by having his portrait made from one of his famous

photographs. Such were the strong bonds between some soldiers and their

mascots.

Wednesday, June 10, 2020

Dying Far From Home - Pvt. Richard Armstrong, Co. A., 38th USCI

It has been some time since I last shared a "Dying Far From Home" post. Way too long, actually. In all of my previous posts I've included a headstone photograph of the soldier profiled. However, I am unable to do that for this particular story. It will become apparent why that is as you read. But, first, a related aside.

I opened 2020 here on Random Thoughts on History by sharing news concerning the formation of the Battle of New Market Heights Memorial and Education Association (BNMHMEA). We had our first board meeting in late February. The next board meeting will be on June 20. Things continue to progress nicely. Hopefully it won't be too much longer until I can share a link to the organization's website. I've had a "sneak peak" look at it, and I am very pleased with its look and the educational information it offers readers. One section of the website is titled "Soldier's Stories." Its purpose is probably obvious--to tell the life stories of the African American enlisted men and non-commissioned officers, and white commissioned officers, who fought in the United States Colored Troops (USCT) regiments at New Market Heights. It includes those who are famous, like some of the 14 black Medal of Honor recipients, but it also covers some men that few people have heard of. The following story is one of those little known soldiers. They deserve to be remembered, too.

The USCT regiments who participated in the primary assaults at New Market Heights were the 4th, 5th, 6th, 36th, and 38th USCI. The 1st, 22nd, and 37th USCI, and 2nd US Colored Cavalry also supported the attack. Browsing through the service records of these regiments one comes across soldier after soldier who gave up his life or health by making that historic charge.

Private Richard Armstrong of the 38th USCI is one such soldier. Armstrong's service records give us precious little information about his pre-war life. He was likely enslaved before the war. We do know that Armstrong was born in Norfolk County, Virginia, and later lived in Princes Anne County. His occupation is noted as "farmer," and the army described him as five feet, six inches tall, with a "dark" complexion. Pvt. Armstrong's age at his enlistment is given as 17. Other records later in 1864 indicate he was 19.

Richard Armstrong's Civil War experience apparently began with his enlistment on January 11, 1864, in Norfolk. He formally mustered into Company A, 38th USCI on January 23. He signed up for three years, but would ultimately serve less than a year. Armstrong's records show he was always present for duty until his September/October 1864 card. That one shows him as absent by reason of "wounded in action Sept. 29/'64. Sent to Hospital."

Of course, September 29, 1864, marks the Battle of New Market Heights. Other information in Armstrong's service records tell of the wounds he received on the battlefield. A hospital card from Summit House General Hospital in Philadelphia shows that Armstrong received wounds to his right hand and right thigh. The wound to his right thigh is described as a "compound fracture of femur," caused by a minie ball.

It appears that after being wounded at New Market Heights, Armstrong initially received treatment at the vast hospital complex at City Point, Virginia. Perhaps due to the seriousness of the wound to his thigh, Armstrong transferred to Summit House hospital in Philadelphia. His hospital records do not indicate whether he endured an amputation, which was a common treatment for similar wounds that broke bones in the extremities. A hospital "Treatment" card only states that Armstrong received: "Cold water dressing and stimulants internally."

Despite whatever treatments Armstrong did receive, they ultimately proved ineffective, as he died on October 31, 1864; just over a month after his wounding.

Pvt. Armstrong was buried the day after his death in Philadelphia's Lebanon Cemetery, a predominately African American burial ground. Notable black individuals such as Octavius V. Catto and Absolom Jones were also buried in Lebanon Cemetery. Apparently, Lebanon was condemned in 1899 and the burials were reinterred in Eden Cemetery in Collingdale, Pennsylvania. Armstrong apparently now rests in Eden among famous African Americans including Underground Railroad operative William Still and opera star Marian Anderson. If anyone happens to be in the area and is able to locate and photograph Armstrong's grave (if it is marked), I would be happy if they would share a copy with me.

Young Pvt. Armstrong performed his enlistment commitment faithfully. He ended up giving his life serving a country that did not yet recognize him or people of his race as citizens. It was with the hope of citizenship, and being treated as an equal, that many black men risked their lives fighting in USCT regiments. Is a purer sacrifice possible for a soldier?

