After the severe fighting at Spotsylvania and more at North Anna, things were only about to get worse for the men that followed Grant and Lee. The Battle of Cold Harbor was only days away.

One of those men was Capt. Andrew J. McBride of the 10th Georgia Infantry. McBride's regiment was part of Gen. Goode Bryan's Brigade in Gen. Joseph Kershaw's Division (pictured) of Longstreet's Corps.

At the time of his writing McBride was about 28 years old and before the war had been an attorney. He had received a minor wound during the fighting in the Wilderness and would be injured severely enough at Cold Harbor to sit out the rest of the war.

150 years ago today, McBride wrote:

"Battle Field

May 29th 1864

The great battle is not yet over, there is only a lull - the first for twenty five days, the sullen roar of artillery even now reminds us that the last act of the bloody tragedy is yet to be enacted. - we all feel that Palida Moss is only temporarily satiated and even now hovers over the fair fields and blooming vales of Virginia ready to begin a carnival more cruel and more horrible than any he has yet held on the "dark and bloody ground" of the Old Dominion. - Aye we all feel, that yet another hecatomb of human bodies, slaughtered at the bidding of Abraham Lincoln, must rise to satiate the bloody Molock of the North. Alas! yes almost before the shriek of his wounded who perished in the flames of the burning wood in the Wilderness and at Spotsylvania have died upon our ears, almost before their blood dried upon the earth, the is ready with an unparalleled cruelty to offer new victims - Oh what strange dreams must fill his brain in the deep "silent watches of the night?" or if perchance in the "visions of the night" the Ghosts of his murdered victims (whose charred and blackened bodies now lie scattered by the thousands through the Wilderness and upon the heights of Spotsylvania) should pass in review his dream would indeed be more terrible than the reality witnessed by Richard the third - There are may incidents of a thrilling interest which I would like to relate, but cannot now. Grant after three desperate efforts, on as many different roads had been forced to his Gunboats on the Pamunky and York rivers, he is not at a position which he could have reached without the loss of a single man, but what a fearful price he has paid for it? his loss cannot have been less than fifty thousand while ours will not greatly exceed fifteen thousand - the great difference can be quickly and satisfactorily accounted for when it is remembered that we have fought most of the time, behind breastworks - but enough of these battles you will see better accounts of them in the papers. . . . I have been in command of the regt since the first day of the fight and have but little time to write if I can I will write to you before going into battle but I can hardly tell when that will be though it may be in a few hours."

If McBride thought Grant's previous attacks were "desperate," one can only image what he thought about the Union charges at Cold Harbor on June 1 and 3.

My musings on American, African American, Southern, Civil War, Reconstruction, and Public History topics and books.

Thursday, May 29, 2014

Tuesday, May 27, 2014

150 Years Ago Today - Pickett's Mill

To the east of the fighting at New Hope Church was the Confederate right flank. After being thwarted on May 25, Sherman sent Gen. O. O. Howard to go around the rebel right flank and force Johnston out of his defensive line. When Howard made his move on May 27, he ran into the hard-fighting division of Gen. Patrick Cleburne (pictured). Fighting late in day, the battle continued after dark with a night charge by Cleburne's Confederates.

Among the men in Cleburne's command was Captain Samuel Foster of the 24th Texas Cavalry (dismounted). Foster wrote of the action at Pickett's Mill:

". . .We find some Ark.[ansas] troops on the end of our line, and we form on to their right making our line that much longer and it also puts us just about where the scouts said the Yanks were going to try to flank our Army. Our position is in a heavy timbered section with chinquapin bushes as an undergrowth. From the end of the army, where the breastworks stop we followed a small trail or mill path as soon as our Brigade got its whole length in this place and the command is to halt! and at the same instant the cavalry skirmishers came running back to our lines, saying that we had better get away from there, for they were coming by the thousand. . . .

As soon as the skirmish line was put in position our men commenced firing at the enemy skirmishers who were not more than forty to fifty yards from us. One of my men Joe Harrison who never could stop on a line of that kind without seeing the Yanks ran forward through the brush, but came back as fast as he went, saying that they fired a broadside on him, but didn't hit him - He took his place on the skirmish line behind an Oak tree about 14 inches in diameter - The enemy kept advancing through the bushes from tree to tree until they were (some of them) in 30 or 40 feet of our line - nor would they give back. I had three as good men as ever fired a gun killed on this skirmish line - W J Maddox, T L Doran & T F Nolan. The two first named were shot thru the neck and killed instantly, the last one shot in the bowels and died in about 15 hours later. When the sun was about an hour high in the evening we were ordered back to the line of battle. And it seems that the enemys line of battle was advancing when the order came for the skirmishers to fall back.

The frolick opened in fine style as soon as we got back into our places - in stead of the two skirmish lines - the two lines of battle open to their fullest extent. No artillery in this fight - nothing but small arms.

Our men have no protection, but they are lying flat on the ground, and shooting as fast as they can. This continues until dark when it gradually stops, until it is very dark, when every thing is very still, so still that they chirp of a cricket could be heard 100 feet away - all hands lying perfectly still, and the enemy not more than 40 feet in front of us."

After the night charge which netted some Yankee prisoners, and Foster gained some "crackers bacon & coffee) Sherman moved back west. Foster commented on the terrible sights he witnessed the following morning:

"About sun up this morning we were relieved and ordered back to the Brigade - and we have to pass over the dead Yanks of the battle field of yesterday; and here I beheld that which I cannot describe; and which I hope never to see again, dead men meet the eye in every direction, and in one place I stoped and counted 50 dead men in a circle of 50 ft. of me. Men lying in all sorts of shapes and . . . just as they had fallen, and it seems like they have nearly all been shot in the head, and a great number of them have their skulls bursted open and their brains running out, quite a number that way. I have seen many dead men, and seen them wounded and crippled in various ways, have seen their limbs cut off, but I never saw anything before that made me sick, like looking at the brains of these men did. I do believe that if a soldier could be made to faint, that I would have fainted if I had not passed on and got out of that place as soon as I did - We learn thru Col. Wilkes that we killed 703 dead on the ground, and captured near 350 prisoners."

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Among the men in Cleburne's command was Captain Samuel Foster of the 24th Texas Cavalry (dismounted). Foster wrote of the action at Pickett's Mill:

". . .We find some Ark.[ansas] troops on the end of our line, and we form on to their right making our line that much longer and it also puts us just about where the scouts said the Yanks were going to try to flank our Army. Our position is in a heavy timbered section with chinquapin bushes as an undergrowth. From the end of the army, where the breastworks stop we followed a small trail or mill path as soon as our Brigade got its whole length in this place and the command is to halt! and at the same instant the cavalry skirmishers came running back to our lines, saying that we had better get away from there, for they were coming by the thousand. . . .

As soon as the skirmish line was put in position our men commenced firing at the enemy skirmishers who were not more than forty to fifty yards from us. One of my men Joe Harrison who never could stop on a line of that kind without seeing the Yanks ran forward through the brush, but came back as fast as he went, saying that they fired a broadside on him, but didn't hit him - He took his place on the skirmish line behind an Oak tree about 14 inches in diameter - The enemy kept advancing through the bushes from tree to tree until they were (some of them) in 30 or 40 feet of our line - nor would they give back. I had three as good men as ever fired a gun killed on this skirmish line - W J Maddox, T L Doran & T F Nolan. The two first named were shot thru the neck and killed instantly, the last one shot in the bowels and died in about 15 hours later. When the sun was about an hour high in the evening we were ordered back to the line of battle. And it seems that the enemys line of battle was advancing when the order came for the skirmishers to fall back.

The frolick opened in fine style as soon as we got back into our places - in stead of the two skirmish lines - the two lines of battle open to their fullest extent. No artillery in this fight - nothing but small arms.

