My musings on American, African American, Southern, Civil War, Reconstruction, and Public History topics and books.

Friday, August 31, 2018

Just Finished Reading - Secessionists and Other Scoundrels: Selections from Parson Brownlow's Book

Polarizing historical personalities usually make for some interesting reading. And few were as polarizing as Knoxville newspaper editor and Methodist minister, William G. Brownlow. With Secessionists and Other Scoundrels: Selections from Parson Brownlow's Book, edited by Stephen V. Ash, we see him in all his polarizing glory.

Born in Wythe County, Virginia in 1805 and orphaned by age 11, Brownlow eventually settled in East Tennessee, as circuit riding Methodist preacher and starting newspapers in Elizabethton, Jonesboro, and finally Knoxville. A strict Whig, who viewed Henry Clay as the ideal statesman, and who possessed an unconditional Unionist sentiment, Brownlow would find himself in deep trouble when Tennessee seceded by majority referendum on June 9, 1861. Yet he would not yield his commitment for the Union. While votes in West and Middle Tennesse combined in favor of leaving the Union, East Tennessee voted to remain by a wide majority.

Brownlow's variety of federal nationalism was initially a pro-slavery version of Unionism, which was not uncommon in East Tennessee, and among the Border States. When Confederate forces stationed in Knoxville attempted to suppress Brownlow he continued venting his hatred for secession in his scathing editorials. His specialty was ad hominem attacks. He loved to denounce his enemies and spotlight their shortcomings as much as he touted his dedication to the United States.

This small book shares some of the arch-Unionist's writings that he had eventually published in the form of the 1862 book Sketches of the Rise, Progress, and Decline of Secession; with a Narrative of Personal Adventures Among the Rebels. The lengthy-titled work was more popularly known as "Parson Brownlow's Book." Hastily pulled together in New Jersey after being arrested, jailed, and sent through the lines to Union held Nashville, he took both published editorials and personal journal entries to give the reader a unique perspective of unabashed East Tennessee Unionism.

Editor Ash does a wonderful job of providing a helpful and contextual introduction and giving footnotes to a number of the perhaps more obscure references that Brownlow made in his original book. I've not read the original version, but as I understand it, it is somewhat repetitive, and Ash appears to have selected the choicest elements as presented in his edited offerings.

Despite one's personal thoughts about Brownlow and his sometimes questionable actions, particularly after the war, I recommend this book to better understand those individuals and their communities, who rejected secession and maintained their allegiance to the United States in such a fiery trial.

Thursday, August 30, 2018

Searching for Charles Plummer Tidd

Taking a few days of annual leave from work I was able to spend a good deal of that time enjoying the beautiful ocean scenery at Atlantic Beach, North Carolina. Before setting out on the trip, and as I often do, I searched for some intriguing historic sites to potentially visit either on the way down or the way back.

Remembering that my route led through New Bern, I recalled that I had once read that one of John Brown's raiders was buried there. Doing a quick internet search I located on findagrave.com that Charles Plummer Tidd was buried there in Section 8, Plot 40. That seemed easy enough. I had been to enough national military cemeteries to know that finding the grave with that information in hand should be no problem. Well . . . .

First, though, a little bit of background information on Tidd: Born in Palermo, Maine in 1834, Tidd migrated to Kansas in a party of free state settlers with Dr. Calvin Cutter of Worchester, Massachusetts in 1856. While in Kansas Tidd met John Brown and they became fast friends. Tidd's active abolitionism was evidenced in his participation in a raid Brown conducted into Missouri, which eventually brought Canadian freedom to 11 enslaved individuals.

Apparently eager to involve himself in Brown's grand plan to raid Virginia, but apparently unaware of the ultimate target of Harpers Ferry, Tidd traveled with Brown through various northern states and Canada in preparation for the adventure to the Old Dominion. He joined with Brown's tiny army gathering at the Kennedy farmhouse in rural southern Maryland in the summer of 1859.

Once Tidd found out that Harpers Ferry was Brown's intended target, he flew into a rage and left the Kennedy farmhouse to visit his friend and co-raider John E. Cook for a week in Harpers Ferry. Brown had previously sent Cook ahead to covertly study to town. Eventually, Tidd returned and like the others, who doubted the Brown's plan recommitted themselves.

