Tuesday, March 31, 2015

A Singer Family Tragedy

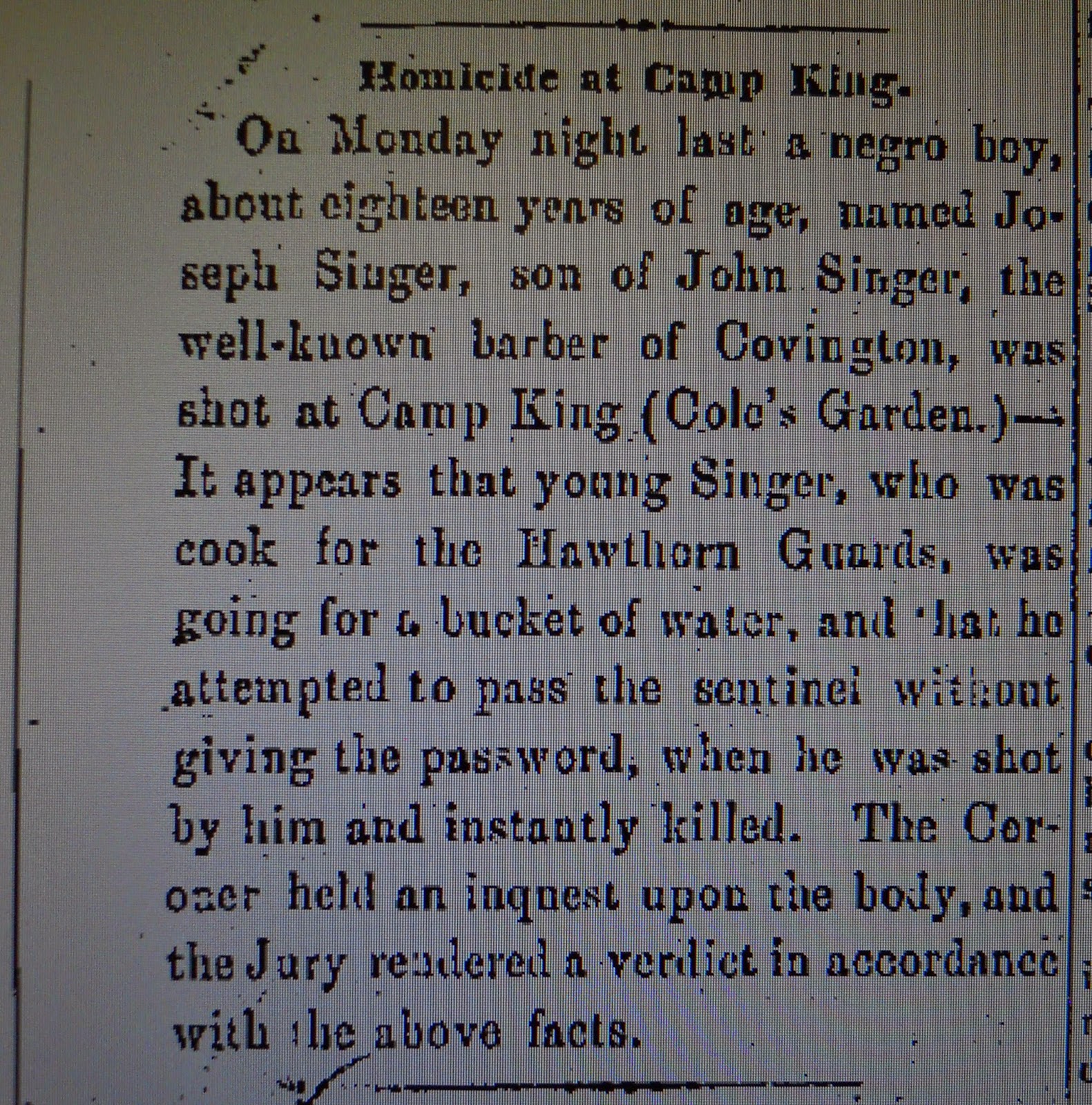

Yesterday I posted about Covington, Kentucky, African American barber John Singer. Singer utilized his skills as a barber to become an important part of his community although most free people of this era experienced racial prejudice at almost every turn. By entrepreneurship, thrift, and hard work Singer was able to provide well for his family. However, despite his many successes, Singer, like many other free blacks saw their fair share of tragedy, too.

I located this newspaper article in the September 28, 1861 edition of the Covington Journal, while searching for more information on John Singer for yesterday's post. This tragic incident occurred shorty after Kentucky declared their allegiance to the Union through their elected representatives in the state legislature.

Of course, at this time African Americans (whether slave or free) were unable to serve as soldiers in the Union army. Despite this fact, Kentucky blacks, again, both free and enslaved, served in forming Union units in various labor capacities. We do not know if John Singer was proud of his son Joseph in helping the Union cause as a cook, or if John Singer would have preferred his son stay away from the soldiers' encampment to prevent potential harassment or worse. Regardless, one can only image the heartbreak the "well-known barber" felt when he learned of his son's death at such a young age while only attempting to help.