Our men have no protection, but they are lying flat on the ground, and shooting as fast as they can. This continues until dark when it gradually stops, until it is very dark, when every thing is very still, so still that they chirp of a cricket could be heard 100 feet away - all hands lying perfectly still, and the enemy not more than 40 feet in front of us."

After the night charge which netted some Yankee prisoners, and Foster gained some "crackers bacon & coffee) Sherman moved back west. Foster commented on the terrible sights he witnessed the following morning:

"About sun up this morning we were relieved and ordered back to the Brigade - and we have to pass over the dead Yanks of the battle field of yesterday; and here I beheld that which I cannot describe; and which I hope never to see again, dead men meet the eye in every direction, and in one place I stoped and counted 50 dead men in a circle of 50 ft. of me. Men lying in all sorts of shapes and . . . just as they had fallen, and it seems like they have nearly all been shot in the head, and a great number of them have their skulls bursted open and their brains running out, quite a number that way. I have seen many dead men, and seen them wounded and crippled in various ways, have seen their limbs cut off, but I never saw anything before that made me sick, like looking at the brains of these men did. I do believe that if a soldier could be made to faint, that I would have fainted if I had not passed on and got out of that place as soon as I did - We learn thru Col. Wilkes that we killed 703 dead on the ground, and captured near 350 prisoners."

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Sunday, May 25, 2014

150 Years Ago Today - Battle of New Hope Church

After the clash at Resaca on May 15, Sherman continued moving south. Avoiding the well defended Allatoona Pass, the Union commander left his communications with the railroad and headed southwest. Johnson's Confederates continued to give resistance, rapidly throwing up earthwork defenses when possible.

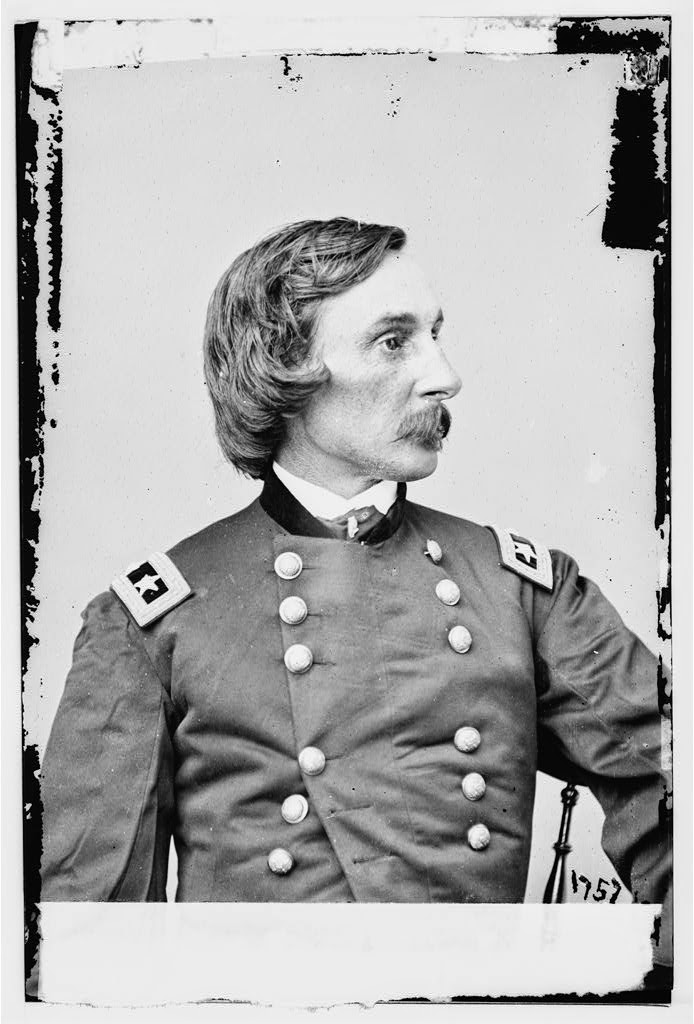

On May 25, Union forces under Gen. Joseph Hooker ran into rebels from Gen. A. P. Stewart's Division near New Hope Church. One of the Union soldiers engaged that day was Corporal Edmund R. Brown of the 27th Indiana Infantry Regiment, which was in Thomas H. Ruger's (pictured) brigade. Of the fighting here Brown wrote:

"Suddenly, a most terrific fire of both musketry and artillery was opened upon us. We were at the foot of, or passing up, a gentle slope. On the crest, barely a few rods distant, was a long parapet blazing with [gun] fire and and death. The undergrowth was so dense that few, if any, of us were aware of what we were coming to, until the storm burst. It came with so little premonition on our part, that it almost seemed as if the position had been purposely masked, and that we had been decoyed to our death. This impression may have been prevailed among us to some extent afterwards. It is scarcely necessary to say that such was not the case. The timber which, for lack of time and means, the enemy could not cut away, had, until now, prevented them from seeing us, as well as us from seeing them.

It would be impossible to conceive of a more appalling, terrifying, if not fatal, rain of lead and iron than this one, which our line met at New Hope Church. The canister and case shot in particular, hissed, swished and sung around and among us, barking the trees, glancing and bounding from one to the other, ripping up the ground, throwing dirt in our faces and rolling at our feet, until those not hit by them were ready to conclude that they surely would be hit. Milton's words were none too strong to apply to the situation:

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

On May 25, Union forces under Gen. Joseph Hooker ran into rebels from Gen. A. P. Stewart's Division near New Hope Church. One of the Union soldiers engaged that day was Corporal Edmund R. Brown of the 27th Indiana Infantry Regiment, which was in Thomas H. Ruger's (pictured) brigade. Of the fighting here Brown wrote:

"Suddenly, a most terrific fire of both musketry and artillery was opened upon us. We were at the foot of, or passing up, a gentle slope. On the crest, barely a few rods distant, was a long parapet blazing with [gun] fire and and death. The undergrowth was so dense that few, if any, of us were aware of what we were coming to, until the storm burst. It came with so little premonition on our part, that it almost seemed as if the position had been purposely masked, and that we had been decoyed to our death. This impression may have been prevailed among us to some extent afterwards. It is scarcely necessary to say that such was not the case. The timber which, for lack of time and means, the enemy could not cut away, had, until now, prevented them from seeing us, as well as us from seeing them.

It would be impossible to conceive of a more appalling, terrifying, if not fatal, rain of lead and iron than this one, which our line met at New Hope Church. The canister and case shot in particular, hissed, swished and sung around and among us, barking the trees, glancing and bounding from one to the other, ripping up the ground, throwing dirt in our faces and rolling at our feet, until those not hit by them were ready to conclude that they surely would be hit. Milton's words were none too strong to apply to the situation:

'Fierce as ten furies and terrible as hell'

Yet the boys only cheered the more defiantly, and, while loading and firing with all their might, gained ground to the front. Just in the hottest of the fight there was a downpour of rain. In the damp and murky atmosphere the smoke from our muskets, instead of rising and disappearing, settled around us and accumulated in thick clouds. The woods in which we were immersed became [weird] and spectral. Eventually it became almost a battle in the dark. When we were finally brought to a standstill it was impossible to make out with any distinctness even the position of the enemy. Our aim was directed almost wholly at the flashes and reports of their guns."

Fighting along this line continued with battles at Pickett's Mill (May 27) and Dallas (May 28). The terrible fighting at Kennesaw Mountain was less than month away and the prize of Atlanta was only a few tough miles ahead. But many lives would be expended in attacking and defending the important rail city.

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Saturday, May 24, 2014

Antebellum White Kentuckians and their Perceptions of Free Blacks

In doing my research on Kentucky's antebellum black barbers I have found numerous references that show white Kentuckians' disdain for free people of color. Despite the fact that the vast majority of free blacks were hard-working and law abiding, whites consistently read in the newspapers about those few who created stereotypes for the many.