Shortly before the raid, and knowing the likelihood of being killed in the raid, Tidd wrote to his family: "This is perhaps the last letter you will ever receive from your son. The next time you hear from me, will probably be through the public prints, If we succeed the world will call us heroes; if we fail, we shall hang between the Heavens and the earth." Although committed to doing his part, on the other hand, Tidd seemed to have a sort of nonchalance about the raid. He wrote often to female friends across the North telling of the preparations for the mission, feeling he could trust them to keep it secret

The plan for the raid as far as it concerned Tidd what that he and Cook were to go ahead and cut telegraph wires in advance of Brown and eighteen other raiders. Three men were to stay in Maryland at the Kennedy farm: Owen Brown, Barclay Coppoc, and Francis Jackson Merriam, all three being the least psychically fit.

Tidd, Cook, Aaron Stevens, and African American raiders, Lewis Leary, Sheilds Green, and Osborne Perry Anderson were then detailed to go capture Lewis Washington, George Washington's great grand nephew, who lived nearby. They did so bring with them a Washington pistol and sword. They then stopped at John Allstadt's Ordinary, taking more hostages and liberating six slaves.

Early on the morning of the 17th, Tidd was detailed by Brown to go back into Maryland capture another slaveholder named Byrne and then take Byrne's slaves and go to the Kennedy farmhouse and move forward firearms to an old log schoolhouse closer to Harpers Ferry. He did so, leaving the slaves guarding the weapons, Tidd returned to the Kennedy farmhouse. There Tidd learned from Cook that the situation in Harpers Ferry was desperate.

Tidd, Cook, Owen Brown, Barclay Coppoc and Merriam decided to make their escape from the Kennedy farm rather than be captured or killed attempting to rescue the other raiders, so they made their way north through Maryland into southern Pennsylvania. Cook was captured near Chambersburg searching for food. The frail Merriam disguised himself and took the train north, while the others, including Tidd, continued the trek by foot. By November 24 they reached Centre County, Pennsylvania, and each went separate ways. Tidd went to Chatham, Canada.

I was unable to learn how long Tidd remained in Canada, but he eventually found his way back to Massachusetts. He enlisted in Company K of the 21st Massachusetts on July 19, 1861 in Worchester, just west of Boston. Tidd, in order to maintain his true identity and thus association with Brown's raid, dropped his last name and enlisted as Charles Plummer.

Tidd received promotion to 1st Sergeant of Company K on November 1 1861. The following winter, the 21st Massachusetts received orders to participate in the coastal operations at Roanoke Island, North Carolina, being conducted by Gen. Ambrose Burnside. They embarked on the ship Northerner, and soon after landing Tidd died of enteritis, an inflammation of the bowels on February 7, 1862. The 21st Massachusetts regimental history states that Dr. Cutter, the man Tidd followed to Kansas and later became the 21st's surgeon, attended to Tidd and that the good doctor's daughter and regimental nurse, Miss Carrie E. Cutter, closed Tidd's eyes in death.

The regimental history of the 21st Massachusetts also says that Miss Cutter died on March 24 of spotted fever: "Her body was carried to Roanoke Island and buried by the side of her admired friend, Seargent Charles Plummer Tidd, the heroic companion of John Brown, whose eyes she closed so sadly during the battle of Roanoke Island." (page 83).

New Bern National Cemetery was established on February 1, 1867, and contains the Union dead reinterred from the coastal war-time battlefield cemeteries like New Bern, Morehead City, and Beaufort, as well as those who died of disease in the area hospitals.

I arrived at the New Bern National Cemetery on a sunny, hot, and humid day excited to find Tidd's grave. Near the entrance is an enclosed box containing a list in alphabetical order of the known interments and their plot numbers. I thought it would be best to consult the list. First checking for Tidd, and then Plummer, I only came up with a Charles E. Plummer, who had served in an artillery unit and had died in 1864, not 1862. I began to feel a little doubtful.

However, still determined, I went ahead a used the information I found online and located section 8, but there was not a plot number 40. I then went through all of section 8's graves and did not find a Tidd or Plummer. I finally went to the far back of the cemetery and found plot 40, but it, too, was not a Tidd or Plummer.

The cemetery office appeared to be closed, so I was unable to find additional help. But, despite my disappointment in not locating Tidd's grave, I was buoyed somewhat by several beautiful monuments to the Union dead in the cemetery. One, pictured above, is dedicated to the Massachusetts troops buried there, of which there appeared to be hundreds.