Monday, March 30, 2015

John Singer - Covington Black Barber

Last week I was happy to be contacted by a good friend and colleague who is currently working on the Kentucky Civil War Governors Papers project. While doing transcriptions he came across a document that he knew would intrigue me.

The letter was written to Gov. Beriah Magoffin, and although it was undated, it had to have been written between the governor's election in 1859 and resignation in 1862. The missive was written by Samuel H. Cambron, a Covington, Kentucky, attorney, and was likely a customer of the subject of the letter, one John Singer, free man of color and noted barber.

I had come across Singer's name some time back in my research through the 1850 and 1860 censuses. In addition, I also had located an advertisement (above) that he ran for a time in the mid-1840s in the Licking Valley Register. Other than one of Singer's sons, Charles, he was the only black barber in Covington listed in those censuses. However, he competed for business with several immigrant barbers, mainly German, but also Irish and Italian. Singer though must have built up quite a large clientele, as he is listed as owning $4000 in real estate in 1860.

Singer had moved to Covington from western Virginia in 1836. Although it is not certain, he may have come from another river town like Wheeling. In an article that ran in the Covington Daily Commonwealth in the 1870s, he explained that his settlement as a free black man in Covington was first met with resistance, but he soon gained acceptance through his pleasant disposition and quality work.

In fact, Singer became such as asset to the community that he garnered enough support to get a legislative act passed that allowed him to stay in the state (see below) being that he was a free black man.

But back the the letter "To his Excellency" Governor Magoffin. In it the attorney Cambron explained that Singer and his wife Ann, and daughter, Rachel, and son, Charles, had been indicted for crossing the Ohio River, probably to Cincinnati, and then returning to Covington. Of course, the fear at this time in this activity would be that Singer might help runaways to freedom if allowed to do such.

However, Cambron explained to the governor that "John Singer & his family have [been] in the community for a long series of years say since 1836, [and] supported a good character. [He is] Industrious honest prudent and Saving. [He] Has made some money by his business (Barber) and so far as I know without reproach or suspicion of any citizen." Quite the endorsement.

Cambron went on to explain that Singer had come to Covington from Virginia in 1836 and that the state legislature had made an act authorizing the barber to live in Kentucky as a free man of color, and also that Singer had been accustomed to traveling across the Ohio River regularly before a recent law was passed disallowing free blacks to do so. Cambron claimed that "the violations which have occurred were not the result of design but of Mistake as the Extent of the rights conferred by the act for his benefit referred to above." Cambron requested that if the governor found it within his ability he "should deem it proper to pardon him and his wife and two children," and that if done "would meet with the approval of most citizens of this city who know the facts and know Singer & his said family."

Singer continued to work as a barber and apparently a number of this other sons also entered the trade. Free man of color John Singer died on December 6, 1886, and was buried in Highland Cemetery. His wife Ann followed in him death in 1893.

Sunday, March 29, 2015

Just Finished Reading - Moonshiners and Prohibitionists

I apologize again for my delays in making posts. I was in St. Augustine, Florida, last week for the National Council on History Education conference where I presented a couple of sessions. And unfortunately, I came back home with spring allergy symptoms that have made me not feel up to posting until today. I realize that I many of my recent posts have been book reviews, but I have some interesting things in the works and will be getting them up soon.

A few weeks ago a friend loaned me the movie Lawless, which chronicles a moonshine war that occurred in Franklin County, Virginia, in the 1930s. I had seen the previews for the film when it originally came out, but hadn't taken the time or effort to see it at the theater, find it online, or rent it. I have to say though, I really enjoyed it. Watching it made me curious to learn more about the struggle in the southern Appalachian Mountains between the moral, political, and economic implications that came with illegal alcohol.

I located Moonshiners and Prohibitionists: The Battle over Alcohol in Southern Appalachia (University Press of Kentucky, 2011) at my local library. Its author, Bruce E. Stewart, is a history professor at Appalachian State University, but was not there when I received my education.

Stewart focuses his research on this topic specifically to western North Carolina, but his finding could likely be generalized to most of the southern Appalachian region. I appreciated that Stewart took a long approach to his research into moonshining in that he showed that the practice has roots that go back to the first white settlers into the area in the late-eighteenth century. Steward claims that early distillers were not viewed so much as criminals as much as they were seen as entrepreneurs by their fellow citizens.

However, as alcohol manufacture in the southern Appalachians progressed into the antebellum era, and with its rise in demand, and thus its production, the backlash of temperance movements also emerged. The demands for food during the Civil War also impacted impressions of moonshiners. Corn, a favored and necessary ingredient in whiskey production, grew scarce during the war years. Citizens came to see moonshiners as using the grain for gain rather than helping feed mountain residents, thus causing some resentment.

When federal taxation began to be more strictly enforced during the Reconstruction era, a significant amount of violence emerged among revenue agents and mountain distillers intent on evading the taxes. Examining this particular subject allowed Stewart the opportunity to delve into the "Creation of the Myth of Violent Appalachia and its Consequences, 1878-1890," in chapter six. Industrialization and social dislocation had more to do the violence that emerged in the southern mountains during this era, but many, even some of those who lived there, saw alcohol as main contributor to the violence and started making pushes for its prohibition.