The majority of white Kentuckians believed that slavery was the best social system for both races. Slavery allowed whites to socially control blacks and coerce their labor. Whites believed that if blacks were without the controlling influence of slave owners they would not work for their self support, would resort to theft and other crimes to survive, and thus become a unnecessary burden on society.

The first three short articles posted here ran in the Louisville Daily Courier in the summer of 1859 (all within days of each other), and concerned a free black barber named Alexander Hatfield. Hatfield is listed in the 1850 census in Louisville as 26 year old "black" barber. Hatfield is missing from the 1860 census. It could be that his criminal activity finally caught up with him and landed him in the "penitentiary," as the above article hopefully suggests.

Hatfield's stay in the jail for the accused crime of stealing $25 was short-lived as there was insufficient evidence for a conviction. Hatfield's apparent history of criminal activity obviously influenced the newspaper's perception of whether he was guilty or innocent.

Hatfield's bad decisions appear to have continued. His alleged theft and misuse of a horse and buggy brought more trouble his way and provided the newspaper with more fodder to print, which only added to the negative perception of free blacks.

The speculative accusations against free blacks during this era have not ceased to amaze me. By merely being next door to a home that was robbed of some articles of clothing, individuals that attended a "negro ball" were thought to have been the perpetrators. In the court of public opinion free blacks seem to have had to prove their innocence as they were always assumed to be guilty.

A black barbershop was the setting for another story that ran in the Louisville Daily Democrat in the summer of 1859. This story does not specifically say if the perpetrator, John Jordan, was a barber, but it is likely that he was as he apparently took the patron's money while brushing his clothing, presumably after cutting the man's hair. There is a 22 year old "mulatto" John Jordan listed as a barber in Frankfort in 1860. Perhaps this incident in Louisville encouraged Jordan to seek a new beginning in a new location.

Yet another black barber was suspected of stealing from a customer in the above story. Although the white customer, William Bosley, could have lost or had his wallet stolen at any time during in his travels, he suspected black barber William Swede. Swede, a native of Ohio, is listed in the 1860 census as a 26 year old "mulatto" barber with only $50 in personal property. Although Swede was eventually absolved of the charge, stories such as this only added to whites' beliefs that free blacks were a trouble making burden on society.

A couple of references that I found in the 1860 census from Greenup County, Kentucky, again showed how whites often perceived free blacks. It is not know if Edmund Derican was indeed a deadbeat, and thus the census taker's label of "worthless" was correct. However, the line where "worthless" is noted was intended to list the person's occupation. Was it necessary to provide such an opinion, whether he deserved or not?

Similarly, and probably family related, was the notation on Edward Derikin's census. With such similar first and last names, and probably spelled phonetically, Edward and Edmund were likely brothers. Only 10 years different in age and with both listed as being "black," Edward received the census taker's labeled occupation of "doing nothing."

It is interesting that Edward's wife, Henny, and son Doctor, were both not listed as black or mulatto, which seemingly indicates they were white. Did the census taker just not note their color, or was Edward living with a white wife and step son? It is also intriguing that Edmund and Edward both had sons named Doctor, and that the boys were only one year apart in age. That leads me to suspect that Edward's son was not a step son but his real son, and that either his complexion was so light as not be to noted or that the census taker just overlooked noting him (and possibly his mother) as black or mulatto. Regardless, to me, these occupation notations provide yet more evidence of antebellum white Kentuckians' perceptions of free black as being less than worthy citizens and best suited to slavery.

Friday, May 23, 2014

A Black Barber and Bleeding Kansas

The above short article (and attempt at humor) ran in the January 25, 1859 edition of the Louisville Daily Courier. I found it intriguing not only because it involved an enslaved barber, but it also demonstrates how closely people followed national events in the mid-nineteenth century. Because, if you do not know the story behind the last claim made, you will not get the humor.

Here is an attempt at explanation: The territorial governor of Kansas at the time, Samuel Medary, goes into a Lecompton, Kansas, barbershop and states that he would like to be shaved on monthly credit. The black barber states that he is not sure that is wise on his part. The governor asks why not, and the barber states that due to the fact that so many territorial governors have come and gone since the state received territory status the governor may leave office before the end of the month when payment would be due.

Kansas did in fact run through territorial governors at a rapid pace. And, no wonder why - violence roiled the area for its early years as settlers fought over whether the state would enter the Union with slavery or not.

Here's a list of the territorial governors that took office starting when the region became a territory in 1854:

Andrew H. Reeder - July 1854 to August 1855

Wilson Shannon - September 1855 to August 1856

John W. Geary - September 1856 to March 1857

Robert J. Walker - May 1857 to December 1857

James Denver - December 1857 to November 1858

Samuel Medary - December 1858 to December 1860

George Bebee - December 1860 to February 1861

In between these men's terms were several acting territorial governors (some of which served multiple short terms), which only added to the dizzying changes in leadership in the Sunflower State's early history. Kansas finally received statehood in February 1861 with Charles Robinson as governor.

Tuesday, May 20, 2014

Free Men of Color and the Limits of Freedom

In an 1863 interview Louisville black barber Washington Spradling explained that there were limits to his freedom. He expressed frustration at racial prejudice as it related to police harassment, taxes, and the limits on travel, among other things.

Free men of color understood how important it was to have white men vouch for them; the more wealthy and recognized the better. When free blacks wished to travel it was well known that carrying free papers or at least of letter of introduction was helpful in case certain situations arose.

The above letter is included among the several pieces of surviving papers that belonged to Lexington free black barber Samuel A. Oldham. It appears to have been written by Lexington attorney Leslie Combs. Combs was a War of 1812 officer, member of the Kentucky legislature, Transylvania University trustee, and well respected Lexingtonian. It reads:

Lexington Oct 14/49

Samuel Oldham the bearer hereof is a

freeman of excellent conduct and character – by trade – a Barber – about 45 to

50 years of age – of middle size – yellow complexion, tho not a mulatto –

middle size – rather inclined to fullness - & flesh – He proposes visiting

Ohio & other portions on pleasure or business & is entitled to kind

treatment & consideration wherever he may be –

Signed under our hands

Leslie Combs

O.F. Payne, Mayor

James A. Grinstead

J. G. Chiles

As can be seen, Oldham had not only Combs give an endorsement, but also other prominent white men in Lexington, including the mayor, O.F. Payne. It was likely through his barber business that Oldham came into contact with such community notables. Oldham's skills, attention to customers' needs, entrepreneurship, and prosperity must have made a positive impression over the years on these men, who pledged their reputation for Oldham.

However, like Washington Spradling, Oldham must have felt extreme frustration at this necessity. For a man who had accomplished so much through hard work, frugality, and wise business sense to have to shelve a measure of the independence he had earned and turn to others for a letter of good conduct and character must have been especially exasperating.

Sunday, May 18, 2014

Miscegenation or the Millennium of Aboltionism

The second in a series of anti-Lincoln

satires by Bromley & Co. This number was deposited for copyright on July 1,

1864. The artist conjures up a ludicrous vision of the supposed consequences of

racial equality in America in this attack on the Republican espousal of equal

rights.

The scene takes place in a park-like setting with a fountain in the

shape of a boy on a dolphin and a large bridge in the background. A black woman

(left), "Miss Dinah, Arabella, Aramintha Squash," is presented by

abolitionist senator Charles Sumner to President Lincoln. Lincoln bows and

says, "I shall be proud to number among my intimate friends any member of

the Squash family, especially the little Squashes." The woman responds,

"Ise 'quainted wid Missus Linkum I is, washed for her 'fore de hebenly

Miscegenation times was cum. Dont do nuffin now but gallevant 'round wid de

white gemmen! . . . "

A second mixed couple sit at a small table (center)

eating ice cream. The black woman says, "Ah! Horace its-its-its bully

'specially de cream." Her companion, Republican editor Horace Greeley,

answers, "Ah! my dear Miss Snowball we have at last reached our political

and social Paradise. Isn't it extatic?" To the right a white woman

embraces a black dandy, saying, "Oh! You dear creature. I am so agitated!