Sunday, June 7, 2020

Recent Acquisitions to My Library

I posted a few weeks back about the 2020 Pulitzer Prize winning history book citing a post I made here on "Random Thoughts on History." In that post I mentioned that I had been monitoring the price of Sweet Taste of Liberty: A True Story of Slavery and Restitution in America by W. Caleb McDaniel. After receiving the Pulitzer Prize its price went up considerably, but then dropped again and I snatched up a used copy in great condition. I am really looking forward to delving into this Kentucky story about an early case of justice to right a grave injustice.

As I've been posting and mentioning for some time that I am constantly on the search for prisoner of war accounts from the Petersburg Campaign for a study that I am currently working on. Well, I happened to stumble upon As if it were Glory: Robert Beecham's Civil War from the Iron Brigade to the Black Regiments, edited by Michael E. Stevens a few weeks back and found an inexpensive soft cover copy. Beecham's story, although a memoir written in 1902, tells of his long service as a soldier, first in the 2nd Wisconsin Infantry and then as an officer in the 23rd USCI. During the Battle of the Crater, Beecham was captured and held in South Carolina. Although I have already noted several cases of Crater captures, I look forward to finding out more about Beecham's personal experience.

Keep reading!

Sunday, May 31, 2020

4th Offensive Union Prisoners as Reported in the Richmond Daily Dispatch

Each of Gen. Ulysses S. Grant's offensives to take Petersburg resulted in not only killed and wounded soldiers, they also produced thousands of prisoners. The high price for the territory gained with each move forward were casualties of all kinds. I am continuing to find prisoner reports in Richmond newspapers for most every offensive. The above short story, relaying information on the Battle of Globe Tavern, aka Weldon Railroad, and Second Deep Bottom, ran in the Tuesday, August 23, 1864, edition of the Richmond Daily Dispatch.

1,474 prisoners at Globe Tavern, and 30-some from Deep Bottom, goes to show the large numbers being captured, often when Confederates counterattacked the initial offensive. What I want to get a better idea about is if these prisoners are largely finding themselves in helpless circumstances (i.e flanked or surrounded) where they truly have no other real choice other than to surrender, or are there instances where the will to fight is lacking, whether as a way to preserve their lives or from physical exhaustion? And, do the reasons for so many prisoners being captured change over the span of the Petersburg Campaign?

The Daily Dispatch ran another notice (above) on Monday, August 29, 1864. It mentions that since "Friday night last," which would be since August 26, 2,100 Union prisoners arrived at Libby prison in Richmond. The vast majority of these men were "captured in the neighborhood of Petersburg," likely at the Battle of Reams Station (Aug. 25), south of where the fighting occurred a few days earlier at Globe Tavern and where the II Corps suffered a significant defeat. The notice also mentions that an additional 300 were captured at Lynchburg.

The search continues.

Friday, May 29, 2020

Lt. William H. Appleton, 4th USCI, Medal of Honor Recipient

The 14 African American soldiers who earned the Medal of Honor for their heroic acts at the Battle of New Market Heights set a high standard for courage under fire. William H. Barnes, Powhatan Beaty, James H. Bronson, Christian A. Fleetwood, James Gardiner, James H. Harris, Thomas R. Hawkins, Alfred B. Hilton, Milton M. Holland, Miles James, Alexander Kelly, Robert A. Pinn, Edward Ratcliff, and Charles Veal, are all listed when internet search requests reveal information on New Market Heights medal recipients.

However, less well known, and often not named among the New Market Heights recipients are two white officers whose Medals of Honor also came through brave acts on September 29, 1864. Of the two, Lt. Nathan Edgerton, 6th USCI, has probably received more notice by being included in Civil War artist Don Troiani's amazing painting, "Three Medals of Honor." Edgerton is portrayed in the image protecting the national and regimental colors, along with fellow medal recipients, Thomas R. Hawkins and Alexander Kelly. The Medal of Honor recipient from New Market Heights that is most forgotten is Lt. (later Captain) William H. Appleton of the 4th USCI.