Monday, August 27, 2018

Coming into the Lines

Last week I shared Civil War artist Edwin Forbes's "The Sanctuary." Today I thought I share another telling image that Forbes created, "Coming into the Lines."

His book, Thirty Years After: An Artist's Memoir of the Civil War is on overlooked resource. It includes his recollections on events he witnessed and images that he sketched. Originally published in 1890, it written by a man of his times. Here is his description of a group of African American refugees coming into Union lines. The above image illustrates the description.

"I saw a quaint family come into camp one summer day in '63 at Culpeper Court House. I was at a picket post southeast of the town, when I noticed a vehicle approaching that was a mystery. I knew that no single baggage-wagon would come from that direction, and on waiting for a nearer approach found it to be a party of refugees. The team was composed of an old white horse, a white ox, and a mule. The horse was led by a man, who carried an old banjo under his arm, and a boy mounted on the mule was driver.

The wagon was an old-timer, and had evidently seen long service on the plantation. It was a so-called "schooner" in style, and its shape reminded on of a sailing vessel. It was bereft of the usual canvas cover, but three of the frame-hoops made to support it still remained, arched over the body. The occupants were an old "mammy" and her better half - his gray locks surmounted by an old white hat, - a young woman and two children. A bonnet was suspended from one of the hoops for safe keeping. This article of feminine apparel created much amusement among the soldiers, and from the scornful way in which the young woman resented their remarks I am sure it must have belonged to her. The whole turnout made a great deal of fun for the soldiers, and witticisms were launched forth all along the line. I laughed wit the rest and wondered, if the odd picture could be transported to Broadway, New York, what kind of a sensation it would produce."

When so-called contraband came into Union lines, as mentioned above, they were not always well received. Most often the reverse was true. However, their determination to leave the world of the enslaved and enter the world of free labor, despite all of the risks and sacrifices that entailed was worth all the verbal abuse and potential dangers of sickness and want. It was their first step in a long, long, long, road toward true liberty, citizenship, and equality.

Forbes concluded this memory by viewing the progress former slaves had made in the quarter century since the Civil War; again in his 1890 way: "And how these simple people have adapted themselves to circumstances and settled down to the struggle for existence as freedmen! They have kept good their promises, and the progress they have made is a full recompense for the sacrifice made for them and the protection they received. Their industrial value, not only as agricultural laborers, as in times "befo' the wah," but in diverse mechanical callings, is gradually winning for them the appreciation of their white neighbors, and they are steadily advancing towards a proper recognition of their worth."

Saturday, August 25, 2018

Just Finished Reading - A Nation Under Our Feet

A Nation Under Our Feet: Black Political Struggles in the Rural South from Slavery to the Great Migration is an important book that follows the treacherous paths that rural Southern African Americans have blazed politically from slavery to the 1920s. Hahn crafts this work through his meticulous research and expert analysis.

Throughout the book Hahn shows the ever important work of grass-roots agency networks in the black community, and the solidarity that developed that has highlighted black political efforts in the South. These often dangerous efforts to have a political say in their lives and to effect change often met massive violent white resistance throughout the period the author examines.

Hahn points out that even in slavery, when blacks had no official political representation or the ability to petition, their actions (insurrections, running away, etc.) influenced governmental policies that ultimately led to the end of the peculiar institution. The chapters on Reconstruction and Jim Crow likewise provide excellent insight into the organizing and communication networks in black communities that led to not only opportunities to participate actively in the democratic process, but also lead in official capacities on the local and state levels. These changes led to greater opportunities for rural blacks to obtain an education and achieve a level of economic independence previously believed to be impossible. The Union Leagues and Republican Clubs had tremendous appeal to rural blacks during the Reconstruction years due to their perseverance and results.

Also of great interest is Hahn's discussion on political black/white fusion efforts such as the Readjusters in Virginia and Greenbackers in Texas. When the Republican tide of Reconstruction subsided, and thus the reemergence of white supremacy in politics, in many areas emigration movements became a popular idea for regaining a sense of black political agency. Liberia, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Indiana all experienced at least some transplants from the former slave states in the last quarter of the 19th century.

Hahn's greatest accomplishment with this book though, in my opinion, is taking what could be a very convoluted topic, and through his skillful writing, makes it quite clear and understandable. This is truly a monumental book and certainly worthy of its Pulitzer Prize. I highly recommend it.