Go and ask Pa." He replies, "Lubly Julia Anna, name de day, when

Brodder Beecher [abolitionist clergyman Henry Ward Beecher] shall make us

one!"

At the far right a second white woman sits on the lap of a plump

black man reminding him, "Adolphus, now you'll be sure to come to my

lecture tomorrow night, wont you?" He assures her, "Ill be there

Honey, on de front seat, sure!" A German onlooker (far right) remarks,

"Mine Got. vat a guntry, vat a beebles!" A well-dressed man with a

monocle exclaims, "Most hextwadinary! Aw neva witnessed the like in all me

life, if I did dem me!" An Irishwoman pulls a carriage holding a black

baby and complains, "And is it to drag naggur babies that I left old

Ireland? Bad luck to me."

In the center a Negro family rides in a carriage

driven by a white man with two white footmen. The father lifts his hat and

says, "Phillis de-ah dars Sumner. We must not cut him if he is

walking." Their driver comments, "Gla-a-ang there 240s! White driver,

white footmen, niggers inside, my heys! I wanted a sitiwation when I took this

one."

The term "miscegenation" was coined during the 1864

presidential campaign to discredit the Republicans, who were charged with

fostering the intermingling of the races. In the lower margin are prices and

instructions for ordering various numbers of copies of the print. A single copy

cost twenty-five cents "post paid."

Image and interpretation courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Saturday, May 17, 2014

Not Exactly Advertisements

While I have found a plethora of antebellum black barber advertisements in newspapers all across Kentucky, only a couple have taken the form of short articles; both of which were found in a Louisville newspaper. The above mentioned that William Spradling, son of the wealthy and well-known Louisville barber Washington Spradling, had moved his business. This notice ran in the November 11, 1855, issue of the Daily Louisville Democrat.

Like normal advertisements it gives the location of Spradling's new shop - or in this case "stand" - but unlike most other advertisements, it offers an endorsement, which seems objective.

A notice similar to that of Spradling's in 1855 is show above, for William Scroggins' new shop. Like Spardling's article, Scroggins' notice provides the location of the new shop and offers an encouraging endorsement. It, too, ran in the Daily Louisville Democrat, but in the October 22, 1858 edition.

Since locating them, I have been wondering if these notices were paid for by the barber, who preferred a different format than a traditional box ad, or if they were used by the newspaper for column filler space when they received word that a business was moving or changing owners. It seems to me that ads such as these would get lost among the numerous other similar looking short articles, but then again, I suppose the same argument could be made for the more common box advertisements, too.

Regardless, it appears that Kentucky's antebellum black barbers moved their businesses in attempt to find potentially more customers and thus increase their revenue and profits. If these advertisements were intentional marketing on the part of the shop owners, it shows the barbers' level of business acumen. If they were merely space filler from the newspapers, I am sure the barbers appreciated the free promotion.

Wednesday, May 14, 2014

One Soldier's Resaca - 150 Years Ago Today

As the Confederates crawfished toward Atlanta, being ever pushed and flanked by Sherman's legions, a fight erupted at Resaca. Entrenched and on a commanding ridge, the Rebels were attacked on May 14. The battle ended up being the largest in Georgia during the Civil War.

One of the soldiers blunting the Union attacks was Sergeant James L. Cooper of the 20th Tennessee Infantry. The 20th was in Tyler's Brigade, which was part of William B. Bate's (pictured) Division in Hardee's Corps. Cooper had been wounded in the fighting at Chattanooga the previous November, but had recovered enough to rejoin the 20th for the spring campaign.

In the fighting at Resaca, Cooper took a serious wound to the neck. Here is what he wrote about his bad day (paragraphs added for readability):

"During the night of the 13th we worked at the fortification, and on the 14th, about 12 o'clock the enemy advanced in force, and began a heavy attack. We repulsed several assaults, and about three o'clock we were sitting behind our rail piles waiting for another charge. At this time I was shot by a sharpshooter who had crawled within a short distance from the works. I was sitting down, closely wedged in by my companions on every side, for the position was very exposed, when all at once I felt a terrible shock and with a sinking consciousness of dying, became insensible. In an instant I recovered my senses, and found myself with my head fallen forward on my breast, and without power to move a muscle. I could hear the blood of the wound pattering on the ground, and thinking I was dying, almost thought I saw eternity opening before me. I felt so weak, so powerless, that I did not know whether I was dead or not.

The noise of the battle seemed miles away, and my thoughts were all pent up in my own breast. My system was paralized, but in my mind was terribly active. My head was full of a buzzing din, and the sound of that blood falling on the ground seemed louder than a cataract. I finally recovered the use of my tongue and still thinking I was dying, told the boys that it was no use to anything for me, that I was a dead man. All this time I could hear remarks around me, which, although very complimentary, were not at all consoling. When first shot one man exclaimed, 'By God, they killed a good one that time,' another 'My God, Cooper's killed,' and several other equal to these.

Finally Capt. Lucas directed the man directly behind me, J. Gee, of Co. D to catch hold of the wound and try to stop the blood. To my surprise he succeeded, and in half an hour, or less time, I had sufficiently recovered by strength to start to the rear. I walked half a mile through perfect showers of balls, and reached the ambulance perfectly exhausted. I was then taken to the hospital, and after being exposed to some danger from shells, that night we were taken to the railroad, and then to Atlanta.

I suffered some from my wounds before I reached Atlanta but was well cared for when I was taken to the hospitals. I was about the most forsaken looking object that came to that place, I know, and when I got off the cars felt pretty sheepish. The entire "crystal of my pants" was gone, and I was covered with blood and dirt, so I had reasons for feeling sheepish, being exposed to the sharp eyes of about four hundred ladies. If their eyes were sharp, their hands and hearts were tender as I soon experienced."

Cooper was yet again back in service within two months, but was fortunate to land a position on the brigade staff to finish out the war. He fortunately survived the conflict and was able to return home to Nashville, where he excelled as a farmer and cattle breeder.

One of the soldiers blunting the Union attacks was Sergeant James L. Cooper of the 20th Tennessee Infantry. The 20th was in Tyler's Brigade, which was part of William B. Bate's (pictured) Division in Hardee's Corps. Cooper had been wounded in the fighting at Chattanooga the previous November, but had recovered enough to rejoin the 20th for the spring campaign.

In the fighting at Resaca, Cooper took a serious wound to the neck. Here is what he wrote about his bad day (paragraphs added for readability):

"During the night of the 13th we worked at the fortification, and on the 14th, about 12 o'clock the enemy advanced in force, and began a heavy attack. We repulsed several assaults, and about three o'clock we were sitting behind our rail piles waiting for another charge. At this time I was shot by a sharpshooter who had crawled within a short distance from the works. I was sitting down, closely wedged in by my companions on every side, for the position was very exposed, when all at once I felt a terrible shock and with a sinking consciousness of dying, became insensible. In an instant I recovered my senses, and found myself with my head fallen forward on my breast, and without power to move a muscle. I could hear the blood of the wound pattering on the ground, and thinking I was dying, almost thought I saw eternity opening before me. I felt so weak, so powerless, that I did not know whether I was dead or not.

The noise of the battle seemed miles away, and my thoughts were all pent up in my own breast. My system was paralized, but in my mind was terribly active. My head was full of a buzzing din, and the sound of that blood falling on the ground seemed louder than a cataract. I finally recovered the use of my tongue and still thinking I was dying, told the boys that it was no use to anything for me, that I was a dead man. All this time I could hear remarks around me, which, although very complimentary, were not at all consoling. When first shot one man exclaimed, 'By God, they killed a good one that time,' another 'My God, Cooper's killed,' and several other equal to these.

