The Southern Enterprise was under the editorship of William P. Price. Price is shown as a twenty-five year old lawyer in the 1860 census. He owned $4200 in real estate and $4450 in personal property. I found it interesting that the paper's motto was "Equal Rights to All."

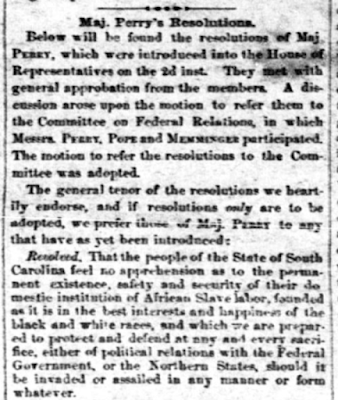

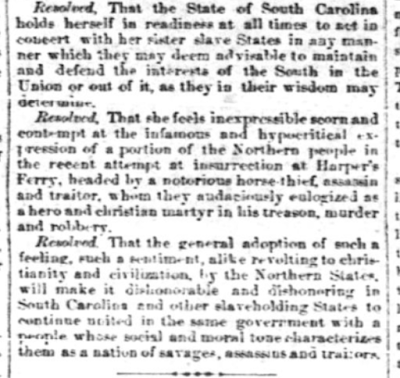

This set of resolutions by the South Carolina House of Representatives were passed in the wake of John Brown's hanging. Their sentiments were quite common across the slave states, especially at this time.

Continuing on John Brown, this short article discusses the Kentucky hemp rope used to hang John Brown. If you are a longtime reader of my "Random Thoughts," I've covered this particular item in a few past posts here, here, and here.

Cotton was indeed King in the South, especially in the Deep South. Cotton market prices were printed in almost each and every paper as ready reference. The production of the fiber funded the region's economy like nothing else, and obviously, its development depended almost entirely upon enslaved labor.

New tax regulations for the town of Greenville, South Carolina, in 1859, stated that those who wished to be excluded from area slave patrol duty must pay $2.50 to the town clerk.

Slavery provided jobs to more than planters and cotton factors. Young men, like that above, trying to get their start in the the world sought work as overseers on plantations.

Militia units, some of which went back years, but others that emerged in the wake of John Brown's raid, often advertised in newspapers for muster day events and when dues were late, as shown here. Militias served as ready military if a slave rebellion broke out. Many militias turned into companies for forming regiments when the Civil War came.

Who knew macaroni was available in upland South Carolina in 1859? I wonder if they had cheese with it? Yum!

Sales of slaves were commonly advertised in newspapers. At the time there were few better ways to get the word out about a pending sale. Nine slaves (here called servants) in a family, a man, his wife, and seven children, who were from six to twenty-two years old were offered. They were skilled workers, who kept house, cooked, ironed, sewed, and manufactured clothes.

Slaves needed clothes, and some masters found it more practical to purchase them rather than have his slave produce them. They also needed other basics. Here A. Sommer advertised to sell "a well-assorted Stock of Negro Clothing, Hats, Shoes and Blankets," which he offered "Low for cash."

Just about every product imaginable was marketed to planters. Here a patent medicine, Jacob's Cordial, is offered and which has saved 10,000 slaves per year. It claimed to be the "positive remedy" for dysentery, diarrhea, and flux (hemorrhoids). It only cost $1 per bottle. That's about $30 today.

Another research of interest of mine, black barbers, popped up in this edition. Two barbers, Wilson Cook and Burride, offered their hair cutting and shaving services. It appears that these men were enslaved barbers, as neither shows up in the 1860 census. However, there are about three or four free men of color who also worked in Greenville as barbers and who did show up on the 1860 census. It is fascinating to me that enslaved men's notices appear in newspapers. Perhaps their owners posted the advertisements, and also kept a good portion if not all of their earnings.