Friday, August 24, 2018

Then and Now - 1865 and 2018, Petersburg's Tabb and Union Streets

The above image of Petersburg's capture by Union forces on the morning of April 3, 1865, appeared in the April 22 issue of Harper's Weekly. The 2nd Michigan is shown raising the United States banner over the city's custom house. Some Union soldiers are marching west on Tabb Street, while others march on Sycamore Street in the distance.

The columned Tabb Street Presbyterian Church is clearly identified on the left edge. At that time it had a steeple. In the center background is the Petersburg Hustings Courthouse with a U.S. flag flying from the cupola.

Today, a steepleless Tabb Street Presbyterian and the old three-story Customs House, now Petersburg's City Hall, both still dominate the scene. However, taller new buildings have filled in the scene and obscure the old Courthouse.

Thursday, August 23, 2018

Wednesday, August 22, 2018

"The Sanctuary"

It is an indisputable fact that thousands of enslaved people flocked to Union army lines as they made incursions into the slave states. From the beginning of the conflict, although the abolition of slavery was not yet a stated war aim, African American men, women, and children believed that the dissonance caused by the conflict was their path to freedom.

Artist Edwin Forbes remembered from this wartime experience a family of so-called contrabands coming in to Union lines.

"Meager possessions were packed quickly when news came to a plantation that the Yankees were holding a near-by town, and although the country was picketed with Southern cavalry close up to the Union lines, the slave family stole from the old cabin at nightfall, and avoiding highways to escape capture, tramped through wood and thicket, and came weary and footsore, in sight of the Union lines at daybreak.

I saw one group that I never shall forget, it impressed me so deeply with what the Federal success meant to these dusky millions. The old mother dropped to her knees and with upraised hands cried 'Bress de Lord!' while the father, too much affected to speak, stood reverently with uncovered head, and the wondering bare-legged boy, with the faithful dog, waited patiently beside them, As the bugle notes of the reveille echoed across the fields, and the star-spangled banner waved out from the flag-staff on the breastworks in the bright morning sun, I murmured, 'A Sanctuary, truly!'"

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Sunday, August 19, 2018

A John Brown's Raid Site Visitorama

As I posted on Thursday evening, I had the great fortune of attending the National Park Service historians August tour to Cool Springs Battlefield, where I got to see John Brown's trial judge, Richard Parker's, second home "Retreat." Later that day we also visited Belle Meade Plantation, which is just south of Winchester where we learned about the significant archaeology work going on there. This work is helping them to better tell the story of the enslaved that lived there in their programming.

Staying the night in Winchester, I got up early on Friday morning to do some John Brown raid site seeing in adjacent Jefferson County, West Virginia, and over across the Potomac River in Maryland, too. I did not visit the sites in the order they are presented here. Rather, I've place them in roughly in chronological order as they occurred during the raid.

I stopped at the Kennedy farmhouse (shown above), which Brown rented under the name of Issac Smith, in the summer of 1859. The log and stone building is about five miles or so from Harper's Ferry along a winding section of road. The headquarters/home has recently been restored and a couple of Civil War Trails waysides stand in the yard interpreting the events that swirled there in 1859, and later during the Civil War.

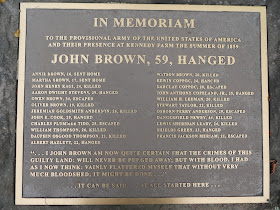

I visited the Kennedy Farm site about ten years ago. At that time a chain link fence kept visitors at a distance from the historic structure. But on this visit I had the opportunity to get an up close look at the home. On a large boulder between the house and the parking area by the road, the above memorial plaque lists the names, ages, and fates of Brown's small raiding force. The site is a National Historic Landmark and is available for tour by appointment. Interestingly, items left at the Kennedy Farm by the raiders were used as evidence in the trial in Charles Town after Brown and a number of his men were captured in Harper's Ferry and jailed at the county seat.

Between Harper's Ferry and Charles Town is Beallair, the period home of Lewis Washington, who was the great-grand nephew of George Washington. John Cook, one of Brown's raiders, had his made residence in the area to scout it out before the raid and determined that Washington would make a good hostage and his slaves would make recruits for the army the raiders were trying to build.