Finally Capt. Lucas directed the man directly behind me, J. Gee, of Co. D to catch hold of the wound and try to stop the blood. To my surprise he succeeded, and in half an hour, or less time, I had sufficiently recovered by strength to start to the rear. I walked half a mile through perfect showers of balls, and reached the ambulance perfectly exhausted. I was then taken to the hospital, and after being exposed to some danger from shells, that night we were taken to the railroad, and then to Atlanta.

I suffered some from my wounds before I reached Atlanta but was well cared for when I was taken to the hospitals. I was about the most forsaken looking object that came to that place, I know, and when I got off the cars felt pretty sheepish. The entire "crystal of my pants" was gone, and I was covered with blood and dirt, so I had reasons for feeling sheepish, being exposed to the sharp eyes of about four hundred ladies. If their eyes were sharp, their hands and hearts were tender as I soon experienced."

Cooper was yet again back in service within two months, but was fortunate to land a position on the brigade staff to finish out the war. He fortunately survived the conflict and was able to return home to Nashville, where he excelled as a farmer and cattle breeder.

Tuesday, May 13, 2014

More on Black Barber Wallace Cowan

Friends are great, aren't they? The other day a colleague at work and I were talking about my research on antebellum black barbers and a day later he shared an image that provided me with more information about one of the men we had talked about.

A few weeks ago I posted a short article that I had found describing an incident involving Louisville black barber Wallace Cowan in 1859. But before moving to Kentucky's largest city, Cowan started his barber occupation in Danville.

The document (above) that was shared with me was Cowan's deed of emancipation, which was filed by his owner Elizabeth Cowan of Boyle County in 1848. Cowan purchased his freedom for $300. It is unknown how he raised the money to buy his freedom, but it possible that he was an enslaved barber and used funds from that occupation to gain his liberty, as only two years later he was listed in the 1850 census as a free man of color barber.

Interestingly, Cowan was listed as 28 years old in the 1848 manumission papers, and 28 years old again in 1850. In that mid-century census, Cowan and another free man of color, Thomas Hall, a 42 year old stone mason, both resided in the household of Frances and Lucy Sarcene. The deed of emancipation also provided a description of Cowan; albeit a brief one. He was described as "of black complexion, with wide space between the front teeth of the upper jaw."

Between 1850 and 1860 Cowan moved to Louisville. This does not appear to be all that unusual for free black barbers. It appears that there was an attraction for barbers to make the move to larger markets during their careers. Perhaps in their thinking larger markets meant more customers and thus potentially more income. Surely they understood larger markets meant more competition too, but maybe they perceived that the future benefits outweighed the risks.

In 1860, Cowan was living in Louisville's Fourth Ward with his wife Margaret, who was 27 years old, and daughter Elizah, who was 10 years old. He claimed $400 in personal property. Cowan's age was given as 33.

In 1870, Wallace was listed as 40. Margaret was noted as being a 30 year old house keeper. A three year old son, Eugene, and 60 year old Sallie Campbell, a house servant, were also in Cowan's household. Elizah may have married between 1860 and 1870 and left the household.

In 1880, Wallace Cowan was still a barber, now noted as 56 years old. Only 43 year old Martha (perhaps still the same wife Margaret, noted on the other census reports, or possibly an entirely different woman) and Wallace were in the Cowan home.

Cowan apparently died on May 9, 1894, of "paralysis," which probably meant he has suffered a stroke. He was noted as being 75 years old. Despite the differences in the reports of Cowan's age over the 1850, 1860, 1870, and 1880 censuses, it appears that he was born about 1819 or 1820, as the first surviving document (his deed of manumission) and the last surviving document (his death report) corroborate those dates.

Monday, May 12, 2014

Fierce Fighting at the Mule Shoe - 150 Years Ago Today

After the bout in the Wilderness, the Army of the Potomac and the Army of Northern Virginia tangled again near Spotsylvania Courthouse. On chosen ground, the Confederates erected a significant system of earthworks, part of which included a jutting salient that was nicknamed the "Mule Shoe," as it resembled an iron hoof protector for that particular beast of burden.

Union attacks on the Mule Shoe on May 10 and 12 resulted in some of the most horrific combat of the Civil War. Not only was it particularly fierce; it was also in a steady downpour. On May 12 Union troops actually breeched the Mule Shoe. Among the Confederate units pouring into the position to counterattack was the South Carolina brigade of Samuel McGowan (pictured).

Lt. J. F. J. Caldwell of the 1st South Carolina wrote about what he experienced:

"About ten o'clock, our brigade was suddenly ordered out of the works, detached from the rest of the division, and marched back from the line, but bearing towards the left. The fields were soft and muddy, the rains quite heavy. Nevertheless, we hurried on, often at the double-quick. Before long, shells passed over our heads, and musketry became plainly audible in front. Our pace was increased to a run. Turning to the right, as we struck an interior line of works, we bore directly for the firing.

We were now along Ewell's line. The shell came thicker and nearer, frequently striking close at our feet, and throwing mud and water high into the air. The rain continued. As we panted up the way, Maj. Gen. Rodes, of Ewell's corps, walked up to the road-side, and asked what troops we were. 'McGowan's South Carolina brigade,' was the reply. 'There are no better soldiers in the world than these!' cried he to some officers about him. We hurried on, thinking more of him and more of ourselves than ever before.

Reaching the summit of an open hill, where stood a little old house and its surrounding naked orchard, we were fronted and ordered forward on the left of the road. The Twelfth regiment was on the right of our line, then the First, then the Thirteenth, the the Rifles, the the Fourteenth. Now we entered the battle. There were two lines of works before us; the first, or inner line, from a hundred and fifty to two hundred yards from us, the second, or outer line, perhaps a hundred yards beyond it, and parallel with it. There were troops in the outer line, bu the inner one only what appeared to be masses without organization. The enemy were firing in front of the extreme right of the brigade, and their balls came obliquely down our line; but we could not discover, on account of the woods about the point of firing, under what circumstances the battle was held. There was a good deal of doubt as to how far we should go, or in what direction. At first it was understood that we should throw ourselves into the woods, where the musketry was; but, somehow, this idea changed to the impression that we were to move straight forward - which would bring only about the extreme right regiment to the chief point of attack. The truth is, the road by which we had come was not at all straight, which mad the right of the line front much father north than the rest, and the fire was too hot for us to wait for us to wait of the long, loose column to close up, so as to make an entirely orderly advance. More than all this, there was a death-struggle ahead, which must be met instantly.

We advanced at the double-quick, cheering loudly, and entered the inner works. Whether by order or tacit understanding, we halted here, except the Twelfth regiment, which was the right of the brigade. That moved at once tot he outer line, and threw itself with it wonted impetuosity, into the heart of the battle. . . .

. . . About the time we reached the inner line, General McGowan was wounded by a Minie ball, in the right arm, and forced to quit the field. Colonel Brockman, senior colonel present, was also wounded, and Colonel J. N. Brown, of the Fourteenth regiment, assumed command, then or a little later. The four regiments - First, Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Rifles (the Twelfth had passed on to the outer line) - closed up and arranged their lines. Soon the order was given to advance to the outer line. We did so, with a cheer and at the double-quick, plunging through mud knee-deep, and getting in as best we could. Here, however, lay Harris' Mississippi brigade. We were ordered to close to the right. We moved by the flank up the works, under the fatally accurate fire of the enemy, and ranged ourselves along the intrenchment. The sight we encountered was not calculated to encourage us. The trenches, dug on the inner side, were almost filled with water. Dead men lay on the surface of the ground and in the pools of water. The wounded bled and groaned, stretched or huddled in ever attitude of pain. The water was crimsoned with blood. Abandoned knapsacks, guns and accouterments, with ammunition boxes, were scattered all around. In the rear, disabled caissons stood and limbers of guns. The rain poured heavily, and an incessant fired was kept upon us from front and flank. The enemy still held the works on the right of the angle, and fired across the traverses. Nor were these foes easily seen. They barely raised their heads above the logs, at the moment of firing. It was plainly a question of bravery and endurance now.