William Appleton was born in Chichester, Merrimack County, New Hampshire on March 24, 1843. Appleton appears in the 1860 census in his wheelwright father Samuel's household. At age 19, in May 1861, Appleton enlisted in Company I, 2nd New Hampshire Infantry. They fought at First Manassas, the Peninsula Campaign, 2nd Manassas, Fredericksburg, and Gettysburg before Appleton joined as Company H's 2nd lieutenant in the 4th United States Colored Infantry when he officially joined the new unit in August 1863.

Appleton's service records indicate he was a faithful soldier, as he always shows as present for duty. He must have performed quite well during the 4th USCI's participation in the initial attacks on Petersburg's defenses, as his Medal of Honor citation includes the following: "The first man of the Eighteenth Corps to enter the enemy's works at Petersburg, Va. 15 June 1864." That heroic action must have also helped him earn his promotion to first lieutenant, which he received the following month.

Although the 4th USCI led the charge at New Market, during the fight, Appleton somehow came through it unscathed. Several of the 4th's other white officers were not as fortunate. Capt. Samuel W. Vannings of Company E was killed in action. Five other line officers were wounded: Capt. Wareham Hill, Lt. J. Murray Hoag, Lt. Thomas N. Price, Lt. Daniel W. Spicer, and Lt. W. Watson Gillingham. Appleton's Medal of Honor citation also states, "Valiant service in a desperate assault at New Market Heights., Va., inspiring the Union troops by his example of steady courage."

Appleton's courage netted him not only the Medal of Honor; he also earned promotion to captain in Company E to fill the vacancy of the deceased Samuel Vannings. The 4th USCI transferred to North Carolina and participated in the fighting to capture Fort Fisher in January 1865, the capitulation of Wilmington, and the occupation of Goldsboro and Raleigh. They remained in North Carolina, being among the USCT units that did not have to go to do duty on the Texas-Mexico border. Appleton and the 4th USCI mustered out of service in May 1866.

William Appleton's post-war life is unfortunately not easy to track. He received his Medal of Honor in 1891 and died at 69 years old in 1912. He was buried in his native Merrimack County, New Hampshire in Evergreen Cemetery. May he not be forgotten for his heroic part in preserving the Union, ending slavery, and his service in the United States Colored Troops.

Sunday, May 24, 2020

"God Bless the Old Sixth Corps"

The VI Corps was among the most accomplished in the Army of the Potomac. Through several different leaders, the VI Corps time and again carried out its orders and did so well. Their battle record was enviable for any similar sized unit in the American Civil War. Fighting under the "Greek Cross" corps badge they developed a fine reputation.

I get to talk about the VI Corps at work often. They were, after all, the stars of the April 2, 1865, breakthrough at Petersburg, which is preserved today by Pamplin Historical Park. I've made it point to try to learn what I can about their service during the Civil War, particularly in 1864-65.

This past week, while reading about the VI Corps' role in the Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1864, when they were detached from the Army of the Potomac to serve the the Army of the Shenandoah, and led by Philip H. Sheridan, I came across a reference to a song titled "God Bless the Old Sixth Corps."

Written in 1865 by Thomas P. Ryder (1836-1887), and as one might imagine, the song gives the VI Corps a heap of well-deserved praise.

God Bless the Old Sixth Corps

God Bless our noble army!

The hearts are strong and brave,

That have willingly come our standard

From treason's grasp to save,

But from the Western Prairie

To Atlantic's rocky shore,

The truest, noblest hearts of all

Are in the Old Sixth Corps.

Chorus-

Then, ere we part tonight, boys,

We'll sing one song the more.

With chorus swelling loud and clear

God bless the Old Sixth Corps!

In the thickest of the battle,

Where cannon's fiery breath

Smites many a strong heart pressing,

On to victory or death.

The foremost in the conflict,

The last to say, "'tis o're",

Who know now what it is to yield

You'll find the "Old Sixth Corps."

Chorus-

There's many a brave many lying,

Where he nobly fought and fell,

There's many a mother sighing,

For the sons she loved so well.

And the Southern winds are breathing

A requiem where they lie,

O' the gallant followers of the cross

Are not afraid to die!

Chorus-

Our truest, bravest heart is gone,

And we remember well

The bitter anguish of that day

When noble Sedgwick fell.