By 1908, North Carolina approved a referendum outlawing the sale and manufacture of alcohol within the state. However, like in other parts of the Union, the demand for illegal alcohol remained, and thus the profitability obtained through it production continued it manufacture - even after prohibition ended. The western North Carolina mountains proved especially advantageous to concealing production and hiding the product's movement to markets.

While Stewart ends the Moonshiners and Prohibitionists story in the 1920s, I think it would have made for an interesting epilogue to show how moonshining and bootlegging influenced the sport of stock car racing in the mid-twentieth century.

I really enjoyed reading Mooshiners and Prohibitionists and learned a lot about the conflict between rural and urban mountain areas over distilling and temperance during this period. I high recommend it for those who are also curious about the subject. On a scale of one to five, I give the book a 4.75.

A few weeks ago a friend loaned me the movie Lawless, which chronicles a moonshine war that occurred in Franklin County, Virginia, in the 1930s. I had seen the previews for the film when it originally came out, but hadn't taken the time or effort to see it at the theater, find it online, or rent it. I have to say though, I really enjoyed it. Watching it made me curious to learn more about the struggle in the southern Appalachian Mountains between the moral, political, and economic implications that came with illegal alcohol.

I located Moonshiners and Prohibitionists: The Battle over Alcohol in Southern Appalachia (University Press of Kentucky, 2011) at my local library. Its author, Bruce E. Stewart, is a history professor at Appalachian State University, but was not there when I received my education.

Stewart focuses his research on this topic specifically to western North Carolina, but his finding could likely be generalized to most of the southern Appalachian region. I appreciated that Stewart took a long approach to his research into moonshining in that he showed that the practice has roots that go back to the first white settlers into the area in the late-eighteenth century. Steward claims that early distillers were not viewed so much as criminals as much as they were seen as entrepreneurs by their fellow citizens.

However, as alcohol manufacture in the southern Appalachians progressed into the antebellum era, and with its rise in demand, and thus its production, the backlash of temperance movements also emerged. The demands for food during the Civil War also impacted impressions of moonshiners. Corn, a favored and necessary ingredient in whiskey production, grew scarce during the war years. Citizens came to see moonshiners as using the grain for gain rather than helping feed mountain residents, thus causing some resentment.

When federal taxation began to be more strictly enforced during the Reconstruction era, a significant amount of violence emerged among revenue agents and mountain distillers intent on evading the taxes. Examining this particular subject allowed Stewart the opportunity to delve into the "Creation of the Myth of Violent Appalachia and its Consequences, 1878-1890," in chapter six. Industrialization and social dislocation had more to do the violence that emerged in the southern mountains during this era, but many, even some of those who lived there, saw alcohol as main contributor to the violence and started making pushes for its prohibition.

By 1908, North Carolina approved a referendum outlawing the sale and manufacture of alcohol within the state. However, like in other parts of the Union, the demand for illegal alcohol remained, and thus the profitability obtained through it production continued it manufacture - even after prohibition ended. The western North Carolina mountains proved especially advantageous to concealing production and hiding the product's movement to markets.

While Stewart ends the Moonshiners and Prohibitionists story in the 1920s, I think it would have made for an interesting epilogue to show how moonshining and bootlegging influenced the sport of stock car racing in the mid-twentieth century.

I really enjoyed reading Mooshiners and Prohibitionists and learned a lot about the conflict between rural and urban mountain areas over distilling and temperance during this period. I high recommend it for those who are also curious about the subject. On a scale of one to five, I give the book a 4.75.

Tuesday, March 17, 2015

Park Day is Coming Soon - Help History, Help Out

DON’T TAKE HISTORY FOR GRANTED: JOIN CIVIL WAR TRUST FOR NATIONAL PARK DAY EVENT

Now in its 19th year, Park Day is a hands-on preservation event to clean up and restore America’s hallowed Civil War and Revolutionary War sites.

(Washington, D.C.) You can give back to your country, get out of the house, and honor your heritage all at once on by joining the Civil War Trust on Saturday, March 28, for Park Day 2015. Park Day is an annual hands-on preservation event to help maintain Civil War — and now Revolutionary War — battlefields and historic sites across the nation.

For the 19th straight year, history buffs, community leaders, preservationists and other volunteers will fan out across 108 historic sites in 29 states for a spring cleanup at America’s battlefields and historic sites. Armed with trash bags, rakes, weed whackers and paint brushes, this corps of community-minded citizens can use your help in sprucing up these national treasures.

This year, for the first time, the Trust adds Revolutionary War battlefields to Park Day as part of the Trust’s new “Campaign 1776” initiative to save the battlefields of the American Revolution and War of 1812. From Gettysburg to Guilford Court House, and Saratoga to Shiloh, Park Day participants will tackle maintenance tasks large and small.

“Park Day volunteers are critically important to historic sites that must balance basic maintenance needs with limited budgets and small staffs,” said Civil War Trust President James Lighthizer. “Neglect and deferred repairs can be as much a threat to historic sites as development. Visitors really do notice the difference after our legions of volunteers pitch in and clean up!”