We entered upon the task with all our might. Some fired at the line lying in front, on the edge of the ridge before described; others kept down the enemy lodged in the traverses to the right. At one or two places, Confederates and Federals were only separated by the works, and the latter not a few times reached their guns over and fired right down upon the heads of the former."

A new line of entrenchments was formed across the base of the Mule Shoe, which thwarted Grant's gains of May 12, and made him consider another alternative than battering Lee's army. The Army of the Potomac had suffered over 18,000 casualties in the fighting at Spotsylvania. Those numbers combined with almost another 18,000 at the Wilderness was a terrible toll in just a few weeks time. But he would not retreat. More deadly fighting was just ahead.

Union attacks on the Mule Shoe on May 10 and 12 resulted in some of the most horrific combat of the Civil War. Not only was it particularly fierce; it was also in a steady downpour. On May 12 Union troops actually breeched the Mule Shoe. Among the Confederate units pouring into the position to counterattack was the South Carolina brigade of Samuel McGowan (pictured).

Lt. J. F. J. Caldwell of the 1st South Carolina wrote about what he experienced:

"About ten o'clock, our brigade was suddenly ordered out of the works, detached from the rest of the division, and marched back from the line, but bearing towards the left. The fields were soft and muddy, the rains quite heavy. Nevertheless, we hurried on, often at the double-quick. Before long, shells passed over our heads, and musketry became plainly audible in front. Our pace was increased to a run. Turning to the right, as we struck an interior line of works, we bore directly for the firing.

We were now along Ewell's line. The shell came thicker and nearer, frequently striking close at our feet, and throwing mud and water high into the air. The rain continued. As we panted up the way, Maj. Gen. Rodes, of Ewell's corps, walked up to the road-side, and asked what troops we were. 'McGowan's South Carolina brigade,' was the reply. 'There are no better soldiers in the world than these!' cried he to some officers about him. We hurried on, thinking more of him and more of ourselves than ever before.

Reaching the summit of an open hill, where stood a little old house and its surrounding naked orchard, we were fronted and ordered forward on the left of the road. The Twelfth regiment was on the right of our line, then the First, then the Thirteenth, the the Rifles, the the Fourteenth. Now we entered the battle. There were two lines of works before us; the first, or inner line, from a hundred and fifty to two hundred yards from us, the second, or outer line, perhaps a hundred yards beyond it, and parallel with it. There were troops in the outer line, bu the inner one only what appeared to be masses without organization. The enemy were firing in front of the extreme right of the brigade, and their balls came obliquely down our line; but we could not discover, on account of the woods about the point of firing, under what circumstances the battle was held. There was a good deal of doubt as to how far we should go, or in what direction. At first it was understood that we should throw ourselves into the woods, where the musketry was; but, somehow, this idea changed to the impression that we were to move straight forward - which would bring only about the extreme right regiment to the chief point of attack. The truth is, the road by which we had come was not at all straight, which mad the right of the line front much father north than the rest, and the fire was too hot for us to wait for us to wait of the long, loose column to close up, so as to make an entirely orderly advance. More than all this, there was a death-struggle ahead, which must be met instantly.

We advanced at the double-quick, cheering loudly, and entered the inner works. Whether by order or tacit understanding, we halted here, except the Twelfth regiment, which was the right of the brigade. That moved at once tot he outer line, and threw itself with it wonted impetuosity, into the heart of the battle. . . .

. . . About the time we reached the inner line, General McGowan was wounded by a Minie ball, in the right arm, and forced to quit the field. Colonel Brockman, senior colonel present, was also wounded, and Colonel J. N. Brown, of the Fourteenth regiment, assumed command, then or a little later. The four regiments - First, Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Rifles (the Twelfth had passed on to the outer line) - closed up and arranged their lines. Soon the order was given to advance to the outer line. We did so, with a cheer and at the double-quick, plunging through mud knee-deep, and getting in as best we could. Here, however, lay Harris' Mississippi brigade. We were ordered to close to the right. We moved by the flank up the works, under the fatally accurate fire of the enemy, and ranged ourselves along the intrenchment. The sight we encountered was not calculated to encourage us. The trenches, dug on the inner side, were almost filled with water. Dead men lay on the surface of the ground and in the pools of water. The wounded bled and groaned, stretched or huddled in ever attitude of pain. The water was crimsoned with blood. Abandoned knapsacks, guns and accouterments, with ammunition boxes, were scattered all around. In the rear, disabled caissons stood and limbers of guns. The rain poured heavily, and an incessant fired was kept upon us from front and flank. The enemy still held the works on the right of the angle, and fired across the traverses. Nor were these foes easily seen. They barely raised their heads above the logs, at the moment of firing. It was plainly a question of bravery and endurance now.

We entered upon the task with all our might. Some fired at the line lying in front, on the edge of the ridge before described; others kept down the enemy lodged in the traverses to the right. At one or two places, Confederates and Federals were only separated by the works, and the latter not a few times reached their guns over and fired right down upon the heads of the former."

A new line of entrenchments was formed across the base of the Mule Shoe, which thwarted Grant's gains of May 12, and made him consider another alternative than battering Lee's army. The Army of the Potomac had suffered over 18,000 casualties in the fighting at Spotsylvania. Those numbers combined with almost another 18,000 at the Wilderness was a terrible toll in just a few weeks time. But he would not retreat. More deadly fighting was just ahead.

Thursday, May 8, 2014

Meanwhile in Georgia. . . .

While things were heating up in Virginia, Sherman was on the move in Georgia. In the weeks before his campaign started "Uncle Billy" wrote to his his wife that "All that has gone before is mere skirmishing. The war now begins, and with heavy well-disciplined masses the issue must be settled in hard fought battles." Hard fought battles there would be, along with a significant amount of maneuvering.

On May 8, 1864, a clash appeared imminent at Dug Gap, near Dalton. Preparing for that fight was Lt. Lot D. Young of the 4th Kentucky Infantry (CSA). The 4th Kentucky was one of the regiments of the Orphan Brigade - the Bluegrass State Confederates who were not to go home until the war was over. The Orphans had lost their commander Gen. Benjamin Hardin Helm at Chickamauga back in September, but the battle-hardened veterans were now led by Gen. Joseph H. Lewis (pictured).

In the mountains of northern Georgia, Lt. Young and Orphans watched the Union forces gather. He wrote:

"While contemplating the future, news came that the enemy were now moving Daltonward. We indulged the hope and wondered whether Sherman would undertake to force the pass in Rockyface Mountain through which the railroad and wagon road both ran. We thought of Leonidas and his Spartans and hoped for an opportunity to imitate and if possible to eclipse that immortal event at Thermopylae. But not so the wily Sherman. That "old fox" was too cunning to be caught in that or any other trap.

We were ordered out to meet him and took position in the gap and on the mountain, from which we could see extending for miles his grand encampment of infantry and artillery, the stars and stripes floating from every regimental brigade, division, and corps headquarters and presenting the greatest panorama I ever beheld. Softly and sweetly the music from their bands as they played the national airs were wafted up and over the summit of the mountain. "Hail Columbia," "America" and "The Star Spangled Banner" sounded sweeter than I had ever before heard them, and filled my soul with feelings that I could not describe or forget. It haunted me for days, but never shook my loyalty to the Stars and Bars or relaxed my efforts in behalf of our cause."

