My musings on American, African American, Southern, Civil War, Reconstruction, and Public History topics and books.

Sunday, June 25, 2017

A Visit to Eppington Plantation

As a way of thanking our wonderful volunteers at work, I arranged a tour of Eppington Plantation in southwest Chesterfield County last Thursday. We received an educational and informative tour through this almost 250 year old preservation treasure.

Now owned by the Eppington Foundation, and managed by Chesterfield County, this historic home was built by Francis Eppes VI on land he inherited from his father Richard Eppes. Construction began in 1768 on the Georgian center section of the home, and apparently Eppes moved in in 1773. The wings were added around 1790. Most of the materials were taken from the surrounding forests and fields and constructed through skilled enslaved laborers. One exception is the glass, which apparently came from Europe. The heart-of-pine floor boards stretch for yards and yard and makes one wonder what size of trees they came from.

Inside the house the skilled work necessary to build an eighteenth century home is evidenced through the woodwork, plaster work, and other visible methods of construction. The house is presently undergoing an extended preservation effort. Due to the costs of a quality restoration, areas of most need are receiving top priority, while others wait. In addition to its preservation there is a plan in place to recreate several of the outbuildings such as the summer kitchen and school building. The house stood on thousands of acres. The land immediately around the home featured landscaped and terraced gardens and orchards. The Appomattox River flowed a short distance away and was at the time visible through the cleared woodlands.

Francis Eppes VI was the brother-in-law of Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson's wife, Martha Wayles Skelton was the sister of Elizabeth Wayles, who married Eppes in 1771. Eppes and Jefferson developed a close relationship, probably due as much to their common interests, as to their marriage to sisters. Both men were fascinated with plants and agriculture. Both men managed large plantations and hundreds of enslaved people on thousands of acres of land. Jefferson, Eppes, and John Wayles, their father-in-law, also had common ground through he Hemmngs family. Wayles owned Betty Hemings and fathered Betty's daughter Sally. Betty's daughters, Sally and Critta, both served Eppes at Eppington, and after Jefferson's daughter Lucy died at Eppington, Sally was sent with Jefferson's other daughter, Maria, to assist Jefferson in France. It is readily believed that later, Sally fathered children by Jefferson at this Monticello.

Eppington is only open to the public on limited occasions or special arrangement, so we felt particularly fortunate to have the opportunity to learn about his historical treasure and its place in Virginia's history. If you are wishing to visit Eppington, they will be having a special event in early October, so please consider taking advantage of the opportunity. I promise, you will be impressed.

Wednesday, June 7, 2017

A Visit to Deep Bottom and New Market Heights

I took advantage of some unseasonably cool June weather early this morning to take drive up to the New Market Heights Battlefield and the Deep Bottom crossing point on the James River. I had never visited Deep Bottom, so it was a treat to see the famous location that appeared in many period photographs and often served as the Union army's route of transfer between the Petersburg and Richmond fronts during the summer and fall of 1864.

The Deep Bottom area figured prominently into Gen. Grant's offensive plans to keep Lee's limited manpower resources tied down and less able to support one another on the two fronts. The first action there was in association with Grant's Third Offensive at the end of July 1864. On the 28th, Grant had Hancock's II Corps move across the bridge from Petersburg and sent Sheridan's cavalry on a move toward the Confederate defenses from Deep Bottom, but they were turned back by forces in Lee's Second Corps under Gen. Joseph Kershaw. This setback combined with the failure of the Battle of the Crater at Petersburg did not dissuade Grant from his strategic campaign goal.

The second movement involving a crossing at Deep Bottom's pontoon bridge occurred in mid-August in conjunction with the movement at Petersburg toward the Weldon Railroad in what was Grant's Fourth Offensive. Again, Hancock's II Corps was involved. However, this time Gen. Birney's X Corps movement on the left flank of Lee's line drew a fierce counterattack at Fussel's Mill that resulted in a Federal retreat with the fighting occurring over much of the same ground as that a half a month before. Although this movement did not result in a substantial gain, it did keep some of Lee's forces occupied north of the James River while Grant snapped the Weldon Railroad at Globe Tavern outside of Petersburg.