Since 1996, thousands of volunteers of all ages and abilities, including Boy Scouts, Rotarians, Lions Club members, church groups, ROTC units, youth groups and many others, have taken part in Park Day.

Besides picking up trash, activities can include building trails, raking leaves, painting signs, putting up fences and other tasks. In addition to the satisfaction that volunteer work brings, participants receive official Park Day t-shirts and have an opportunity to hear local historians describe the significance of the participating site.

In 2014, nearly 9,000 volunteers converged on 104 sites across the country, where they donated more than 35,000 service hours. With your help, we can do even more this year. Every trash bag that goes to the dump, every fence that is painted and every tree that is planted, leaves each site that much better prepared for the tourists who will visit this year to experience their heritage where it happened.

Keeping America’s hallowed grounds pristine is a fitting tribute not only to those who served in the early conflicts of American history, but to all soldiers who serve and protect our country. These preserved historic sites are outdoor classrooms, teaching young and old alike about the sacrifices made to forge this nation. For a complete list of participating Park Day sites, visitwww.civilwar.org/parkday.

The Civil War Trust is the largest and most effective nonprofit organization devoted to the preservation of America’s hallowed battlegrounds. Although primarily focused on the protection of Civil War battlefields, through its Campaign 1776 initiative, the Trust also seeks to save the battlefields connected to the Revolutionary War and War of 1812. To date, the Trust has preserved more than 40,800 acres of battlefield land in 20 states. Learn more atwww.civilwar.org.

###

(To learn more about the 108 participating Park Day sites, visit www.civilwar.org/parkday).

Now in its 19th year, Park Day is a hands-on preservation event to clean up and restore America’s hallowed Civil War and Revolutionary War sites.

(Washington, D.C.) You can give back to your country, get out of the house, and honor your heritage all at once on by joining the Civil War Trust on Saturday, March 28, for Park Day 2015. Park Day is an annual hands-on preservation event to help maintain Civil War — and now Revolutionary War — battlefields and historic sites across the nation.

For the 19th straight year, history buffs, community leaders, preservationists and other volunteers will fan out across 108 historic sites in 29 states for a spring cleanup at America’s battlefields and historic sites. Armed with trash bags, rakes, weed whackers and paint brushes, this corps of community-minded citizens can use your help in sprucing up these national treasures.

This year, for the first time, the Trust adds Revolutionary War battlefields to Park Day as part of the Trust’s new “Campaign 1776” initiative to save the battlefields of the American Revolution and War of 1812. From Gettysburg to Guilford Court House, and Saratoga to Shiloh, Park Day participants will tackle maintenance tasks large and small.

“Park Day volunteers are critically important to historic sites that must balance basic maintenance needs with limited budgets and small staffs,” said Civil War Trust President James Lighthizer. “Neglect and deferred repairs can be as much a threat to historic sites as development. Visitors really do notice the difference after our legions of volunteers pitch in and clean up!”

Since 1996, thousands of volunteers of all ages and abilities, including Boy Scouts, Rotarians, Lions Club members, church groups, ROTC units, youth groups and many others, have taken part in Park Day.

Besides picking up trash, activities can include building trails, raking leaves, painting signs, putting up fences and other tasks. In addition to the satisfaction that volunteer work brings, participants receive official Park Day t-shirts and have an opportunity to hear local historians describe the significance of the participating site.

In 2014, nearly 9,000 volunteers converged on 104 sites across the country, where they donated more than 35,000 service hours. With your help, we can do even more this year. Every trash bag that goes to the dump, every fence that is painted and every tree that is planted, leaves each site that much better prepared for the tourists who will visit this year to experience their heritage where it happened.

Keeping America’s hallowed grounds pristine is a fitting tribute not only to those who served in the early conflicts of American history, but to all soldiers who serve and protect our country. These preserved historic sites are outdoor classrooms, teaching young and old alike about the sacrifices made to forge this nation. For a complete list of participating Park Day sites, visitwww.civilwar.org/parkday.

The Civil War Trust is the largest and most effective nonprofit organization devoted to the preservation of America’s hallowed battlegrounds. Although primarily focused on the protection of Civil War battlefields, through its Campaign 1776 initiative, the Trust also seeks to save the battlefields connected to the Revolutionary War and War of 1812. To date, the Trust has preserved more than 40,800 acres of battlefield land in 20 states. Learn more atwww.civilwar.org.

###

(To learn more about the 108 participating Park Day sites, visit www.civilwar.org/parkday).

Monday, March 9, 2015

Just Finished Reading - War Upon the Land

As you can see I have been on quite the reading spree. I guess that is one positive from all the snow and cold weather. However, I will be happy to see all of this white stuff melt away.

My latest read was published a couple of years ago, and was another selection I had on my "Wish List." War Upon the Land: Military Strategy and the Transformation of Southern Landscapes during the American Civil War, by Lisa M. Brady (UGA Press, 2012) examines yet another fascinating aspect of the war (as an environmental study) that has not received much attention before it appeared, but is now producing more works.

