One of the things that often comes out

in Civil War soldier’s letters is the toll that military service took on one’s

body, mind, and spirit. Experiencing hard fighting, eating bad food, enduring

long marches, and living out in all types of weather wreaked havoc on men’s

physical and mental systems.

The Petersburg Campaign’s summer months

of 1864 were particularly trying. After almost a month of constant combat in

May and early June, the fighting transitioned to Petersburg for control of the

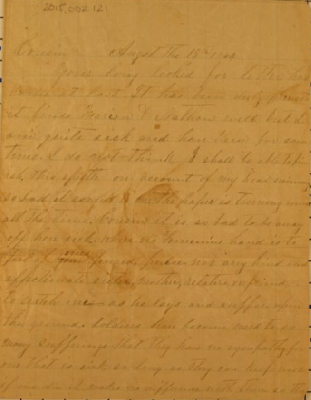

area’s roads and railroads. On August 18, 1864, Lt. Joseph G. Younger of

Company F, 53rd Virginia Infantry, sat down to write a letter to a

cousin. This letter is now in the collections of Pamplin Historical Park and

the National Museum of the Civil War Soldier. Younger opened by stating that he

had received his kinsman’s letter that he had “long looked for.”

Fighting in Company F with Younger were

his brothers, Francis Marion and Nathan B. Younger. He informed the recipient that

both of them were fine, but that he himself was not feeling well and had been

sick “for some time.” Younger gives the reader a hint of his symptoms. “I do

not think I shall be able to finish this epistle on account of my head swimming

so bad it seems to me the paper is turning ‘round all the time.” Perhaps

Younger was suffering from a high fever, or consequences of heat exhaustion.

Regardless, he ached for kind medical attention: “Cousin, it is so bad to be

away off here sick, where no feminine hand is to feel of one’s pulse, or any

kind and affectionate sister, mother, relative, or friend to watch one as he

lays and suffers upon the ground.”

Younger had enlisted in July 1861, and

over his three years of service had experienced many hardships and viewed

terrible sights on various battlefields. Soldiers often mentioned the callous

nature that built up over time. Younger mentioned it, too. “Soldiers here

become used to so many sufferings that they have no sympathy for one that is

sick, so long as they can keep well. If one dies it makes no difference with

them . . . . If one gets killed in battle it is the same case,” he wrote.

For a few lines—perhaps forcing his

thoughts in a more pleasant direction—Younger writes about some of the young

ladies back home and their current situations. However, soon he is right back

to his present experience, without even a transition. “There was terrible

shelling at Petersburg this morning before day. I have not heard the cause of

it. We will have hot times here soon I think. A good deal of sickness is

getting among our soldiers.”

With so much hardship to endure it is

easy to see how one might become somewhat disheartened. That sentiment comes

though: “I am in hopes the war will end soon. I have thought it would end this [past]

winter, but I do not know how it will end, nor when. I know this much; it

cannot end too soon for us. I think it has as well end this winter as to go on

next spring, for it will never end by fighting no-how.”

Younger’s last thoughts include a few

lines about facing African American Union soldiers in battle, or the “Yankee

negro,” as he termed them. “I think if they fight negroes against us, we ought

to conscript some of ours to meet them. I reckon our negroes will fight as well

as theirs,” Younger wrote. He concluded the letter much as he started it: “I

must close as I am getting so weak I cannot sit up. Write soon. I remain your

affectionate cousin.”

Younger transferred to an artillery unit

in December 1864 and survived the war. He died in Arkansas in 1916.

No comments:

Post a Comment