But there is another left,

To lead us in the fight,

And with a hearty three times three

We'll cheer our gallant Wright!

Chorus-

Then on! Onward we will press,

Till treason's voice we still,

And proudly waves the "Stripes and Stars",

On ev'ry Southern hill.

We'll struggle till our flag is safe,

And honored as before,

And men in future times will say,

God bless the Old Sixth Corps.

Chorus-

Monday, May 18, 2020

Henry McNeal Turner Comments on USCTs Executing Confederate Prisoners

In conducting my research on prisoners of war captured during the Petersburg Campaign, I've come across instances where soldiers captured on the battlefield were killed by their captors. The most famous example of this type of atrocity comes from the Battle of the Crater (July 30, 1864), where Gen. William Mahone's division counterattacked and in the process executed black soldiers of the IX Corps' 4th Division. Many of the United States Colored Infantry soldiers went into that engagement yelling, "Remember Fort Pillow" for motivation. Of course, Fort Pillow refers to the fight on April 12, 1864, where Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest's Confederate cavalry demanded surrender of that Tennessee military installation along the Mississippi River. When the Union interracial garrison force refused the Confederate demand, the Southerners overran the defenses and killed scores of the black soldiers who attempted to capitulate. There are also references to African American soldiers being killed after surrendering during the early actions of the Battle of New Market Heights and also later that day at Fort Gilmer.

While reading Will Greene's Campaign of Giants there was mention that black soldiers killed some Confederate soldiers in retaliation for Fort Pillow. During the June 15, 1864, assaults on Petersburg's Dimmock Line of defenses, USCTs in Gen. Edward Hincks's division of the XVIII Corps successfully breached the earthworks, capturing some of the defenders, a few of whom were apparently dispatched.

Henry McNeal Turner, chaplain for the 1st United States Colored Infantry, seems to corroborate this information in his June 30 report to the Christian Recorder newspaper. In this letter Turner gives some details about the fights at both Baylor's Farm and along the Dimmock Line. Turner also tells about the motivation of Fort Pillow, and black soldiers killing Confederate prisoners; albeit doing so in careful phrasing. Turner wrote:

"The rebel balls would tear up the ground at times and create such a heavy dust in front of our charging army that they could scarcely see the forts for which they were making. But onward they went, through dust and every impediment, while they and the rebels were both crying out -- 'Fort Pillow.' This seems to be the battle-cry on both sides. But onward they went, waxing stronger and mightier ever time Fort Pillow was mentioned. Soon they boys were at the base of the Fort, climbing over abatis, and jumping the deep ditches, ravines, &c. The last load fired by the rebel battery was a cartridge of powder, not having time to put the ball in, which flashed and did no injury.

The next place we saw the rebels was going out the rear of the forts with their coattails sticking straight out behind. Some few held up their hands and pleaded for mercy, but our boys thought that over Jordan would be the best place for them, and sent them there, with few exceptions."

So, what does Turner mean by "over Jordan would be the best place for them?" Going over the Jordan River to the "Promised Land" is a metaphor for going on to the afterlife, and would have well been understood by mid-19th century Americans.

At this, Turner's first mention of dispatching Confederate prisoners, he writes with a somewhat cavalier attitude. However, toward the end of the correspondence he offers some deeper thoughts on killing prisoners. He wrote:

"There is one thing, though, which is highly endorsed by an immense number of both white and colored people, which I am sternly opposed to, and that is the killing of all the rebel prisoners taken by our soldiers. True, the rebels have set the example, particularly in killing the colored soldiers; but it is a cruel one, and two cruel acts never make one humane act. Such a course of warfare is an outrage upon civilization and nominal Christianity. And inasmuch as it was presumed that we would carry out a brutal warfare, let us disappoint our malicious anticipators by showing the world that the higher sentiments not only prevail, but actually predominate."

Turner's last thoughts on battlefield atrocities stands in stark contrast to that offered by some of the Richmond newspapers, who called for continued acts by Confederate soldiers.