To show how the Union army used and attempted to change nature and the southern environment, Brady focused on three campaigns: the Vicksburg campaign, Sherman's march through Georgia and the Carolinas, and the 1864 Shenandoah Valley campaign. By looking at these campaigns Brady shows how war was made, not only on the various Confederate forces that the Union army encountered, but also on the "agroecological" environments where these campaigns played out.

In the Vicksburg campaign Grant determined to "use every means to weaken the enemy, by destroying their means of subsistence, withdrawing their means of cultivating their fields, and in every other way possible." To do so the Union army embraced a mode of destroying crops and the ability to grown more crops, encouraged slaves to come into Union lines in order to have them supply additional labor and deprive that labor from the Confederates, which in turn undermined "the local residents' (and, by association, the Confederate government's) control over the natural environment." Grant even attempted an enormous canal project that tried to alter the landscape in order to help the Union army achieve victory. And although the canal project failed, a invaluable Union victory was realized at Vicksburg through Grant's method of warfare.

Similarly, and again with Grant's vision, first Gen. Hunter and then Gen. Sheridan reeked havoc in the Shenandoah Valley during the summer and fall of 1864. The Valley was a granary for the Confederacy, its wheat, oats, and other grains fed the soldiers, their animals, and those on the home front. The Union forces in the Valley did tremendous damage to its landscape. And although it was not literally turned into a desert and wasteland as many of the residents described it, its damage and loss proved costly economically, militarily, and politically. Nineteenth century Valley dwellers had worked hard (along with their slaves) to turn the region from an unmitigated "wilderness" into an agricultural paradise, but the Union army's burning and damaging ways reversed those efforts, for at least a time.

Finally, what is fact and what is fiction of Sherman's March to the Sea and beyond has been the subject of debate since those events happened, but it cannot be doubted that some the most significant damage of the war was taken out on Georgia and South Carolina in 1864 and 1865. Again, under the direction of Grant, Sherman carried out the work. Thousands and thousand of slaves, whose labor had brought wealth and prosperity to southern citizens, were liberated, which made recovering from Sherman's bummers a true task. In addition, Sherman's severing of his force from his lines of supply caused his men to live off the land, taking subsistence from those who had it and leaving them with little to nothing. Those in the way simply got washed over like a tsunami. Homes, towns, and crops were burned breaking the will of the people to oppose him and thus helped speed the end of the war.

While this mode of warfare proved successful, it obviously brought an enormous amount of physical and psychological damage to those who suffered through it. One of the things I appreciated about War Upon the Land, was Brady's inclusion of the accounts of those not only doing the damage to the South's environment, but also those whose worlds were damaged. For many, perceived antebellum order was turned to wartime chaos and confusion.

War Upon the Land is a significant addition to Civil War studies. And as mentioned, its groundbreaking look at the environmental aspect of the war is already producing more scholarship. Explaining the details of the various methods of warfare and its impact on the South's people and environment are valuable contributions to the field. On a scale of one to five, I give War Upon the Land a 4.5.

My latest read was published a couple of years ago, and was another selection I had on my "Wish List." War Upon the Land: Military Strategy and the Transformation of Southern Landscapes during the American Civil War, by Lisa M. Brady (UGA Press, 2012) examines yet another fascinating aspect of the war (as an environmental study) that has not received much attention before it appeared, but is now producing more works.

To show how the Union army used and attempted to change nature and the southern environment, Brady focused on three campaigns: the Vicksburg campaign, Sherman's march through Georgia and the Carolinas, and the 1864 Shenandoah Valley campaign. By looking at these campaigns Brady shows how war was made, not only on the various Confederate forces that the Union army encountered, but also on the "agroecological" environments where these campaigns played out.

In the Vicksburg campaign Grant determined to "use every means to weaken the enemy, by destroying their means of subsistence, withdrawing their means of cultivating their fields, and in every other way possible." To do so the Union army embraced a mode of destroying crops and the ability to grown more crops, encouraged slaves to come into Union lines in order to have them supply additional labor and deprive that labor from the Confederates, which in turn undermined "the local residents' (and, by association, the Confederate government's) control over the natural environment." Grant even attempted an enormous canal project that tried to alter the landscape in order to help the Union army achieve victory. And although the canal project failed, a invaluable Union victory was realized at Vicksburg through Grant's method of warfare.

Similarly, and again with Grant's vision, first Gen. Hunter and then Gen. Sheridan reeked havoc in the Shenandoah Valley during the summer and fall of 1864. The Valley was a granary for the Confederacy, its wheat, oats, and other grains fed the soldiers, their animals, and those on the home front. The Union forces in the Valley did tremendous damage to its landscape. And although it was not literally turned into a desert and wasteland as many of the residents described it, its damage and loss proved costly economically, militarily, and politically. Nineteenth century Valley dwellers had worked hard (along with their slaves) to turn the region from an unmitigated "wilderness" into an agricultural paradise, but the Union army's burning and damaging ways reversed those efforts, for at least a time.