Lewis Washington was taken captive on the night of October 16 and moved to Harper's Ferry. John Cook and African American raider Osborne Perry Anderson were at the house, they took a sword that Frederick the Great had given George Washington and which had devolved to Lewis Washington.

Several dependency buildings, both attached (above) and detached (two below) are also on the property. I would guess that the building above was used for house slave quarters and the stone building below was likely the kitchen.

Another stone building sits just across the road. This may have served as other slave quarters or may have been a workshop of some type, as I do not remember seeing a chimney on the building. However, it may have been heated with a stove instead of fireplace/chimney.

All of the buildings are in good condition, and although housing development has encroached and certainly changed the landscape, it is good to know there is an effort to keep the original structures in place and in good repair.

After taking Washington and a handful of his slaves, Cook and Anderson moved on toward Harper's Ferry and stopped at Allstadt's Ordinary. At his home, tavern, and small inn along the turnpike the raiders took more hostages including John Allstadt, his teenage son John Thomas Allstadt, and seven of their slaves.

Several of the raiders and hostages ultimately ended up in the armory's fire engine house (shown above) in Harper's Ferry. The present site of the engine house is not where it originally stood. It has been moved at least four times since the 1859 events.

Near the original site of the fire engine house runs Hog Alley (shown above). It was here that free man of color and raider Dangerfield Newby was killed when hit with a projectile in the neck. Newby's body was first mutilated by townspeople and then left to be eaten by hogs. Thus the alley received its name.

Brown's trial was held at the Jefferson County courthouse (shown above). He was, of course, found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging.

Brown's last days were spent largely in the Jefferson County jail. Here, now the site of the town's post office, the chief raider received letters, visited with a both friends and enemies, and wrote to supporters of his abolitionist cause.

On December 2, 1859, Brown was taken to the city's southern outskirts where a gallows stood, constructed for the occasion. At shortly before noon, and before witnesses such as John Wilkes Booth and Thomas Jonathan Jackson, Brown was hanged. His hanging made him a martyr in abolitionist circles. And then the war came. It wouldn't be long before Union soldiers created the marching song known as "John Brown's Body."

If you travel to Jefferson County, West Virginia, be sure to stop by the Charles Town visitor's center and pick up a copy of their "John Brown's Trail" brochure, which give directions to all of the sites mentioned above.

Thursday, August 16, 2018

Judge Richard Parker's "Retreat"

Today I attended the August edition of the National Park Service historian's tour. The first place we visited was the Cool Springs Battlefield in Clarke County, near Berryville, Virginia. Fought on July 18, 1864, this battle occurred partly on the land owned by Judge Richard Parker (shown below). Those of you who are John Brown students likely recognize Parker's name from Brown's trial in Charlestown, Virginia (now West Virginia) in the fall of 1859. Parker presided over the trial, and after Brown's jury found the militant abolitionist guilty, Parker ultimately pronounced Brown to be executed by hanging on December 2.

Parker's 1,120 plantation, known as "Retreat," served as a second home for the judge. His primary residence was in Winchester, where he practiced law. Parker is listed in 1860 as the owner of nine slaves in Frederick County (Winchester). In that census Parker is shown as a 49 year old circuit court judge and has personal property worth $10,500 and real estate in valued at $7,500.

Bounding Parker's "Retreat" property is the beautiful Shenandoah River. Although Shenandoah University now owns 195 acres of the land that was once Judge Parker's, the circa 1799 home pictured at the top is privately owned and is used as a bed and breakfast resort. For decades the surrounding land was part of a golf course.

Originally a road ran beside the house down to the Shenandoah River. At that point there was a ford across the stream to a rather small island barely visible on the top right of the photograph above and then to the north bank of the river. The land on the north side of the river, where the majority of the July 18, 1864 fighting occurred is presently owned by the Holy Cross Abbey, an order of Trappist monks.

Shenandoah University and their McCormick Civil War Institute director, Jonathan Noyalas, has developed an informative nine stop walking tour of the south bank property they own. If you are in the area, be sure to stop in and take in the beautiful scenery and learn about this overlooked battle.

Tuesday, August 14, 2018

Zooming in on a Civil War Sutler's Store

Searching for images of sutlers on the Library of Congress website, I happened across the one above. Unfortunately, not much information is provided as to when and where during the war the image was made. Like most images, some intriguing details can be found when one uses photo manipulation tools to zoom in on its scenes.