Friday, May 15, 2020

Recent Acquisitions to My Library

For the past ten years or so a handful of environmental Civil War studies have appeared in print. Books like Nature's Civil War by Katherine Shively Meier, Ruin Nation by Megan Kate Nelson, and War Upon the Land by Lisa M. Brady, among a few others, have helped shed light on how armies and the environment influenced one another. Adding to this growing body of literature is An Environmental History of the Civil War, coauthored by Appalachian State University professors Judkin Browning and Timothy Silver. I've seen and heard a couple of online interesting interviews with the authors about the book's topical areas and how they shared research and writing responsibilities. As I am a proud Appalachian State alum, I look forward to diving into it.

Since the late 1990s, I've been collecting hardback editions of UNC Press' Military Campaigns of the Civil War series. Noted historian Gary Gallagher edited all of the books in the series until the last couple of books, which were Cold Harbor to the Crater, co-edited with Caroline Janney, and Petersburg to Appomattox, solo edited by Caroline Janney, who followed Gallagher as the John L. Nau Professor of Civil War history at the University of Virginia. The only edition that I was lacking was The Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1864. Well, I found a decent price on a used copy and I now have the complete set. I've heard rumors that additional editions covering eastern theater campaigns not previously examined, such as First and Second Manassas, may be published in the near future. Let's hope so!

One of the 13 "soldier comrades" at Pamplin Historical Park and National Museum of the Civil War Soldier's permanent exhibit ,"Duty Called Me Here," is 28th Massachusetts Infantry soldier Peter Welsh. Some of this Irish Brigade fighting man's letters are used to help tell his experience within the exhibit. However, I'm looking forward to reading his full extant body of letters which are collected in Irish Green & Union Blue: The Civil War Letters of Peter Welsh, edited by Lawrence Frederick Kohl and Margaret Cosse Richard. There is nothing quite like reading the words right from the soldiers' pens.

Happy reading!

Thursday, May 14, 2020

Random Thoughts on History Cited in 2020 Pulitzer Prize Winner for History

A few months back, I decided to Google "Tim Talbott and "Random Thoughts on History" just to see what turned up. Among the first hits was a link to the recently published Sweet Taste of Liberty: A True Story of Slavery and Restitution in America by W. Caleb McDaniel. By coincidence, several months earlier, I had read an article in Smithsonian magazine on the book's topic, also penned by the author.

Being that it was a Kentucky-based story, involving slavery and law, and involving a historical personality (Zeb Ward) with whom I'd researched when I lived in the Bluegrass State, I was certainly interested in obtaining the book and immediately placed it on my book "wish list."

In Sweet Taste of Liberty, McDaniel cited my article from "Random Thoughts on History" about some African American men previously owned by Zeb Ward and who enlisted in United States Colored Troops regiments during the Civil War. It is an honor for a fellow historian to use some of my research, but it is especially so when that historian's study results in such a prestigious award as the Pulitzer Prize.

Hoping to get a copy of Sweet Taste of Liberty for a reasonable price, I have checked my wish list often to monitor the used price rate. I probably should have grabbed a copy at the $15.00 it was once going for, because now that it has earned the Pulitzer it is priced over $40.00. Proof positive of the effects book awards can have.

Monday, May 11, 2020

Henry McNeal Turner Comments on White Soldiers' Attitudes toward Black Soldiers after seeing them in Combat

In my last post I shared some comments by 1st United States Colored Infantry chaplain, Henry McNeal Turner, on how Union soldiers in Washington D.C. treated black people. He observed a marked difference in the attitudes of early enlistees (1861) verses later (1862) ones. I shared my personal take on this as probably partly from a backlash response in the government's changed war aims after the release of the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. I concluded that post wondering if Turner ever observed a positive change in white Union soldiers' attitude toward black soldiers after finally having the chance to see the African American soldiers in combat.

Well, I just finished up Freedom's Witness: The Civil War Correspondence of Henry McNeal Turner and I found my answer. In his June 30 report to the Christian Recorder Turner concluded this column by stating:

"Before closing I would say that the brilliant achievements of our boys in front of Petersburg was more than timed, and did more to conquer the prejudice of the Army of the Potomac than a thousand newspaper puffs. Providentially, the most of that immense army had to pass right by the forts taken by the colored soldiers. Every soldier with whom I came in contact had but little to say except to pay the most flattering compliments to the brave colored men of our division. After that the white and colored soldiers talked, laughed, and ate together with a friendly regard, not surpassing by any previous occasion. Let the forts of Petersburg hereafter add new stars to the glorious constellation, which are glittering with untarnished brilliancy above the horizon. Let them stand a monument to his bravery, heroism, and daring."