Finally, what is fact and what is fiction of Sherman's March to the Sea and beyond has been the subject of debate since those events happened, but it cannot be doubted that some the most significant damage of the war was taken out on Georgia and South Carolina in 1864 and 1865. Again, under the direction of Grant, Sherman carried out the work. Thousands and thousand of slaves, whose labor had brought wealth and prosperity to southern citizens, were liberated, which made recovering from Sherman's bummers a true task. In addition, Sherman's severing of his force from his lines of supply caused his men to live off the land, taking subsistence from those who had it and leaving them with little to nothing. Those in the way simply got washed over like a tsunami. Homes, towns, and crops were burned breaking the will of the people to oppose him and thus helped speed the end of the war.

While this mode of warfare proved successful, it obviously brought an enormous amount of physical and psychological damage to those who suffered through it. One of the things I appreciated about War Upon the Land, was Brady's inclusion of the accounts of those not only doing the damage to the South's environment, but also those whose worlds were damaged. For many, perceived antebellum order was turned to wartime chaos and confusion.

War Upon the Land is a significant addition to Civil War studies. And as mentioned, its groundbreaking look at the environmental aspect of the war is already producing more scholarship. Explaining the details of the various methods of warfare and its impact on the South's people and environment are valuable contributions to the field. On a scale of one to five, I give War Upon the Land a 4.5.

Friday, March 6, 2015

Just Finished Reading - Milliken's Bend

All of the snow and cold weather we have been experiencing here in Kentucky has really cut down on my walking regimen, but conversely it has increased my reading time.

In an attempt to knock out some of my own books on my "to be read shelf" I had not been to my local public library in quite a while. A couple of weeks ago I decided to take a few minutes to browse through their online catalog and I saw a couple of selections that they had recently added that piqued my interest.

One of those books was Milliken's Bend: A Civil War Battle in History and Memory, by Linda Barnickel (LSU Press, 2012). I had had this book on my Amazon.com "wish list" since it came out, so I was happy to get to check it out for free.

Barnickel provides a full treatment on this Louisiana battle which was part of the Vicksburg Campaign. In the engagement a recently recruited Union force made up primarily of former slaves was attacked by Texas Confederates under the command of Gen. Henry McCulloch on June 7, 1863.

This was one of the first battles in which black troops engaged in combat. Milliken's Bend along with the previously fought Port Hudson, also in Louisiana, and Battery Wagner in South Carolina, were used by the northern press to help convince those that were skeptical that former slaves would indeed prove effective in combat.

After the black troops had participated in a brief reconnaissance toward Richmond, Louisiana, on June 6, they returned to their Milliken's Bend camp. In the battle the Texans surprised the black troops by attacking and drove them back to the edge of the Mississippi River. The fighting turned desperate and resulted in terrific losses for the black troops who had just joined the Union army only a few weeks before. The African Americans and part of the white 23rd Iowa finally held with the help of levee defenses constructed partly of cotton bales,and the aid of Union gunboats on the river. The battle featured deadly hand-to-hand combat where muskets battered skulls and bayonets were wielded freely on both sides.

Due largely to the Union gunboats' assistance, the southerners retreated, taking a number of captured black troops and their white officers. Rumors of the murder of black troops and some of the white officers made headlines in the press. Although it is difficult to determine the veracity of these reports it does appear that some the African American solders were executed after surrender (as happened in several other engagements in the war) and that at least two of the white officers were later killed for leading the black troops at Milliken's Bend.

Barnickel shows the importance of reconsidering this largely forgotten battle and how it influenced northern opinion on the use of former slaves as soldiers. In the battle's aftermath, the rumors of mistreatment of the black soldiers helped lead to a breakdown in prisoner exchanges, and the example of the Milliken's Bend soldiers steeled other black recruits and units to join in and continue their fight for freedom.

Of particular interest to me was book's first chapter "The Dark Pall of Barbarism: Emancipation as a War Crime." This chapter examined the prewar perceptions of slaves by whites in the northern Louisiana, eastern Texas region. It really fit in well with much of what Woodward had explained in my previous read, Marching Masters. The Texans especially saw blacks as somewhat similar to the Native Americans they had to contend with on what was still then the frontier border. Slaves were viewed as merely tempered savages that had been tamed under by the influence of the institution and the guidance of their owners. The Texans and Louisianans, like most other southerner, believed that if their slaves were emancipated ruin would come to the white agricultural world, their way of life would be gone forever, and eventually they would be forced to relocated or exterminate the blacks as they had the Indians.

On a scale of one to five, I give Milliken's Bend a 4.75. It is a well researched and written work that helps shed new light on a largely forgotten but yet important engagement.

In an attempt to knock out some of my own books on my "to be read shelf" I had not been to my local public library in quite a while. A couple of weeks ago I decided to take a few minutes to browse through their online catalog and I saw a couple of selections that they had recently added that piqued my interest.

One of those books was Milliken's Bend: A Civil War Battle in History and Memory, by Linda Barnickel (LSU Press, 2012). I had had this book on my Amazon.com "wish list" since it came out, so I was happy to get to check it out for free.