Finally, in late September, Gen. Butler's Army of the James tested Lee's Richmond defenses at Chaffin's Farm. The Army of the James, which consisted of the X Corps and XVIII Corps, crossed the Deep Bottom bridge and hit the Confederate earthwork line along the New Market Road. Fierce resistance saw savage fighting between Gen. Gregg's Texas Brigade and African American soldiers of Birney's X Corps. Fourteen black soldiers earned the Medal of Honor for their fighting spirit at New Market Heights, where they captured the rebel works. The XVIII Corps also experienced initial success farther to the west capturing sparsely held Fort Harrison. Stiffer resistance was encountered at Fort Gilmer, just to the north of Fort Harrison, where many of the Texans ended up facing some of the same black troops they had fought earlier in the day at New Market Heights. Gen. Lee attempted a counterattack the following day in attempt to regain Fort Harrison, but was unsuccessful and things settled back into stalemate mode again.

It is a shame that the New Market Heights battlefield is not more accessible and better interpreted than it is. Only a Civil War Trails wayside sign and the above highway marker are posted to inform the public about this significant action where African American soldiers proved they could fight as well as any white troops.

It would only be just for some type of monument to be erected at the little park just east of the I-295 and New Market Road intersection to honor those soldiers that fought so gallantly at New Market Heights. Hopefully, some day that tribute will come to fruition.

Deep Bottom historic photograph courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Photographs of present-day Deep Bottom and the New Market Heights marker by author June 7, 2017.

Saturday, June 3, 2017

What was Jones Farm?

When listing the various battles that occurred during the Petersburg Campaign, they often include "so-an-so's farm" as a mark of identity and location. There's the Battle of Baylor's Farm, the Battle of Peebles Farm, the Battle of Lewis Farm, and the Battle of Jones Farm. The military fighting that occurred on the fields and woodlots that covered these acres have received much more coverage than their original interned purpose of agricultural enterprise.

However, by doing a little basic research, one can gather quite a bit of information about the owners and the operation of these farms (or more accurately in many instances, plantations). Such was the case of Robert H. Jones's place, just southwest of Petersburg. The picture above shows part of land on which the Jones Farm once occupied.

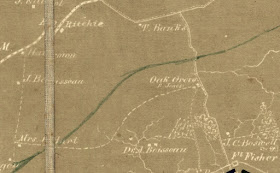

Robert H. Jones was a tobacco inspector and planter. His home, "Oak Grove" was located along the west side of Church Road, but apparently the plantation encompassed both sides of road. In 1860, the fifty year old Jones had land holdings valued at $57,800, which consisted of 700 improved acres and 320 unimproved acres. He owned another $5000 in farming implements.

Jones's Oak Grove bordered the neighboring plantations of Mrs. Thomas Banks, Joseph G. Boisseau (brother in law), Albert W. Boisseau (brother-in-law), and J.C. Boswell. In the household along with Robert was his second wife, Ann E. Boisseau Jones, who Robert married around 1850. Mary was the sister of Robert's first wife, Martha Eliza T. Boisseau, who wed Jones in 1834, but died in 1840. Ann and Martha's mother, Athaliah Boisseau, also lived with the Jones couple, as well as nephew Adrian (twelve), the son of Robert's brother-in-law William E. Boisseau, who along with his wife, Julia, had died in Alabama in 1854. In addition, forty-five year old Thomas Ritcherson is included in the Jones home. Jones's personal property is listed at $57,000 and real estate at $10,000.

As one might imagine, Jones worked a large enslaved labor force on his one thousand plus acre plantation. The 1860 census lists him owning seventy-four men, women, and children, who lived in seventeen slave dwellings.

The 1860 agricultural census is a significant key to better understanding Oak Grove plantation at this time. As far as animals, enumerated were four horses, eighteen asses and mules, eight milk cows, and ten other cattle. That may sound like quite a small sum to help feed a plantation family and their enslaved workforce until one reads the following line of two hundred swine, which provided the bulk of the meat consumed on Southern plantations. All of Jones's livestock was valued at $5330.00.

Also listed were the crops grown on the plantation. They were: three hundred bushels of wheat, ten bushels of rye, 5500 bushels of Indian corn, three hundred bushels of oats. Also listed are 3000 pounds of tobacco, which seems like a very small amount to keep seventy-four slaves engaged. Perhaps Jones leased out some of his surplus slaves, but that is merely speculation on my part.

The Jones Farm endured fighting not once, but twice. Its first experience was during the Peebles Farm fighting, September 20-October 2, 1864. However, it was on March 25, 1865, that the Jones Farm endured it most significant combat, with the family home being among the engagement's causalities. The house was set ablaze by soldiers in the Union VI Corps when it was utilized by Confederate sharpshooters. The March 25 engagement will be the subject of a future post.

Present-day photograph of Jones Farm by the author on May 20, 2017.

Period map of Jones Farm location courtesy of the Library of Congress.