In the next post I will share some of Turner's comments on black soldiers' treatment of Confederate prisoners during the June 15 attacks at Petersburg.

Sunday, May 10, 2020

Henry McNeal Turner Comments on Changes in Union Soldiers' Attitudes toward African Americans

I am currently reading Freedom's Witness: The Civil War Correspondence of Henry McNeal Turner, edited by Jean Lee Cole. Turner is not that well known to students of the conflict today, but he was quite a powerful presence in the African American community in Washington D.C. during the Civil War era.

Born free in 1834 in South Carolina, Turner eventually became a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church by age 19. In the late 1850s, Turner and his wife moved to Baltimore to gain further education in the ministry. Moving on to Washington D.C. to lead a church just before the Civil War, Turner also provided insight into happenings in the capital city as the nation divided. Writing for the Christian Recorder, the newspaper for the AME church, Turner provides historians with an important African American voice we do not often hear.

After Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862, it produced a degree of immediate backlash. Many Union soldiers, particularly those from the border states, and southern parts of free states, commented on their motivations being to maintain the Union and not to fight to free the enslaved. A number of border state officers resigned their positions over the issue. However, we rarely hear how the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation affected the black community in some of these areas.

Although Turner credits the observable change in Union soldiers' attitude toward people of color being with early enlistees versus those called later, writing and commenting on this on September 27, I think that the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation's release contributed the lion's share of the attitude change.

"And strange to say too; but there is the greatest difference in the world between the last soldiers called for by the President and the first. The first or former soldiers who came to the defence of their country, seemed to have had nothing at heart by their great and glorious mission, and every other consideration appeared to be a matter of contempt, or regarded as undeserving attention; they passed to and fro among the people and treated everyone respectfully; such were the manners and becoming courtesy of every northern soldier that the colored people delighted to render every assistance in their power; they would take them to their houses and give them the best to eat the market could afford, and divide the last penny they had to make them comfortable, and it was almost unnatural to hear a harsh word spoken by any of them to a colored person. But these last recruits which are coming into the field, are all the time cursing and abusing the infernal negro, as some say, nigger. In many instances you may see a regiment of soldiers passing along the street, and knowing them to be fresh troops, you may (as it is natural) stop to take a look at them, and instead of them thinking about the orders of their commanders, or Jeff. Davis and his army, with whom they must soon contend, they are gazing about to see if they can find a nigger to spit their venom at. And I believe it is to kill off just such rebels as these that this war is being waged for, one in rebellion to their country [Confederate], and the other in rebellion to humanity [Union], for that man who refuses to respect an individual because his skin is black, when God himself made him black, is as big a rebel as ever the devil or any of his subalterns were . . . ."

Tuner, an early proponent for black Union soldiers, went on to recruit for the United States Colored Troops and served as chaplain for the 1st United States Colored Infantry.

I am interested to see later on if Turner observes and comments about a change in the other direction after white Union soldiers see black men in combat.

Wednesday, May 6, 2020

Just Finished Reading - Men is Cheap

“Free Soil, Free Labor, and Fremont” was

an early rally cry for the emergent Republican Party in the mid-1850s. To many

of its Northern proponents, the idea of free labor provided not only a better

economic model, but also staked claim to a moral high ground over the labor

system practiced in the 15 slave states. As most Northerners perceived it, allowing

laborers the ability to choose their profession and their employer, and to earn

their living by the sweat of their brow or by their ingenuity and intellect

without competition from slave labor was clearly superior. Northerners also

felt that slave labor hindered innovation and discouraged industrial trades.

However, as Brian P. Luskey informs us in Men

is Cheap: Exposing the Frauds of Free Labor in Civil War America, the free

labor system was not without its fair share of flaws, too.