Lt. Young, like so many other soldiers, did not make it though the following months of trying combat without wounds. On August 31, while fighting at Jonesboro, Georgia, he received a leg wound, which ended his service.

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

On May 8, 1864, a clash appeared imminent at Dug Gap, near Dalton. Preparing for that fight was Lt. Lot D. Young of the 4th Kentucky Infantry (CSA). The 4th Kentucky was one of the regiments of the Orphan Brigade - the Bluegrass State Confederates who were not to go home until the war was over. The Orphans had lost their commander Gen. Benjamin Hardin Helm at Chickamauga back in September, but the battle-hardened veterans were now led by Gen. Joseph H. Lewis (pictured).

In the mountains of northern Georgia, Lt. Young and Orphans watched the Union forces gather. He wrote:

"While contemplating the future, news came that the enemy were now moving Daltonward. We indulged the hope and wondered whether Sherman would undertake to force the pass in Rockyface Mountain through which the railroad and wagon road both ran. We thought of Leonidas and his Spartans and hoped for an opportunity to imitate and if possible to eclipse that immortal event at Thermopylae. But not so the wily Sherman. That "old fox" was too cunning to be caught in that or any other trap.

We were ordered out to meet him and took position in the gap and on the mountain, from which we could see extending for miles his grand encampment of infantry and artillery, the stars and stripes floating from every regimental brigade, division, and corps headquarters and presenting the greatest panorama I ever beheld. Softly and sweetly the music from their bands as they played the national airs were wafted up and over the summit of the mountain. "Hail Columbia," "America" and "The Star Spangled Banner" sounded sweeter than I had ever before heard them, and filled my soul with feelings that I could not describe or forget. It haunted me for days, but never shook my loyalty to the Stars and Bars or relaxed my efforts in behalf of our cause."

Lt. Young, like so many other soldiers, did not make it though the following months of trying combat without wounds. On August 31, while fighting at Jonesboro, Georgia, he received a leg wound, which ended his service.

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Tuesday, May 6, 2014

The Battle of the Wilderness - May 6

Day two of fighting in the Wilderness witnessed some of the Civil War's most desperate combat. The following account was left by Private Henry H. Frary, a former farmer who had been drafted into Union service 10 months before. Frary was a member of the 97th New York Infantry, which was in Gen. Henry Baxter's Brigade, Robinson's Division of Warren's (pictured) V Corps.

"On the morning of the 6th, firing began as the first light of day showered through the trees. Soon after sunrise a charge was ordered along the whole line covered by the 5th corps. As we drove the enemy from the line they had occupied the evening before, we could see the evidence that our fire had been effective as there were dead men laying all about. Just in the rear of a large tree were six bodies fairly piled one on another.

Just before we reached the plank road, I was struck by a spent ball on the left knee, cutting through the pants and flesh, striking my knee cap, cracking it, and causing me to measure my length on the ground. On getting up, and finding that I was all together, I continued on with the line. We struck the [Orange Plank] road at an angle and wheeled slightly to the right, still driving the enemy. Men on both sides were falling, either a question of a little time when we would entirely destroy each other. Finally we came to a halt as we reached a line of their works and they opened up a battery from front and right oblique on us, at close range, with terrible effect. One shell which exploded just to my right caused three deaths and three others were wounded. Two of the dead were twin brothers by the name of Fisher.

Just after that, as I was with right knee on the ground, resting left elbow on left knee, and aiming my Enfield at Johnny standing at the right end of our ambulance, a shell exploded above and so close to my head that I heard that rending of the iron of the shell. A piece of it struck my gun on the stock, knocking it out of my hands, and hit the side of my shoe as it reached the ground. At this same instant, I felt that my whole left side was torn out. It was one awful terrible agonizing sensation as though all creation had fallen upon me, crushing and tearing my body apart, piece by piece. My first thought was that the piece of shell had gone through my body. The concussion from the shell had partly thrown me back so that when I straightened up partially, the blood gushed out of my mouth and nose as though pumped.

My captain ordered two men, W. H. Gray and Columbus W. Ford, to carry me back to the rear and stay with me. We started back, they carrying me as best they could, by holding me up under my arms. That was agonizing to me so begged them to lay me down so I could die in peace. Even then I was wondering that I could be conscious when I was torn open as I supposed I was. They sat me down by the side of the road. We could see and hear shells come tearing down the road and through the woods. I was still bleeding from nose and mouth. With others' help they boys carried me back a ways. When I was becoming faint, I begged them to lay me down, which they did. I bid them goodby as my vision dimmed, supposing that for me it was the last of earth. Thoughts of my wife and children back at home came to mind. With a mental power that God would care for them, I became unconscious. The boys returned to the company and reported me dead. In the field report of those terrible days, I was so reported. (While being carried back, Gray had unbuttoned my clothes and found a bullet sticking about half way our of my back and found a hole in my neck.)

Toward sundown I recovered consciousness so far as to understand that I was yet in the land of suffering and living."

Realizing one's mortality while on a battlefield must have been terrifying. Perhaps Frary hoped for death to ease the pain of his terrible wounds, but somehow he survived, spending the next nine months in a military hospital.

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

"On the morning of the 6th, firing began as the first light of day showered through the trees. Soon after sunrise a charge was ordered along the whole line covered by the 5th corps. As we drove the enemy from the line they had occupied the evening before, we could see the evidence that our fire had been effective as there were dead men laying all about. Just in the rear of a large tree were six bodies fairly piled one on another.

Just before we reached the plank road, I was struck by a spent ball on the left knee, cutting through the pants and flesh, striking my knee cap, cracking it, and causing me to measure my length on the ground. On getting up, and finding that I was all together, I continued on with the line. We struck the [Orange Plank] road at an angle and wheeled slightly to the right, still driving the enemy. Men on both sides were falling, either a question of a little time when we would entirely destroy each other. Finally we came to a halt as we reached a line of their works and they opened up a battery from front and right oblique on us, at close range, with terrible effect. One shell which exploded just to my right caused three deaths and three others were wounded. Two of the dead were twin brothers by the name of Fisher.

Just after that, as I was with right knee on the ground, resting left elbow on left knee, and aiming my Enfield at Johnny standing at the right end of our ambulance, a shell exploded above and so close to my head that I heard that rending of the iron of the shell. A piece of it struck my gun on the stock, knocking it out of my hands, and hit the side of my shoe as it reached the ground. At this same instant, I felt that my whole left side was torn out. It was one awful terrible agonizing sensation as though all creation had fallen upon me, crushing and tearing my body apart, piece by piece. My first thought was that the piece of shell had gone through my body. The concussion from the shell had partly thrown me back so that when I straightened up partially, the blood gushed out of my mouth and nose as though pumped.

My captain ordered two men, W. H. Gray and Columbus W. Ford, to carry me back to the rear and stay with me. We started back, they carrying me as best they could, by holding me up under my arms. That was agonizing to me so begged them to lay me down so I could die in peace. Even then I was wondering that I could be conscious when I was torn open as I supposed I was. They sat me down by the side of the road. We could see and hear shells come tearing down the road and through the woods. I was still bleeding from nose and mouth. With others' help they boys carried me back a ways. When I was becoming faint, I begged them to lay me down, which they did. I bid them goodby as my vision dimmed, supposing that for me it was the last of earth. Thoughts of my wife and children back at home came to mind. With a mental power that God would care for them, I became unconscious. The boys returned to the company and reported me dead. In the field report of those terrible days, I was so reported. (While being carried back, Gray had unbuttoned my clothes and found a bullet sticking about half way our of my back and found a hole in my neck.)

Toward sundown I recovered consciousness so far as to understand that I was yet in the land of suffering and living."

Realizing one's mortality while on a battlefield must have been terrifying. Perhaps Frary hoped for death to ease the pain of his terrible wounds, but somehow he survived, spending the next nine months in a military hospital.