Barnickel provides a full treatment on this Louisiana battle which was part of the Vicksburg Campaign. In the engagement a recently recruited Union force made up primarily of former slaves was attacked by Texas Confederates under the command of Gen. Henry McCulloch on June 7, 1863.

This was one of the first battles in which black troops engaged in combat. Milliken's Bend along with the previously fought Port Hudson, also in Louisiana, and Battery Wagner in South Carolina, were used by the northern press to help convince those that were skeptical that former slaves would indeed prove effective in combat.

After the black troops had participated in a brief reconnaissance toward Richmond, Louisiana, on June 6, they returned to their Milliken's Bend camp. In the battle the Texans surprised the black troops by attacking and drove them back to the edge of the Mississippi River. The fighting turned desperate and resulted in terrific losses for the black troops who had just joined the Union army only a few weeks before. The African Americans and part of the white 23rd Iowa finally held with the help of levee defenses constructed partly of cotton bales,and the aid of Union gunboats on the river. The battle featured deadly hand-to-hand combat where muskets battered skulls and bayonets were wielded freely on both sides.

Due largely to the Union gunboats' assistance, the southerners retreated, taking a number of captured black troops and their white officers. Rumors of the murder of black troops and some of the white officers made headlines in the press. Although it is difficult to determine the veracity of these reports it does appear that some the African American solders were executed after surrender (as happened in several other engagements in the war) and that at least two of the white officers were later killed for leading the black troops at Milliken's Bend.

Barnickel shows the importance of reconsidering this largely forgotten battle and how it influenced northern opinion on the use of former slaves as soldiers. In the battle's aftermath, the rumors of mistreatment of the black soldiers helped lead to a breakdown in prisoner exchanges, and the example of the Milliken's Bend soldiers steeled other black recruits and units to join in and continue their fight for freedom.

Of particular interest to me was book's first chapter "The Dark Pall of Barbarism: Emancipation as a War Crime." This chapter examined the prewar perceptions of slaves by whites in the northern Louisiana, eastern Texas region. It really fit in well with much of what Woodward had explained in my previous read, Marching Masters. The Texans especially saw blacks as somewhat similar to the Native Americans they had to contend with on what was still then the frontier border. Slaves were viewed as merely tempered savages that had been tamed under by the influence of the institution and the guidance of their owners. The Texans and Louisianans, like most other southerner, believed that if their slaves were emancipated ruin would come to the white agricultural world, their way of life would be gone forever, and eventually they would be forced to relocated or exterminate the blacks as they had the Indians.

On a scale of one to five, I give Milliken's Bend a 4.75. It is a well researched and written work that helps shed new light on a largely forgotten but yet important engagement.

Tuesday, March 3, 2015

Just Finished Reading - Marching Masters

Upon reading a new take on an old subject, I have often asked myself, "Why hasn't someone looked at this before?" It all seems so clear once it has been presented, but, of course, that's after the fact. It takes someone with foresight to break new ground.

Slavery, and thus race, have been examined in many studies, but Marching Masters: Slavery, Race, and the Confederate Army during the Civil War (Univ. Virginia Press, 2014), by Colin Edward Woodward, is the first book I can remember that offers such a solid and clear argument on how the institution influenced not only soldiers' motivations, but also the Confederate government's policies.

Woodward puts forth the fact that while the majority of Confederate soldiers did not own slaves, they lived in a society and economy that derived its lifeblood from the labor of human property. The book's first chapter "The Question of Slavery - Confederate Soldiers and the Southern Cause, 1861-1862," spells this out. Southerners believed that the election of Abraham Lincoln and the Republican Party, which was wedded to the idea of the non-extension of slavery meant an eventual and certain death to the institution. And, whether soldiers claimed they went off to fight for adventure, defense of their homes, and "states' rights," all those ideas were upheld by a new country that made clear in its constitution that slavery would be at its foundation.

Marching Masters also looks into the relationship between enlisted men and officers, and thus how class divisions often played out in the Confederate army. Woodward contends that slavery was a bond that held an otherwise socially divided army together. Many of the officers were either slaveholders or came from slaveholding families and solders aspired to be like their officers inside the army and out.

One of the most interesting subjects covered in the book was the role of blacks in the Confederate army. Whether they were used to build fortifications, roads, and railroads, or labored as cooks, teamsters, and body servants in the army camps, slaves provided vital labor for the southern cause. And whether impressed by the government or brought by owners to the front, challenges arose that made civilian masters and soldiers think in news ways about the institution. African American labor allowed an enormous amount of white southerners to fight in the ranks. But when blacks ran off to nearby Union units or found ways around doing their required work, it tested antebellum conventions. Until very late in the war many Confederates believed that slavery could be saved and abolitionist gains since the Emancipation Proclamation could be overturned.

Encounters in combat between Confederate soldiers and black Union soldiers also figures into this study. This unpleasant reality meant that many southern soldiers would massacre black troops rather than see them taken captive. Much in these tragic episodes have roots that go back to antebellum fears of slave insurrections. In several battles black troops proved to be viewed as severe threats and received no quarter along with their white officers. Certainly not all captured USCT soldiers were killed nor their officers, but it was Confederate policy to turn over captured blacks to states to be dealt with as their laws prescribed. Some were returned to their former owners, while others were turned over to work for the Confederate army, and some were held in Confederate prisoner of war camps.