Organized into six chapters, Men is Cheap also includes a helpful contextual

introduction and fitting conclusion. In this study we see that the Civil War

provided a good testing ground for the free labor system. As the war progressed

political decisions and military actions produced events that offered certain individuals

and organizations, who were perhaps more interested in personal gain than

national advancement, numerous opportunities to cash in. Corruption involving

Union war material manufacturing contracts have long been part of Civil War

scholarship, but until recently, labor fraud in relation to the Union cause has

largely remained out of the spotlight.

Focusing heavily on what were then called

“intelligence offices,” which operated somewhat like a shadier version of today’s

employment agencies, Luskey exposes a clear contradiction between the ideals of

free labor, and how under the pressures of wartime necessity it sometimes

became manipulated into the corrupt exploitation of vulnerable and marginalized

populations who had few options. While viewed by many Northerners at the time as

less than model citizens, intelligence office brokers also ironically filled

the manpower needs (on the battlefront as well as on the home front) that ultimately

helped facilitate Union victory. They provide quite the intriguing paradox.

Not surprisingly intelligence office

brokers seemed to target those most vulnerable. They sought out the unemployed and

immigrants in the North to fill substitute roles for soldiers who could afford

to buy their way out of service. These middlemen also located recently freed African

American men (once they were finally allowed to officially enlist) to fill the

state quotas required by the federal government. Agents combed the refugee

camps to find freedwomen and children, as well as white Unionist refugees, to

work in Northern homes and on Northern farms at low wages. Even the Confederate

soldier was not out of bounds to these brokers. Confederate prisoners and deserters

who pledged the oath of allegiance to the United States could obtain employment

with the federal government through intelligence office agents. For a price,

agents moved workers to where the work was needed, often, of course, with

little regard for the working conditions or ultimate fate of the worker. In

doing so, these middlemen commodified the worker, not so differently than how the

slave trader had the enslaved.

Men

is Cheap did not provide much

discussion about reform efforts, nor the use of fraudulent free labor as a

political tool. Perhaps there were few attempts at reform due to the constant

focus on prosecuting the war, but I would be surprised, if at minimum, the

Democratic Party or “Copperhead” factions did not at least mention instances of

this abuse if effort to gain political ground.

Regardless, Men is Cheap makes a significant contribution to the body of Civil

War scholarship, particularly that relating to the growing genre of labor

history. How the United States came to regard labor developed in part from the

Civil War years, and its relevance is still clearly present in today’s society.

Thursday, April 30, 2020

Recent Acquisitions to My Library

With the uncertainty that comes with our nation's present situation, I've been trying to limit my purchases to the necessities. However, I've come across a few intriguing titles at good prices, so I decided to also try to do my little part to help buoy the consumer confidence figures.

I'm a big fan of social history studies. Over the past 40 years or so historians have tackled a diversity of topics; everything from sensory history to how clocks and time keeping have changed how people of the past lived. With American Lucifers: The Dark History of Artificial Light, 1750-1865, author Jeremy Zallen looks into a subject we all too often take for granted in the 21st century . . . until we lose power. It looks to be an enlightening read! Pun intended.

I first became acquainted with Sam Wineburg's writing while working with history educators in Kentucky. His books like Reading Like a Historian, and Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts, along with his work with the Stanford History Education Group were effective in getting teachers to think about how to make their instruction more effective. His latest book, Why Learn History (When it's Already on Your Phone) shows that historical thinking skills are still important despite having information available virtually at the swipe of a screen. Historical thinking goes far beyond just reciting facts. It is about weighing evidence and judging the soundness of arguments, among other things. I can't think of much anything more needed in our society right now.

I think I've mentioned several times before that I'm not a big reader of historical fiction, but every now and then it's nice to take a break from the historical arguments and theoretical approaches of academic books and just dive into a good story. I became aware of Two Brothers: One North, One South by David H. Jones about 12 years ago when it first came out. Based partly on events that occurred during the April 2, 1865 Petersburg Breakthrough, and involving a Maryland family's brother versus brother situation, it has the potential to be quite an interesting tale. We shall see.

Happy reading! Stay well!

Sunday, April 26, 2020

Two Soldiers from North Carolina - One Union, One Confederate

I find it interesting to think about what makes people who come from the same geographical area experience such different paths in life. While theoretically "all men are created equal," in practice that has never been quite so. Differences in socioeconomic status, education, family connections and opportunities all often help determine what choices we make and what we ultimately end up doing. Those differences were enhanced with people of the past, especially those of the Civil War-era, where our democratic form of government did not recognize some people as formal citizens.