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Monday, May 5, 2014

The Battle of the Wilderness - May 5

As a boy few Civil War battles captured my imagination quite like the Battle of the Wilderness. I am not sure if it was the gory tales I read in books like The Barefoot Brigade, which painted pictures in my mind of wounded soldiers seeking medical attention only to be burned by flaming underbrush. It may have been the thoughts of a brutal battle occurring among a dense thicket of second-growth timber; each side fighting desperately for every yard of ground. I could seemingly close my eyes and in my minds-eye see the thick smoke, hear the loud cracks of thousands of muskets, and feel the earth tremble with every report of artillery.

Visiting the Wilderness battlefield years later those thoughts came back. One account that has stuck with me about the battle was penned by Captain Samuel Buck of the 13th Virginia Infantry Regiment, which was part of Gen. John Pegram's (pictured) Brigade, in Jubal Early's Division and Ewell's Corps.

Buck was a native of Warren County, Virginia, and in the spring of 1864 a 23 year old company commander. The former Winchester dry goods clerk had joined up with other eager Confederates in the spring of 1861. He was made sergeant of Company H, the "Winchester Boomerangs," and soon thereafter earned his captain bars.

As the fighting died down on the night of May 5, 1864, Buck remembered:

"We wished for night. . . . Work on our right was as heavy almost as in our front and when night did come our line stood solid, immovable. Shall that terrible night ever be erased from my memory, the terrible groans of the wounded, the mournful sound of the owl and the awful shrill shrieks of the whipporwill; the most hideous of all noise I ever heard on a battle field after the firing had ceased. The terrible loneliness is of itself sufficient, and these birds seemed to mock at our grief and laugh at the groans of the dying. Pen and words fail to describe the scene. With these exceptions, all is quiet. When I heard the familiar voice of Capt. R. N. Wilson, A.[ssistant] A.[djutant] General, calling and asking along the line for me. As I had just been on duty I felt he could not want me for regular work so concluded a scout and search for the enemy would be the call and while thus thinking had walked up the line and met him. Speaking clearly as he always did he informed me that Col. Hoffman wished me to establish a picket line as close to the enemy as I could. Not being my turn to go duty and knowing it meant staying up all night, I told Col. Wilson that he should send some one else. Admitting the justice of what I said he repeated the request saying Col. Hoffman desired it and promised to relieve me as soon as I got the line established. No escape and fully expecting to have another volley fired into me, I formed my picket line immediately in front and moved forward, stumbling over the dead and dying and they lay thicker then I ever saw them and it was hard to keep of them in the darkness.

At last I was in speaking distance of the enemy and they seemed disposed to have a truce for the night and we were rid of the usual and useless picket firing. I instructed my men not to fire and it seemed that the officer on the other side did the same as we were so close we could hear them talking plainly."

After hours of fighting how terrifying and tiring it must have been to blindly wander out beyond one's own lines to try to feel the enemy's position, knowing all the while a bullet could strike you at any minute. Sadly, Buck's experience was just one man's out of thousands of others that May 5 night.

Visiting the Wilderness battlefield years later those thoughts came back. One account that has stuck with me about the battle was penned by Captain Samuel Buck of the 13th Virginia Infantry Regiment, which was part of Gen. John Pegram's (pictured) Brigade, in Jubal Early's Division and Ewell's Corps.

Buck was a native of Warren County, Virginia, and in the spring of 1864 a 23 year old company commander. The former Winchester dry goods clerk had joined up with other eager Confederates in the spring of 1861. He was made sergeant of Company H, the "Winchester Boomerangs," and soon thereafter earned his captain bars.

As the fighting died down on the night of May 5, 1864, Buck remembered:

"We wished for night. . . . Work on our right was as heavy almost as in our front and when night did come our line stood solid, immovable. Shall that terrible night ever be erased from my memory, the terrible groans of the wounded, the mournful sound of the owl and the awful shrill shrieks of the whipporwill; the most hideous of all noise I ever heard on a battle field after the firing had ceased. The terrible loneliness is of itself sufficient, and these birds seemed to mock at our grief and laugh at the groans of the dying. Pen and words fail to describe the scene. With these exceptions, all is quiet. When I heard the familiar voice of Capt. R. N. Wilson, A.[ssistant] A.[djutant] General, calling and asking along the line for me. As I had just been on duty I felt he could not want me for regular work so concluded a scout and search for the enemy would be the call and while thus thinking had walked up the line and met him. Speaking clearly as he always did he informed me that Col. Hoffman wished me to establish a picket line as close to the enemy as I could. Not being my turn to go duty and knowing it meant staying up all night, I told Col. Wilson that he should send some one else. Admitting the justice of what I said he repeated the request saying Col. Hoffman desired it and promised to relieve me as soon as I got the line established. No escape and fully expecting to have another volley fired into me, I formed my picket line immediately in front and moved forward, stumbling over the dead and dying and they lay thicker then I ever saw them and it was hard to keep of them in the darkness.

At last I was in speaking distance of the enemy and they seemed disposed to have a truce for the night and we were rid of the usual and useless picket firing. I instructed my men not to fire and it seemed that the officer on the other side did the same as we were so close we could hear them talking plainly."

After hours of fighting how terrifying and tiring it must have been to blindly wander out beyond one's own lines to try to feel the enemy's position, knowing all the while a bullet could strike you at any minute. Sadly, Buck's experience was just one man's out of thousands of others that May 5 night.

Saturday, May 3, 2014

This Week 150 Years Ago

As if the bloodletting battles of 1862 and 1863 were not bad enough, the sustained intensity of combat in the Civil War was about to increase drastically this week 150 years ago.

General Ulysses S. Grant, now ultimately directing the Army of the Potomac, transitioned that force into a method of warfare that it had not yet experienced. The Battle of the Wilderness (May 5-6), which was fought largely on what was arguably the Army of Northern Virginia's field of greatest success (Chancellorsville, May 1863) and most costly loss (the wounding and eventual death of Gen. Thomas J. Jackson), witnessed a bulldog tenacity offensive from the Yankees and a stubborn defense from the Confederates among a tangled mess of timber. When that battle ended the smoke only cleared for a few hours before the belligerents were at it again, this time at Spotsylvania Courthouse (May 7-12). A ferocity of combat none of the participants would forget tested the will power of all involved as desperate hand-to-hand fights broke out again and again over those small few small acres.

Fighting in such close confines and in such a sustained manner introduced a new age of earthwork construction and way of fighting. After Spotsylvania the fighting only continued at intense engagements around the North Anna River and then into June at Cold Harbor. The thwarted attack at Cold Harbor led Grant finally to Petersburg, and the fighting raged there in June, July and August.

Over in the Western Theater, with Grant gone east, General William T. Sherman battled Confederate general Joseph E. Johnston in northern Georgia. Like Grant, Sherman pushed and flanked with a new found intensity. Johnston's best chances for victory in the North Georgia mountains were lost opportunities as he retreated, entrenched, fought, retreated, entrenched, and fought on through the foothills.

A series of battles at Kennesaw Mountain slowed Sherman's progress somewhat in June, but by July, the Confederates were backed up to Atlanta. A change in command by President Jefferson Davis, who put his trust in the wounded warrior Gen. John Bell Hood. The switch in generals brought out a fighter who literally bled his Army of Tennessee in severe battles around the vital rail-hub city in July and August. Finally, Atlanta capitulated in early September.

Long gone were the days of fighting an intense battle and then each side going back to their corners to lick their wounds and rethink their strategy. With Grant now setting the strategy the story in 1864 was sustained fighting - a literal battle of attrition - which brought an unprecedented amount of killed, wounded (both physically and mentally), and captured soldiers. There would not be a more terrible year of that terrible war than 1864; and it all began this week 150 years ago.

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.