In the center of the shot a walk up sales window appears to be made into the side of the sutler's structure. In the background a proprietor peers through the window while holding what looks to be a knife in his right hand while resting his head his left hand. I wonder if he is resting his right hand and knife on wheels of cheese or some type of round boxes? The soldier on the left is sporting a low-crown hat and has visible braces (suspenders).

There are several African American boys and men in the photograph. The boys probably served in a servant role doing camp chores for the officers. One of the soldiers (with some fancy braces!) has his left hand on one of the boy's head.

Two other boys relax on the far left of the photograph. The boy closest to the photographer is barefoot. Both appear to be wearing Union army forage caps. I wonder if these boys are orphans or if they ran away together. Were they brothers, or perhaps cousins?

The right-center group of soldiers offer a drinking scene. Often sutlers were prohibited from selling alcohol in army camps by officers, while others allowed it at certain times. Here a wooden barrel and a stoneware jug appear to be the vessels for the liquor.

Three young black men are in this scene. The one of the left looks to be wearing a Union issue fatigue blouse. The one in the center appears to be wearing a unique hat of some sort. The white soldier between the two black men on the right is wearing an unusual coat or wrap that has either a hood or a large collar. It appears he is also holding an umbrella.

I'm not sure what is happening in the above scene. It may be posed. An officer is standing with his right hand out as if he is lecturing the groups of drinking men. Behind him a man in a duster is either mocking the officer or may be playing an air trumpet. Ha!

The roof of the sutler's structure has a piece of canvas over the center. There doesn't appear to be writing on it that would indicate it being a sign. Rather, the roof probably leaked and the canvas served as an additional barrier against the elements.

The TIFF image can be down loaded here. Can you find any other interesting details?

Friday, August 10, 2018

Just Finished Reading - The Loyal Republic: Traitors, Slaves, and the Remaking of Citizenship in Civil War America

In The Loyal Republic: Traitors, Slaves, and the Remaking of Citizenship in Civil War America, author Erik Mathisen primarily uses the Mississippi Valley as his geographic focus. It is a good choice on his part due to all of the change this region experienced during the Civil War and Reconstruction. Although Mississippi was the second state to secede there were pockets where loyalty to the United States remained strong, and it was home to individuals who were unwilling to claim allegiance to the newly formed Confederacy. Among those that did side with secession, the author intriguingly also examines the seemingly cloudy world of whether one's greater loyalty was to the state of Mississippi or the Confederate nation. On the surface this may seem one in the same, but when "push comes to shove" issues arose it made for tough decision making.

This era brought opportunities for African Americans to demonstrate their loyalty to the United States by fleeing their owners and entering Union lines to either provide needed labor or enlist as soldiers when finally allowed to do so in 1863. Blacks would use their loyalty as a leverage point during the initial Reconstruction years that Confederate whites could not. The formerly enslaved, especially those who had fought in USCT regiments, demanded their citizenship be recognized in the forms of Constitutional amendments (14th & 15th) and bred resentment by former Confederates who basically lost their citizenship rights for a time.

The Loyal Republic is a thought provoking work that makes one reexamine preconceptions of loyalty and citizenship and how we came to our current understanding of those terms. I recommend it.

Tuesday, August 7, 2018

The Burnside - Fulkerson Kerfuffle: June 17, 1864

Monday evening while browsing through issues of the Bristol News (VA & TN) from 1868, I came upon the advertisement above for attorneys York and Fulkerson. The name Fulkerson certainly rang a bell for me. When I lived in Tennessee and reenacted, I participated with the 19th Tennessee Infantry. The original 19th Tennessee, a Confederate regiment raised in a heavily Unionist East Tennessee, fought in most of the western theater battles. Abram Fulkerson first served as captain of Company K and then as major in the 19th. Later he received a promotion to lieutenant colonel and the colonel of the 63rd Tennessee.

Fulkerson's family came from Lee County in far southwest Virginia, near the Cumberland Gap. The Fulkerson's had a long line of men in military service. Abram's grandfather fought in the the Revolutionary War and his father, Abram Sr., fought in the War of 1812. Abram was educated at the Virginia Military Institute, where he learned from Thomas Jonathan Jackson. When the Civil war broke out Abram was teaching in Hawkins County, Tennessee. He joined with other Southern-minded neighbors to form Company K of the 19th Tennessee. Fulkerson's brother, Samuel Vance Fulkerson, an attorney in Washington County, Virginia (Abingdon), who had fought in the Mexican-American War, joined in the 37th Virginia. Samuel was killed fighting in the Battle of Ganines' Mill on June 27, 1862.