Recently in my reading, I came across mention of William Davis, who served in the 36th United States Colored Infantry (USCI). Originally known as the 2nd North Carolina Colored Infantry, the men from the 36th USCI came largely from northeastern North Carolina and southeastern Virginia. When those areas were occupied by Union forces early in the Civil War, enslaved families made their way to Union lines seeking freedom and opportunity. When African Americans were finally allowed to enlist in the U.S. army, many of the refugee men signed up. William Davis enlisted in Company E on August 15, 1863, in Norfolk, Virginia. His service records state that he was 26 or 27 years old and born in Halifax County, North Carolina. Enlisting officers wrote his occupation as "farmer," but in fact, before joining the U.S. army, Davis was enslaved.

William Davis must have shown leadership ability very early on during his military service, as he was made sergeant only three days after enlisting. In early 1864, he received promotion to 1st sergeant. Davis's leadership was tested at the Battle of New Market Heights on September 29, 1864. While many of the white officers in that fight went down with wounds, non-commissioned officers like Davis stepped in and carried the enemy's works. Davis remained with the 36th USCI through their post war experience on the Texas-Mexico border, and finally mustered out with the expiration of his enlistment on August 15, 1866.

The 1870 census shows Davis back in North Carolina. At that time he lived in New Bern with his wife Sarah, who he apparently married while enslaved. Henry Davis (15) and Lovenia Davis (19) are also in his household and may or may not have been William's children. At that time Davis's job was "farmer." It seems Davis moved back to his native Halifax County by 1880, as he is there in that census although with a different wife (Violet), and three young children. I was not able to definitively find other records for Davis or determine his death date.

Another man from Halifax County, and one who I located during my research on Petersburg Campaign prisoners, was Octavius Augustus Wiggins. Born just a few years later than William Davis, Wiggins experienced a much different life that of Davis. Wiggins's race, social status, family, and education helped determine such.

Wiggins appears as 6 years old in the 1850 census. His father, 52 year old Mason, a "farmer," is shown owning $4000.00 in Halifax County real estate. Octavius was one of ten Wiggins children in his father's household. His oldest brother, 22 year old Blake was listed as a physician. Mason L. Wiggins owned 60 slaves in 1850. A decade later, 16 year old Octavius was still in his father's household and shown as having attended school that year. However, his father Mason had increased his real estate to $5935.00, and since personal property is also listed in the 1860 census we know that he owned $108,625.00. Of course, much of that personal property came in the form of the 68 people he owned.

When the Civil War broke out and North Carolina seceded, Wiggins was a student at the University of North Carolina. Wiggins originally enlisted as an 18 year old private in the 3rd North Carolina Cavalry on June 26, 1862. However, in January 1863, he transferred to Company E of the 37th North Carolina Infantry as a 2nd lieutenant. He fought in the Army of Northern Virginia's campaigns and received a wound during the 1864 Overland Campaign fighting. He was allowed a furlough home to recover. Wiggins returned to his unit during the Petersburg Campaign. While defending the earthwork line southwest of Petersburg on April 2, 1865, Wiggins was again wounded by a shot so close to his face that it grazed his scalp and the black powder from the rifle blast blinded him. He was quickly captured and held at City Point before being shipped off to Johnson's Island, Ohio, an officer's prison. While enroute by train, Wiggins jumped out of the box car and eventually made his way back home to Halifax County. Killed near him on April 2 was his captain, William T. Nicholson. Nicholson was a near neighbor of Wiggins before the war, a fellow UNC student, and came from a wealthy large slaveholding family, too.

After the war Wiggins moved to Wilmington, North Carolina. The 1870 census shows him and his wife Anna living with his in-laws, the Parsley family, and working as a supervisor at a saw mill. In 1900, Wiggins was still in Wilmington. The now 56 year old Wiggins was still in the lumber business. Wiggins died on November 27, 1908 in Madison County, Mississippi. He was 64 years old.

One wonders what Davis's and Wiggins's lives would turned out like if their early life situations some how could have been reversed.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)