Today marks the 157th anniversary of the attack on Battery Wagner by the famous 54th Massachusetts Infantry. That action, depicted at the end of the motion picture Glory, brought much needed army and public attention to the important combat role that United States Colored Troops could play in the Civil War. In honor of the men who fought so courageously at Battery Wagner, I thought I would share a post that has an association to that engagement, and which I had not fully explored until this week.

When I worked for the Kentucky Historical Society, I had the pleasure of assisting with a Teaching American History Grant known as "Democratic Visions: From Civil War to Civil Rights." During the grant we were able to share with the participating teachers the power of place when teaching history.

One of the many historic sites that we visited was African American Cemetery #2 in Lexington. This burial ground served as the resting place for many of the community's notable black men and women from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when cemeteries were segregated. Those buried there included a number of USCT soldiers. As one might expect, the vast majority served in regiments raised in the Bluegrass State. Kentucky was second only to Louisiana in the number of men who served in African American regiments during the Civil War. That is pretty impressive when one considers that Kentucky, a loyal slave holding state, was allowed to delay USCT enlistments until the spring of 1864.

However, while we walked around the cemetery, a particular headstone caught my attention, so I snapped a picture. The inscription reads:

G. T. PROSSER

Co. D

54 MASS. INF.

I knew that several men who ultimately served in both the 54th and 55th Massachusetts regiments were noted as being born in Kentucky on their enlistment forms, so I assumed that was the case here. My line of thinking went something like this: A young man ran away from enslavement, made his way to a free states community, and when the opportunity came around, he enlisted to fight to end slavery, claim citizenship, and preserve the Union. However, I wanted to know for sure. I promised myself to find out the story of Mr. Prosser when I got the chance. Well, I forgot I had taken that photograph and it got buried behind hundreds of images on my digital camera. Since then, I've gone primarily to using my phone for photographs and the digital camera got put away. Long story short, I came across the headstone image recently and decided to look up his story now that I have ready access to soldiers' compiled service records and census records.

The story was much different than I expected. The first record I found on George Thomas Prosser was his compiled service records on Fold3.com. It tells that he was born in Columbia, Pennsylvania. Strike number one on my assumption. Being that he was a free man of color, I switched for a minute to Ancestry.com to look up census information. He was 21 years old when he enlisted in 1863, so he would hopefully appear in both the 1850 and 1860 census reports.

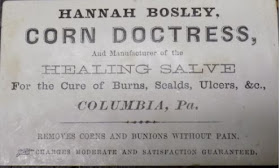

I did not find Prosser in the 1850 census, but I did in the 1860 listings. He is shown as an 18 year old black male in the household of Hannah Bosley (48, mulatto, doctress), who is Prosser's mother. She was born in Maryland. Also listed in household is Harriet Prosser (17), Mary Prosser (13), Isaac Prosser (13), and Sarah Prosser (7). All of the children were born in Pennsylvania.

Moving back to Prosser's service records, they give a cursory physical description: 21 years old, brown complexion, 6 feet tall. His occupation before enlisting in Company D was "laborer." Prosser enlisted on March 19, 1863 in Readville, Massachusetts for three years.

Only about four months in service, Pvt. Prosser's July-August 1863 card indicates he was absent. Further information at the bottom explains his absence. It reads "missing in action since July 18, 1863." That, of course, was the 54th's fight at Battery Wagner. The subsequent cards all state that he was absent, until the September-October card, which says Prosser was a "Prisoner of War in Charleston, S.C." From the records it appears that Pvt. Prosser was paroled and exchanged on March 4, 1865, and rejoined the 54th on June 7, 1865.

In Prosser's collection of records there is a letter dated December 3, 1863, from the Supervisory Committee Recruiting Colored Regiments in Philadelphia to Colonel Edward Hallowell, who followed Robert Gould Shaw as commander of the 54th after Gould's death at Battery Wagner. In the letter it mentions that Prosser's mother called at the Philadelphia office seeking information about her son. The writer said that it was reported that Prosser was killed on July 29 and he wished for information so that he could write her. No response letter from Hallowell is included. Perhaps Hallowell did not have any information at that point to share.

Pvt. Prosser's service records are silent as to the details about his time as a prisoner. First of all he was fortunate to be captured and not executed or sold into slavery, which were both not uncommon practices by Confederate captors. Perhaps he was able to convince the rebel authorities that he was a free man of color before the war.

A small clue to Prosser's release is given in Douglass R. Egerton's excellent 2016 book Thunder at the Gates: The Black Regiments that Redeemed America. Edgerton explains that the 21st USCT entered a fallen Charleston on February 18, 1865. The 55th Massachusetts entered the "Cradle of Secession" two days later. The 54th Massachusetts arrived On February 27. A company of the African American soldiers (Edgerton is not clear from which regiment) went to the city's Workhouse and found four members of the 54th Massachusetts, one of whom was Pvt. Prosser, nineteen months after his capture. Egerton writes "Much to everyone's surprise, the four were in reasonably good health and able to join their companies." It seems strange that Prosser would be noted as paroled and exchanged in his service records if he was indeed rescued from confinement by his comrades.

A lucky internet search find turned up a fascinating 1900 record (see below) from one of Prosser's comrades, lifelong friend and fellow native of Columbia, Sylvester Burrell, that gave some additional information on Prosser's POW treatment. It says that when Prosser returned to the unit he was missing his two upper front teeth "which he told me had been kicked out by a Rebel." Burrell also mentioned that Prosser told him "that he contracted the scurvy while a prisoner of war."

Regardless, Pvt. Prosser survived his incarceration and mustered out with the 54th on August 20, 1865, in Charleston.

George Thomas Prosser returned to Columbia, Pennsylvania after his service. The 1870 census shows him as a "day laborer" and living with his mother. He married, divorced, and then remarried. Prosser would become an African Methodist Episcopal minister. He eventually moved to Lexington, Kentucky to serve a church there and died of pneumonia at age 62 on July 3, 1904, and was buried in the African American Cemetery #2. A memorial marker is also in Zion Hill Cemetery in Prosser's hometown of Columbia, Pennsylvania.

Well, I feel that I know Mr. G. T. Prosser better now. Discovering the story of his military service and the sacrifice of his health as a prisoner of war makes me wish I had tried harder to learn his story much earlier.

No comments:

Post a Comment