After Abram Fulkerson transferred to the 63rd Tennessee, the regiment was relocated to Virginia and fought in Bushrod Rust Johnson's Brigade. Johnson's Brigade was assigned to Gen. Beauregard's forces on the Bermuda Hundred, but were called to Petersburg when Gen. Grant's first offensive threatened the city. During the initial fighting at Petersburg, Johnson's Brigade received heavy assaults from the attacking IX Corps Union forces east of the Cockade City. On June 17, Fulkerson's position was overrun and he was captured.

Fulkerson recalled the incident and his subsequent interrogation by IX Corps commander Gen. Ambrose Burnside (pictured above) in an 1894 piece he wrote for the Southern Historical Society.

"About daylight, on the morning of the 17th, the troops in our front, having been largely reinforced during the night, made a charge in three lines on our position, overlapping us on the right, and carrying our works by storm. A large portion of Johnson's Brigade was captured, including myself and about half of my regiment.

The prisoners, in charge of an officer and a detail of men, were quickly marched through the Federal lines to General Burnside's headquarters, located in a field about half a mile to the rear. The General had dismounted, and was seated on a camp-stool, and was surrounded by a line of negro guards.

The prisoners were halted at the line of guards, and the officer in charge announced to the General that they has captured the colonel of a regiment, many officers and men, three flags, and several pieces of artillery. Rising from his seat, General Burnside approached us, and, addressing me, enquired what regiment I commanded, and being informed that it was a Tennessee regiment, he asked from what part of the State.

From East Tennessee, I replied. With an expression of astonishment, General Burnside said: 'It is very strange that you should be fighting us when three-fourths of the people of East Tennessee are on our side.' Feeling the rebuke unjust and unbecoming and officer of his rank and position, I replied, with as much spirit as I dared manifest, 'Well General, we have the satisfaction of knowing that if three-fourths of our people are on your side, that the respectable people are on our side.' At this the General flew into a rage of passion, and railed at me.

'You are a liar, you are a liar, sir, and you know it.' I replied, 'General, I am a prisoner, and you have the power to abuse me as you please, but as to respectability that is a matter of opinion. We regard no man respectable who deserts his country and takes up arms against his own people.' To this General Burnside replied, 'I have been in East Tennessee, I was at Knoxville, I know these people, and when you say that such men as Andrew Johnson, Brownlow, Baxter, Temple, Netherland, and others, are not respectable, you lie, sir, and you will have to answer for it.' At this point I expected he would order me shot by his negro guards, but he continued, 'not to any human power, but to a higher power.' With a feeling of relief I answered, 'O, General, I am ready to take that responsibility.'

'Take him on, take him on,' the General shouted to our guards, and thence we were marched some two or three miles towards City Point, to the headquarters of General [Marsena] Patrick, the Provost-Marshall General of Grant's army, where we were guarded during the day in a field, without shelter, and under a burning sun. In other respects we were treated with consideration due prisoners of war by General Patrick, whom we found to be a gentleman."

Sent to Charleston, South Carolina, Fulkerson became part of the Immortal 600 group of prisoners. Eventually he was transferred to Fort Delaware, where he was finally released in July 1865. After the war Fulkerson went into law and then politics, serving in the Virginia legislature and then the U.S. House of Representatives. He, along with William Mahone, was one of the founding members of the controversial biracial Readjuster Party in Virginia. Fulkerson died in Bristol in 1902 and was buried in East Hill Cemetery.

Saturday, August 4, 2018

Recent Acquisitions to My Library

The most recent issue of the Civil War Monitor magazine listed several historians' favorite books about Gettysburg. One that appears on several lists was The Color of Courage: Gettysburg's Forgotten History, Immigrants, Women, and African Americans in the Civil War Defining Battle by Margaret S. Creighton. I have seen this work at different book stores and at historic sites, but with a number of Gettysburg books already on my shelves, I did not have an urgency to add another. However, after attending the Gettysburg College Civil War Institute back in June, I came across a few of the town's intriguing social history stories while walking around and reading a number of wayside panels and roadside markers. Interested in learning more, this book seemed like an excellent opportunity to do so.