Of course, late in the war slaves became the topic of extensive discussions as to whether they could be made into Confederate soldiers and help fight for their continued enslavement. After debate the Confederate government decided they could, but they would not receive their freedom for their enlistment, and the policy went into effect so late tin the war that their impact was virtually nonexistent. And while some white soldiers supported the idea, just as many if not more were reviled by the idea.

Marching Masters is an important book that is changing what we thought we knew about Confederate soldiers. Woodward sums things up nicely by explaining the confusing nature of southerners' thoughts on blacks: "In the nineteenth century, white Southerners created a racial world-view that contained paradoxical tenets: blacks were lazy, but they formed the foundation of a social and economic 'mud sill' class; slaves were 'savages,' but the rarely revolted and were malleable to discipline; they were not intelligent enough to raise above being field hands, but they were clever enough to make laws that subjugated the South during Reconstruction. Black people were faithful hiders of silverware, yet they were prone to resistance and running away. They were both human and property, beloved family members and 'aliens,' Africans and Americans, heathens and Christians." Such misunderstandings have unfortunately been passed from generation to generation and although much has changed, much still remains to be done in the present to ensure a better future.

On a five point scale, I give Marching Masters a 4.75. I highly recommend this important new study and the perspective it shares.

Slavery, and thus race, have been examined in many studies, but Marching Masters: Slavery, Race, and the Confederate Army during the Civil War (Univ. Virginia Press, 2014), by Colin Edward Woodward, is the first book I can remember that offers such a solid and clear argument on how the institution influenced not only soldiers' motivations, but also the Confederate government's policies.

Woodward puts forth the fact that while the majority of Confederate soldiers did not own slaves, they lived in a society and economy that derived its lifeblood from the labor of human property. The book's first chapter "The Question of Slavery - Confederate Soldiers and the Southern Cause, 1861-1862," spells this out. Southerners believed that the election of Abraham Lincoln and the Republican Party, which was wedded to the idea of the non-extension of slavery meant an eventual and certain death to the institution. And, whether soldiers claimed they went off to fight for adventure, defense of their homes, and "states' rights," all those ideas were upheld by a new country that made clear in its constitution that slavery would be at its foundation.

Marching Masters also looks into the relationship between enlisted men and officers, and thus how class divisions often played out in the Confederate army. Woodward contends that slavery was a bond that held an otherwise socially divided army together. Many of the officers were either slaveholders or came from slaveholding families and solders aspired to be like their officers inside the army and out.

One of the most interesting subjects covered in the book was the role of blacks in the Confederate army. Whether they were used to build fortifications, roads, and railroads, or labored as cooks, teamsters, and body servants in the army camps, slaves provided vital labor for the southern cause. And whether impressed by the government or brought by owners to the front, challenges arose that made civilian masters and soldiers think in news ways about the institution. African American labor allowed an enormous amount of white southerners to fight in the ranks. But when blacks ran off to nearby Union units or found ways around doing their required work, it tested antebellum conventions. Until very late in the war many Confederates believed that slavery could be saved and abolitionist gains since the Emancipation Proclamation could be overturned.

Encounters in combat between Confederate soldiers and black Union soldiers also figures into this study. This unpleasant reality meant that many southern soldiers would massacre black troops rather than see them taken captive. Much in these tragic episodes have roots that go back to antebellum fears of slave insurrections. In several battles black troops proved to be viewed as severe threats and received no quarter along with their white officers. Certainly not all captured USCT soldiers were killed nor their officers, but it was Confederate policy to turn over captured blacks to states to be dealt with as their laws prescribed. Some were returned to their former owners, while others were turned over to work for the Confederate army, and some were held in Confederate prisoner of war camps.

Of course, late in the war slaves became the topic of extensive discussions as to whether they could be made into Confederate soldiers and help fight for their continued enslavement. After debate the Confederate government decided they could, but they would not receive their freedom for their enlistment, and the policy went into effect so late tin the war that their impact was virtually nonexistent. And while some white soldiers supported the idea, just as many if not more were reviled by the idea.

Marching Masters is an important book that is changing what we thought we knew about Confederate soldiers. Woodward sums things up nicely by explaining the confusing nature of southerners' thoughts on blacks: "In the nineteenth century, white Southerners created a racial world-view that contained paradoxical tenets: blacks were lazy, but they formed the foundation of a social and economic 'mud sill' class; slaves were 'savages,' but the rarely revolted and were malleable to discipline; they were not intelligent enough to raise above being field hands, but they were clever enough to make laws that subjugated the South during Reconstruction. Black people were faithful hiders of silverware, yet they were prone to resistance and running away. They were both human and property, beloved family members and 'aliens,' Africans and Americans, heathens and Christians." Such misunderstandings have unfortunately been passed from generation to generation and although much has changed, much still remains to be done in the present to ensure a better future.

On a five point scale, I give Marching Masters a 4.75. I highly recommend this important new study and the perspective it shares.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)