Braxton Bragg: The Most Hated Man of the Confederacy by Earl Hess is a book that I've had on my wish list since it was published a couple of years ago. Bragg's previous two volume biography is often the butt of jokes in Civil War circles. Having a different author for each volume lends itself to the thought that a historian can only stand so much of Bragg before calling it quits. Apparently with this new biography Hess provides a balanced look at Bragg's service and leadership, taking into account his personal life and its influence on this thoughts and actions. Curious to learn about Hess's sources and his interpretation, I'm looking forward to viewing this Army of Tennessee historical pariah from a new perspective.

The John Brown shelf in my library just grew by another volume with my purchase of Five for Freedom: The African American Soldiers in John Brown's Army by Eugene L. Meyer. Recent individual biographies on John Brown's raiders John Cook and John Anthony Copeland, both by Steven Lubet, are bringing the stories of Brown's men more into focus. The five African American men covered in this work all have fascinating life stories and I'm looking forward to learning more about them. Osborne Anderson, John Anthony Copeland, Dangerfield Newby, Shields Green, and Lewis Leary all had lots to lose with their participation in the Harpers Ferry raid, but made the attempt anyway. The fact that, of the five, only Osborne Anderson escaped, shows their sacrifice in their effort to end slavery.

I read Tiya Miles's book The House on Diamond Hill, about Cherokee Joseph Vann's slaveholding plantation in Georgia a few years ago and was fascinated by this racially complex story. Marginalized Native Americans owning enslaved African Americans is a complicated story that she helped me sort out. In Ties that Bind: The Story of an Afro-Cherokee Family in Slavery and Freedom, Miles seeks to teach us more about the the black and red dynamic of slaveholding and family.

Although I moved from Kentucky just over three years ago, my interest in that state's history endures. Home Rule: Households, Manhood, and National Expansion on the Eighteenth Century Kentucky Frontier by Honor Sachs looks to provide further evidence to rather recent interpretations about the influence of Kentucky's frontier experience as a model for other states in westward expansion. Often at the expense of women, slaves, the poor and less established, a white masculine patriarchal dominance established a sense of order on the turbulent and sometimes dangerous frontier.

I've been seeking to learn about the experiences of white officers who led black troops during the Civil War for quite some time. Thank God My Regiment an African One: The Civil War Diary of Colonel Nathan W. Daniels, edited by C. P. Weaver, examines the experiences of a commander of the 2nd Louisiana Native Guards, a regiment made up of free men of color from New Orleans and the Pelican State. I'm interested to see how Daniels's account is similar and different from those of more well known commanders like Thomas Wentworth Higginson's book and Robert Gould Shaw's collection of letters.

Thursday, August 2, 2018

Just Finished Reading - The Color of Christ: The Son of God and the Saga of Race in America

By examining an array of sources, including material culture, and from the perspectives of different groups of African Americans, Native Americans, and whites, it is clear that over time that the image of Christ that became most envisioned was that of a white Jesus. Obviously this required ignoring Christ's Middle Eastern Jewish heritage.

Puritans and some other colonial Americans often attempted to exclude and even destroyed pictures of Jesus from their worship, preferring to symbolize Christ with light rather than with a flesh and blood image. Early American whites developed a white Christ to fit their world view and attempted to share their image with the enslaved of African descent and the "sons of the forest," Native Americans, with a measure of success. With emancipation and westward expansion, conflicting views of Christ's image came forward. Native American were confused that whites idolized Jesus with long hair, yet required Indians to cut theirs to be "civilized." The Christ of many African Americans, who was a loving and forgiving figure became a vengeful and hateful figure when used by white supremacists like the KKK. The authors explain that the 1941 image "Head of Christ" by Walter Sallman is one that has dominated American's imagination in the 20th and 21st century. The influence of this particular image is enduring and became almost ubiquitous in protestant churches and in secular circles as well.

During the evolution of the Civil Rights Movement and with the rise of liberation theology, for many African Americans Jesus transformed from white to black and was depicted as such as a way of relating to the struggles endured during slavery, Reconstruction, and Jim Crow era America. The authors brings the story on into the present and explain how Jesus has been viewed in the digital age and in popular culture.

I appreciated that the authors included photographs of some of the imagery they examine. And by covering this topic over the span of centuries, it helps us see more clearly this fascinating change over time. I recommend it highly.